Alexander the Great: an ancient horse whisperer

How do you tame a wild horse?

13 January 2023How do you tame a wild horse?

13 January 2023Blog series Medieval manuscripts blog

Author Giulia Gilmore

The average medieval reader would have been familiar with horses both on the page and in real life. Horses have served humans throughout history, particularly for warfare or transportation.

They are also faithful companions to many heroes in ancient and medieval literature. Taming a feral horse, on the other hand, is no easy feat. Only the most skilled warrior would be capable of undertaking such a difficult task. According to legend, this was none other than Alexander the Great.

Alexander and his horse, Bucephalus, in Le livre et la vraye hystoire du bon roy Alixandre (Paris, c. 1420–c. 1425): Royal MS 20 B XX, f. 12r.

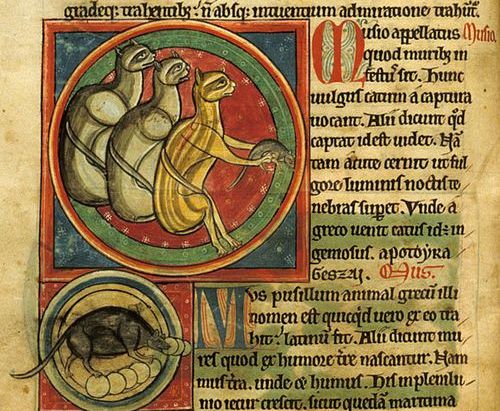

Alexander the Great’s horse is one of the most famous equine figures in ancient and medieval literature. His name ‘Bucephalus’ derives from the Greek ‘Βουκεφάλας’ meaning ‘ox-head’. He was no ordinary horse, as his name indicates, for he is often depicted in medieval versions of Alexander’s legends as an untamed hybrid with three horns on his head. He was also notorious for eating human beings.

When Alexander was a teenager, his father, King Philip of Macedonia, enclosed Bucephalus in a dungeon for safekeeping, but he would send traitors to the horse’s enclosure to be devoured as punishment. Illuminations from some of our manuscripts portray Bucephalus in a cage or chained with shackles. Later, King Philip heard a prophecy that predicted that only the one who could tame and mount the wild horse would be the future king.

Alexander taming Bucephalus, in Roman d'Alexandre in prose (Southern Netherlands, c. 1290–1300): Harley MS 4979, f. 15r.

According to an earlier version of the episode in Plutarch’s Life of Alexander, no one was able to mount the horse or tame him, until Alexander noticed that the horse became distressed from the movements of his own shadow. To calm the animal, Alexander turned the horse towards the Sun, so that his shadow no longer frightened him. At last, Alexander was able to mount Bucephalus and claimed him as his own charger, ready for his destined conquests.

Alexander and Bucephalus, in the Talbot Shrewsbury Book (Rouen, c.1445): Royal MS 15 E VI, f. 7r.

In some medieval texts, such as Thomas of Kent’s Le roman de toute chevalerie, Bucephalus’s ferocity was used to Alexander’s advantage in battle. The horse is described as tearing violently through the enemy cavalry, since Bucephalus often preferred human flesh over grass.

In an earlier version of the Alexander legends, known as the Greek Alexander Romance, Bucephalus outlived Alexander, and wept for his master on his deathbed after Alexander was poisoned during his coronation feast at Babylon. On the subject of grieving horses, Isidore of Seville, a 7th-century scholar, claimed that horses ‘shed tears when their master dies or is killed, for only the horse weeps and feels grief over humans’ (Etymologies, book 12, 1:41: translated in The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, ed. Stephen A. Barney et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 249). Perhaps Isidore had heard of the loyalty and grief shown by Bucephalus’s towards his master, Alexander the Great, or that of other loyal horses throughout history and literature.

In later medieval versions of the story, Bucephalus is killed prematurely in battle by Alexander’s arch-enemy, King Porrus, before Alexander’s coronation at Babylon. In one manuscript illuminated in 15th-century Paris (Royal MS 20 B XX), this occurs soon after Alexander had successfully unhorsed Porrus during a joust.

Tragically, for Bucephalus, Porrus got his own back when he managed to kill Alexander’s beloved horse in battle. Alexander, distraught at the loss of his loyal companion, buried Bucephalus with his soldiers by his side.

Alexander unhorsing Porrus: Royal MS 20 B XX, f. 53r.

The burial of Bucephalus: Royal MS 20 B XX, f. 81r.

In honour of his heroic horse, Alexander dedicated a city in his name, so that the memory of Bucephalus was not forgotten. And so, from a ferocious caged beast to a most loyal royal companion, Bucephalus lives on in the legends of Alexander that we continue to read today.

Alexander building a city as a memorial to his horse, Bucephalus: Royal MS 20 B XX, f. 82r.

This blog is part of our Medieval manuscripts series, exploring the British Library's world-class collections of manuscripts – including papyri, medieval illuminated manuscripts and early modern state papers.

Our Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts series promotes the work of our curators, who are responsible for these items and thousands more.

Discover medieval historical and literary manuscripts, charters and seals, and early modern manuscripts, from Homer to the Codex Sinaiticus, from Beowulf to Chaucer, and from Magna Carta to the papers of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I.

You can access millions of collection items for free. Including books, newspapers, maps, sound recordings, photographs, patents and stamps.