King Arthur: fable, fact and fiction

King Arthur is one of our most popular heroes but what do we actually know about him?

1 September 2019King Arthur is one of our most popular heroes but what do we actually know about him?

1 September 2019Blog Medieval Manuscripts blog

Author Chantry Westwell, historian and author.

King Arthur is one of our most popular heroes: noble yet flawed, a great leader (but perhaps not such a great judge of character), a brave soldier who died fighting for a noble yet hopeless cause. There are tantalising fragments of evidence that the legendary figure may be based on a real king who fought to defend Britain against Anglo-Saxon invaders around the 5th-6th centuries. But was he a Celt, a Roman, a Briton or an Anglo-Saxon, and did he really take on the Anglo-Saxons?

If King Arthur existed at all, we will probably never know the truth about what he was really like. The sources that describe him were written centuries later, when his life had already turned to legend. But what endures about King Arthur are the many stories that people crafted about him thoughout the Middle Ages. Here we explore some of the manuscripts that contributed to the growth of Arthur’s legend.

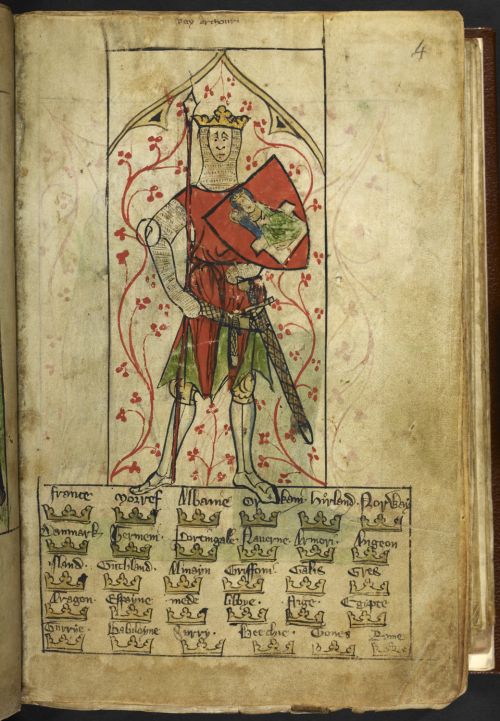

Miniature of King Arthur, holding a spear and a shield emblazoned with the Virgin and Child from a collection including Langtoft’s chronicles: Northern England, c. 1307 – 1327, Royal MS 20 a ii, f. 4r

Two of the earliest accounts of King Arthur were by William of Malmesbury (b. c. 1090, d. c. 1142) and Geoffrey of Monmouth (d. 1154/55), Anglo-Norman clerics who wrote historical chronicles in Latin in the first half of the 12th century. Geoffrey’s History of the Kings of Britain portrayed Arthur at the outset as a brave and fearsome young warrior, who dons his battle regalia (as in the image above, from Royal MS 20 a ii, which is of a later date) and defeats multiple enemies single-handedly. He established Arthur’s reputation as a powerful Christian monarch who embodies the qualities of generosity and culture, qualities demonstrated in the earliest surviving image of Arthur in a manuscript, where he is shown as a tall, venerable figure with a beard and a long robe (BnF lat. 8501A, below).

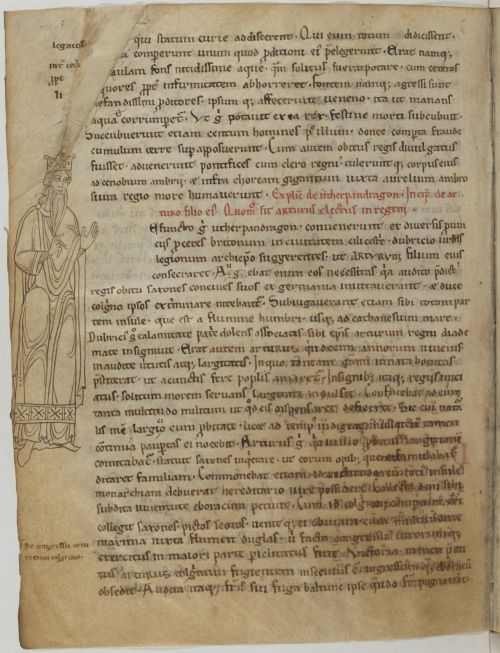

A portrait of Arthur at the beginning of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae: Mont Saint-Michel, second half of the 12th century, BnF, lat. 8501A, f. 108v BnF, lat. 8501A, f. 108v

