Lolcats of the Middle Ages

Let's trace the internet's obsession with cat memes to the Middle Ages...

21 January 2013Let's trace the internet's obsession with cat memes to the Middle Ages...

21 January 2013Blog series Medieval manuscripts

Author Nicole Eddy

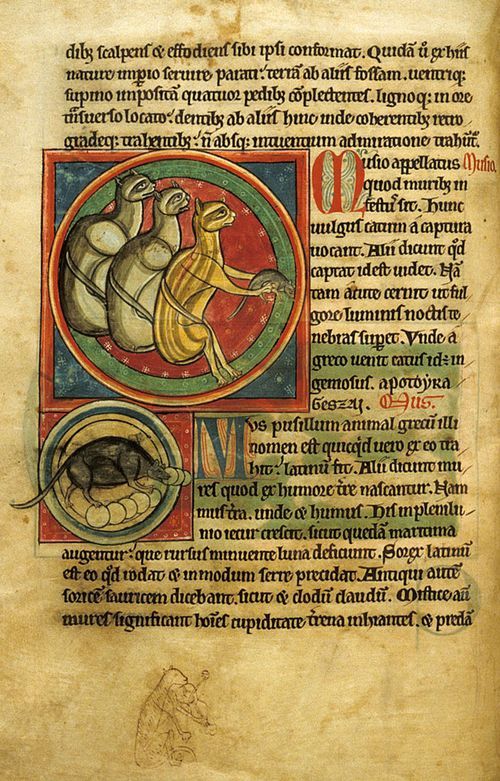

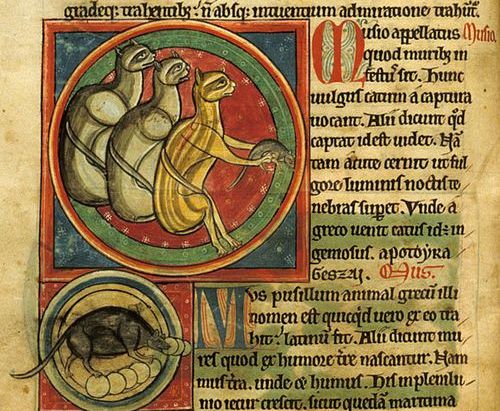

The internet is considered by many to be a delivery-system for pictures of cats, and it should be no surprise, therefore, to learn the identity of today's bestiary animal. As it is today, the enmity between the cat and the mouse was well-established in the medieval imagination. Isidore of Seville even proposed an (incorrect) etymology for 'cat' (Latin catus) in the word captura, a form of a word meaning 'catch,' suggesting that this referred to the cat's catching of mice. Or, he continues, 'capture' may refer to cats 'catching' large amounts of light with their eyes, to see in the dark.

Either way, cats were often shown in manuscript illumination with mice they have caught, and below, we can even see a Tom-and-Jerry style depiction of a mouse caught by a cat, caught in turn by a dog. No word on the current disposition of the house that Jack built.

Detail of miniatures of cats catching mice, mice stealing wafers, and (below), an ancestor of Keyboard Cat: a later marginal doodle of a cat playing a stringed instrument,

Detail of an historiated initial 'O' (vi) of a dog catching a cat catching mice; from Gregory the Great, Moralia in Job, Germany (Arnstein), 2nd half of the 12th century, Harley MS 3053, f. 56v.

The mouse was not always the loser in these exchanges, however, especially in the imaginative realm of the marginal grotesque. Sometimes you eat the mouse, the cat may have philosophized, and sometimes the mouse eats you. The relationship between mice and cats, and the prospect of an organized mouse insurrection against the oppressor, was actively explored as a metaphor for human society.

The 14th-century poet William Langland adapted the familiar tale of mice belling the cat as a comment on relations between the powerful regent John of Gaunt and the Commons, with a council of mice deciding that, in addition to the obvious difficulty of finding a volunteer for the delicate task, there was some question as to whether the outcome would even be desirable.

While the mice remain inconspicuous, one council member advises, the cat 'coveiteth noght oure caroyne' ('does not desire our flesh'), but should they draw the cat's attention, then he would pursue them even more cruelly – a pointed satire indeed, in the political environment just before the 1381 uprising.

Detail of a miniature of mice laying siege to a castle defended by a cat; from a Book of Hours, England (London), c. 1320-c. 1330, Harley MS 6563, f. 72r.

Miniature of a nun spinning thread, as her pet cat plays with the spindle; from the Maastricht Hours, the Netherlands (Liège), Stowe MS 17, f. 34r; for more on the Maastricht Hours.

Cats could be companion animals as well. One guidebook on appropriate behaviour and conduct for anchoresses (female hermits), famously advises that, while the anchoress was forbidden most luxuries, she was allowed a pet cat. And Alexander the Great, whose fictional explorations of the natural world were retold throughout the Middle Ages, included a cat, along with the cock and the dog, as his companions in a proto-submarine. Here, the animal was not merely a pet, but a natural rebreather, purifying the air so Alexander would not stifle in the enclosed space.

The dog was more unfortunate, chosen as an emergency escape mechanism: water, medieval readers were assured, would expell the impurity of a dog's dead carcasse. If Alexander encountered danger, he had only to kill the dog, which would be expelled to the surface, bringing Alexander with it. As for the cock – everyone knows how valuable they are for telling time with their crows, a useful function underwater, out of sight of the sky.

Detail of Alexander exploring the ocean in a glass barrel.

Above we can see a detail of a miniature of Alexander exploring the ocean in a glass barrel, accompanied by a cat and a cock; in this version of the story, his unfaithful wife tries to murder him by cutting the cord connecting him with the ship, and it is by killing the cat (not a dog) that he is able to rise to the surface; from Le livre et le vraye hystoire du bon roy Alixandre, France (Paris), c. 1420, Royal MS 20 B XX, f. 77v.

On the subject of cats, you may also like to see Kathleen Walker-Meikle's book, Medieval Cats, published by British Library Publications (£10, ISBN 9780712358187).

This blog is part of our Medieval manuscripts series, exploring the British Library's world-class collections of manuscripts – including papyri, medieval illuminated manuscripts and early modern state papers.

Our Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts series promotes the work of our curators, who are responsible for these items and thousands more.

Discover medieval historical and literary manuscripts, charters and seals, and early modern manuscripts, from Homer to the Codex Sinaiticus, from Beowulf to Chaucer, and from Magna Carta to the papers of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I.

You can access millions of collection items for free. Including books, newspapers, maps, sound recordings, photographs, patents and stamps.