Keep taking the (wax) tablets

Besides the various types of pens, quills and pencils, one of the earliest and most popular writing tools, used for more than five millennia, is the stylus.

8 May 2019Besides the various types of pens, quills and pencils, one of the earliest and most popular writing tools, used for more than five millennia, is the stylus.

8 May 2019Blog series Medieval manuscripts blog

Author Peter Toth (British Library) and Alan E. Cole (Hon Consultant, Museum of Writing Research Collection, University of London)

Besides the various types of pens, quills and pencils, one of the earliest and most popular writing tools, used for more than five millennia, is the stylus. The name comes from the Latin word stilus, meaning 'a stake'. It refers to a small, pointed instrument made of metal, wood or bone, used by the Romans for writing upon wax tablets.

-burney-ms-19,-f.-1v.png?auto=format)

Image of a writing desk from a Byzantine gospel book (Constantinople, 12th century): Burney MS 19, f. 1v.

-add-ms-54180,-f.-5v.png?auto=format)

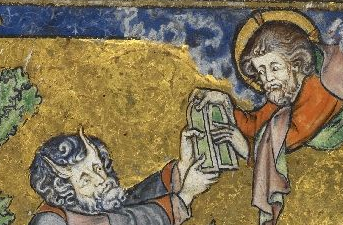

Tablets of the Ten Commandments in Laurent d'Orléans, La Somme le Roi (Paris, c. 1295): Add MS 54180, f. 5v.

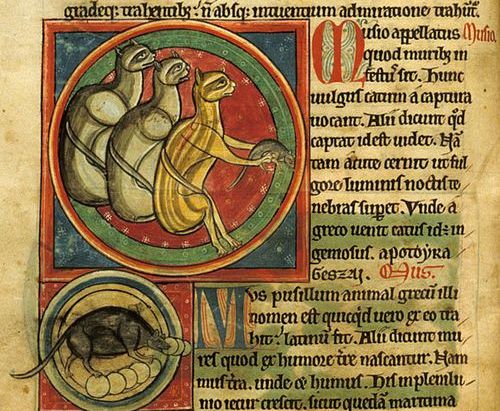

The term 'tablet' can cover a variety of writing materials. One perhaps thinks of a stone with writing carved onto it, such as the two tablets of the Ten Commandments said to have been carved by God. However, it was not only iconic pieces of inscribed stones that were employed in this way in Antiquity, since tablets made of wood or wax were more commonly in use.

-add-ms-49598,-f.-92v.png?auto=format)

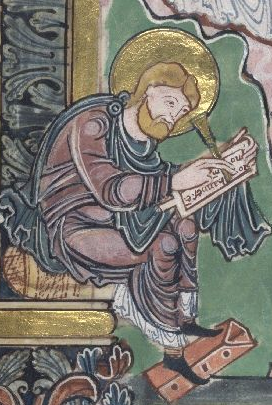

Zachariah writing on a tablet in the Benedictional of Æthelwold (England, 963–984): Add MS 49598, f. 92v.

The earliest surviving wooden writing tablet was recovered from a 3,500-year-old shipwreck near Kaş, in modern Turkey, in 1986. They were not in common use until about 715BC with the Neo-Assyrians in Mesopotamia. In the 7th century BC, the Greeks set up a community in Egypt from where the next oldest tablet was found, although it does not appear that the Egyptians themselves actually used such tablets. They became more common in the Roman Empire, surviving in considerable quantities from Egypt to Britain. Wooden tablets would have been written on with pen and ink, similar to a sheet of papyrus or a page of parchment.

-add-ms-37533-(4).png?auto=format)

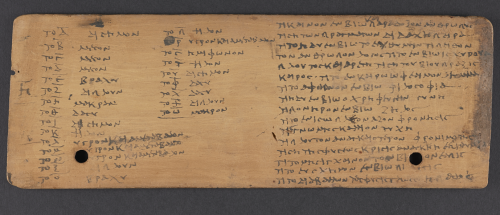

The alphabet in a teacher’s notebook (Egypt, 2nd century AD): Add MS 37533 (4).

Documents on wooden tablets were usually ephemeral in nature. Pieces written for or at school are the most common survivors, such as teachers' notebooks, children's homework or private letters (such as the famous Vindolanda tablets excavated from Hadrian’s Wall).

-add-ms-33270.png?auto=format)