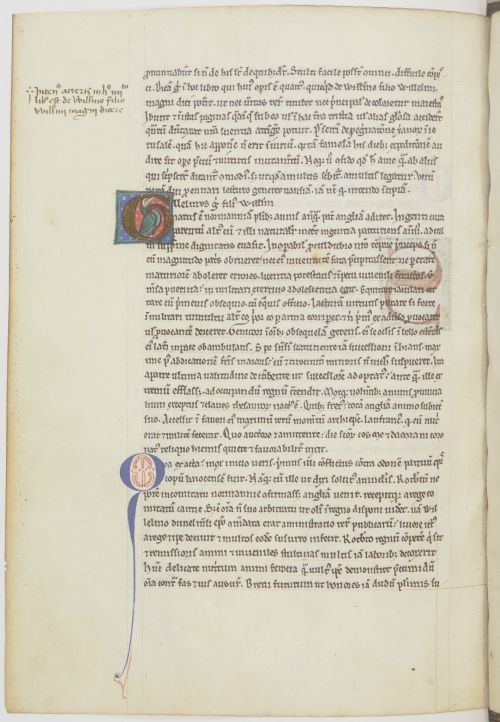

As many medieval chroniclers did, Geoffrey introduced elements from legend. For him Arthur belonged to an idealised past, peopled with dragons and the chivalrous knights and virtuous maidens of the magnificent Camelot. In contrast, William of Malmesbury was critical of the ‘fond fables which the Britons were wont to tell’, and for him Arthur was merely a ‘praiseworthy’ and ‘warlike’ leader. His Deeds of the English Kings begins with the Anglo-Saxon invasions in 449 and tells of Arthur’s single-handed defeat of 900 invaders. This copy of his work from Saint Alban’s Abbey, is decorated with initials containing a dragon, a lion and other creatures, perhaps referencing Arthur’s magical associations (BnF lat. 6047, below).

An initial containing a bird, in William of Malmesbury Gesta Regum Anglorum: St Alban’s abbey, last quarter of the 12th century, BnF, lat. 6047, f. 93v

Later in the 12th century, authors on both sides of the channel, including Wace, Layamon and most notably Chretien de Troyes, adapted the Arthurian legend, embellishing it with tales of Arthur’s early education by Merlin, his chivalrous exploits with Lancelot, Gawain and the knights of the Round Table, and his doomed romance with Guinevere.

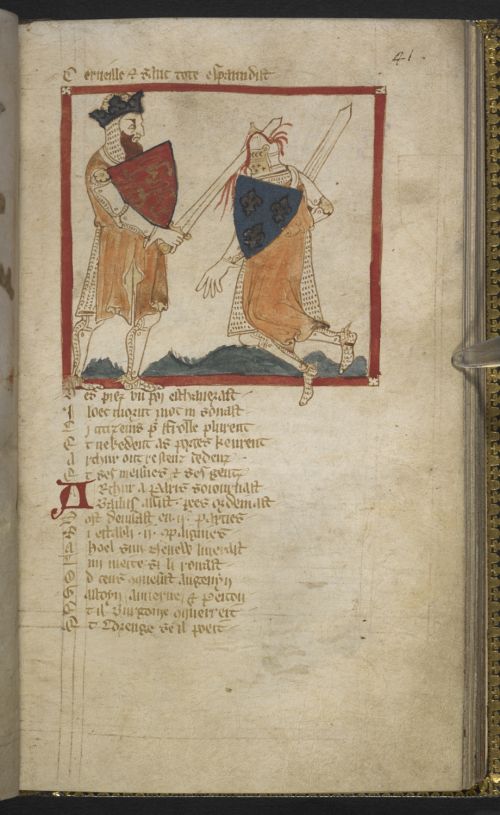

The illustrations in this 14th-century English manuscript of Wace’s Roman de brut, a history of England from the time of Brutus, depict Arthur as a warrior king (Egerton MS 3028, below). Here he is shown leading the conquest of Gaul. Red-bearded and in full armour, with a fierce grimace on his face, he splits in two the head of Frollo, tribune of Gaul, with his sword.

Arthur killing Frollo, Roman de Brut: England, 2nd quarter of the 14th century, Egerton MS 3028, f. 41r.

Wace introduced the Round Table in his Roman de Brut, completed in 1155, and his words ‘Arthur .. bore himself so rich and noble…[and the] Round Table was ordained ….At this table sat Britons, Frenchmen, Normans, Angevins, Flemings, Burgundians and Loherins’. Here Wace brings Europe’s leaders to his table, portraying Arthur as not only an inspiring and fair ruler, but an international statesman of note.

Perceval is brought to Arthur at the Round Table (the rubric specifies ‘table roonde’ the artist has depicted the table as long), from the Lancelot-Grail: Northern France , 1316, Add MS 10293, f. 376r

But there is a dark side to Arthur in de Boron’s Roman du Graal, as illustrated in a manuscript of this work (Add MS 38117, below). Wanting to rid his kingdom of the evil Mordred, his son conceived by incest, Arthur finds all the children born on the same day and sets them adrift in a boat, sending them to a certain death by drowning.

King Arthur setting infants adrift in a boat from Robert de Boron, Suite de Merlin: Northern France (Arras?), 1310, Add MS 38117, f. 97v

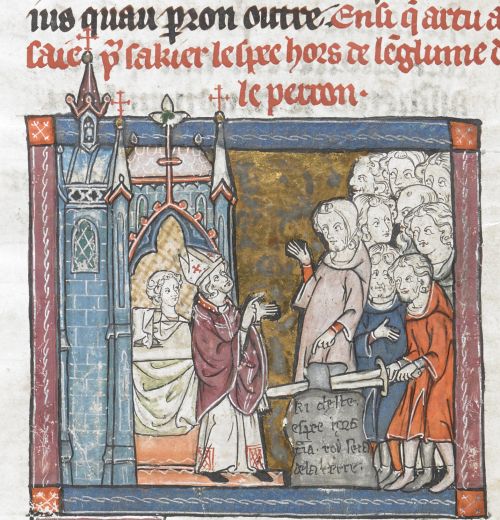

All the stories about King Arthur and his court were brought together in the early 13th century in the monumental prose version known as the Vulgate Cycle. It was a medieval literary phenomenon, surviving in around eighty manuscripts from the 13th to the 15th century. This illuminated manuscript of the work shows Arthur as a humble young squire, drawing the sword from the stone (Add MS 10292, below).

Arthur draws the sword from the stone, from the Lancelot-Grail Vulgate Cycle: Northern France (Saint-Omer or Tournai), c. 1316, Add MS 10292, f. 99r

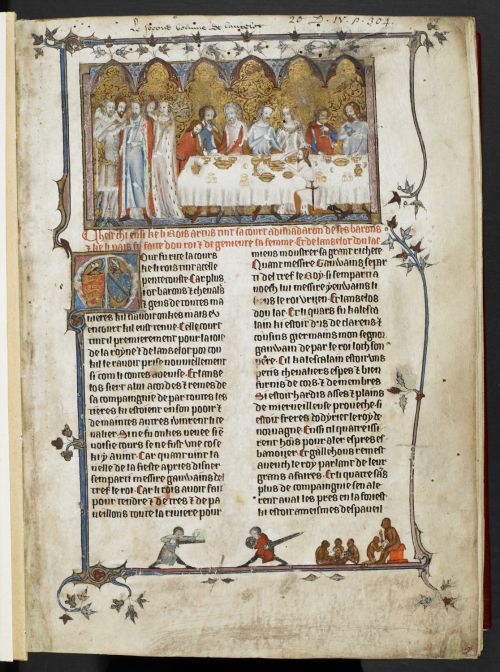

Arthur, Lancelot and Guinevere at Camelot in Lancelot du Lac England, S. (Pleshey castle): c. 1360- c. 1380, Royal 20 D IV, f. 1r

The doomed love triangle between Arthur, Guinevere and Lancelot leads to the king’s ultimate downfall and he is seen as gullible, though not blameless in the situation that develops. In the image above, set at Camelot, he is the gracious and dutiful king (on the right), seated beside Guinevere, their arms entwined, and in another episode from the story (on the left), Lancelot and Guinevere conduct their intrigues behind his back (Royal MS 20 D IV).