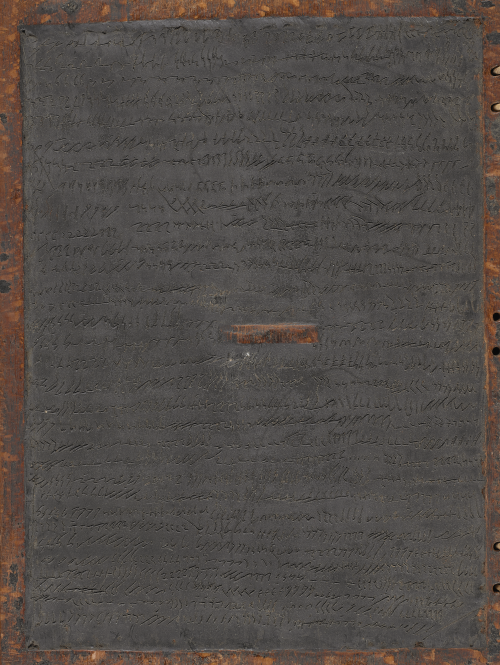

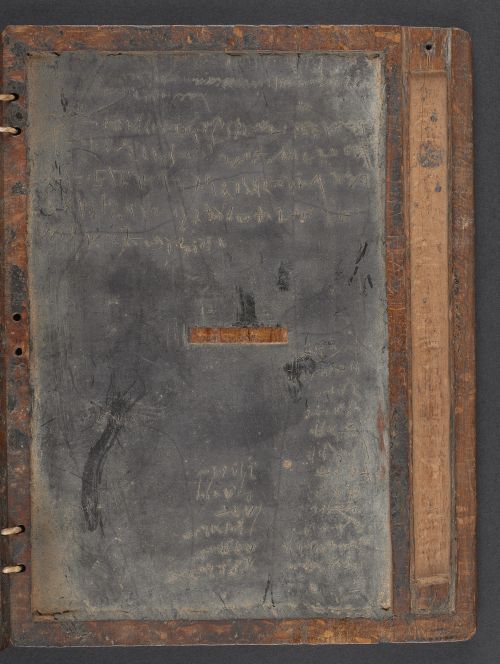

A student’s Greek shorthand notes in wax (Egypt, 2nd century): Add MS 33270

The earliest documented use of wax tablets dates from Italy in the 7th century BC. The Etruscans used them not only for writing but also as amulets. Their wider use started with the Greeks, who were great beekeepers and had plenty of beeswax at their disposal. For a short period, there was a ban on the export of papyrus from Egypt, meaning that wax tablets were in regular use. Styluses would have been employed to scratch letters in the smooth wax.

Most tablets were made from the sandarac tree (Tetraclinis articulata, a member of the cypress family) or from boxwood. A flat, rectangular block would have been hollowed out and filled with wax, often black or natural or with a sooty coating, so that the lighter colour showed through when written on.

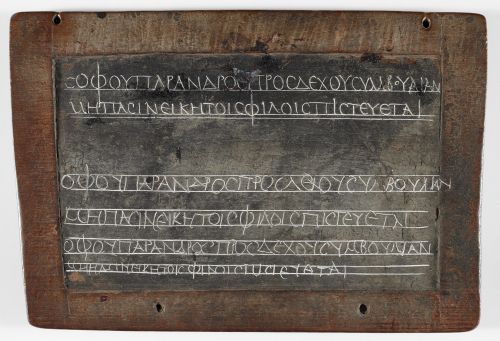

A Greek writing exercise from Egypt, 2nd century AD: Add MS 34186.

Wax tablets were used in similar contexts as their wooden counterparts. Cheap and easy to re-use, wax tablets were ideal for teaching children to write. The item shown here, approximately the size of a modern iPad, is a homework-book used about 1,800 years ago at a Greek school in Egypt. The teacher wrote out two lines of a maxim on the top of the tablet, which were to be copied out by the child at home. The pupil tried their best but made several mistakes: the first letter in the first line ('C') was missed out twice, the last letter of the line ran over the margin, and the last line became compressed.

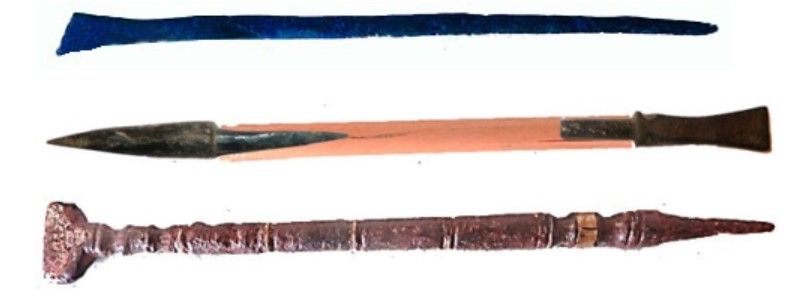

(1) A Roman bronze stylus; (2) a Roman stylus with a separate greenstone writing point and bronze eraser; (3) a Roman bronze stylus with five gold bands (photos: Museum of Writing Research Collection) © Museum of Writing Research Collection, University of London

The sharp end of an iron stylus was used to write, while the blunt end was heated over a flame and used to erase mistakes or smooth the wax for reuse. The styluses were often stored with the tablets themselves: the last part of a set of tablets often contained a little groove in which to store the stylus.

-add-ms-33270-(9).jpg?auto=format)

The last part of a set of bound wax tablets with a groove to store the stylus (Egypt, 2nd century): Add MS 33270 (9).

How would words be erased from a wax tablet? Alan Cole, the consultant of the Museum of Writing Research Collection, has experimented as follows: 'I used original, Roman metal styli and an original Roman lamp. I held the stylus in my thumb and forefinger about a centimetre and a quarter from the flat end and held it in the tip of the flame until I began to feel the warmth. It was then at the optimum temperature to erase a few characters. This worked for iron and bronze. Not advisable for silver, gold, wood or bone! To erase a whole tablet of characters, hold the tablet upside-down, just above the tip of the flame, and gently move the wax over it until the surface is about at melting point and then remove it from the flame and with the tablet wax side up either move the tablet in a slight see-saw movement or gently go over the surface with a warmed stylus. Personally, I use a blow-torch!'

This blog is part of our Medieval manuscripts series, exploring the British Library's world-class collections of manuscripts – including papyri, medieval illuminated manuscripts and early modern state papers.

Our Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts series promotes the work of our curators, who are responsible for these items and thousands more.

Discover medieval historical and literary manuscripts, charters and seals, and early modern manuscripts, from Homer to the Codex Sinaiticus, from Beowulf to Chaucer, and from Magna Carta to the papers of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I.

You can access millions of collection items for free. Including books, newspapers, maps, sound recordings, photographs, patents and stamps.