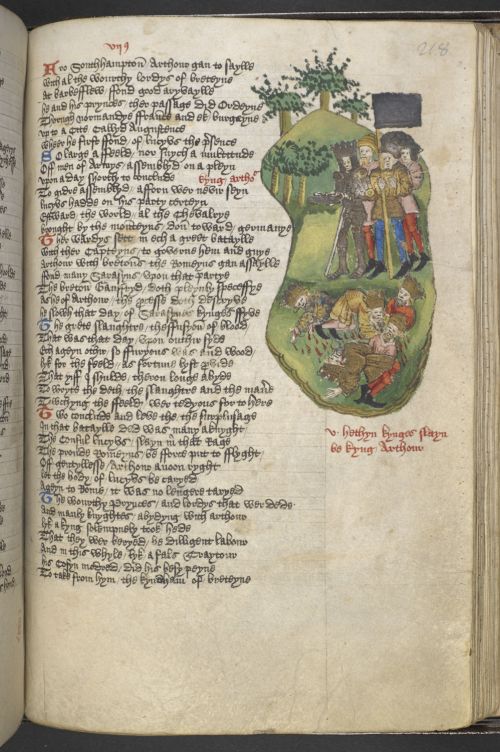

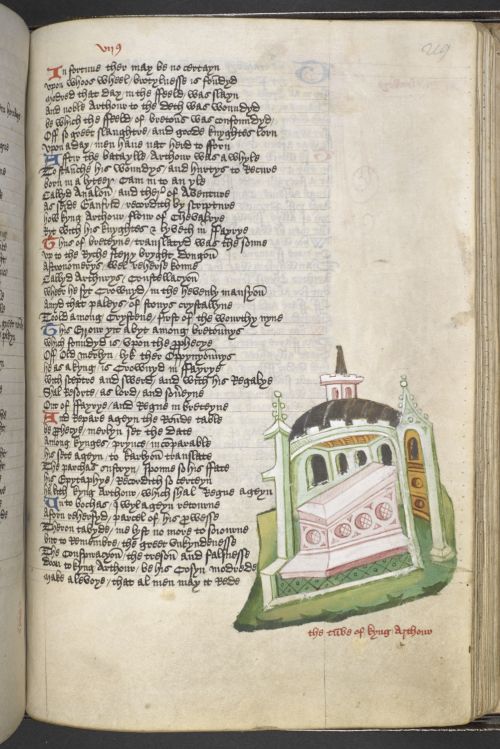

Lydgate’s 15th-century work, The Fall of Princes, based on a work by Boccaccio, includes Arthur as an example of how the mighty fall. This manuscript shows Arthur, victorious, slaughtering his enemies on one page, and on the next is an image of his tomb at Avalon (Harley MS 1766, below).

King Arthur slaying heathens, from The Fall of Princes: South-east England, 1450-1460, Harley MS 1766, f. 218r

King Arthur's tomb, from The Fall of Princes: South-east England, 1450-1460, Harley MS 1766, f. 219r

Although we will never know who Arthur really was, the adaptability of his legend allowed him to remain relevant throughout the Middle Ages and to continue to capture people’s imagination to this day.

This blog is part of our Medieval manuscripts series, exploring the British Library's world-class collections of manuscripts – including papyri, medieval illuminated manuscripts and early modern state papers.

Our Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts series promotes the work of our curators, who are responsible for these items and thousands more.

Discover medieval historical and literary manuscripts, charters and seals, and early modern manuscripts, from Homer to the Codex Sinaiticus, from Beowulf to Chaucer, and from Magna Carta to the papers of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I.

You can access millions of collection items for free. Including books, newspapers, maps, sound recordings, photographs, patents and stamps.