Love spells in the Greek Magical Papyri

As it’s nearly Valentine’s Day, we have collected some ‘charming’ love spells preserved in the Greek magical papyri of the British Library.

13 February 2021As it’s nearly Valentine’s Day, we have collected some ‘charming’ love spells preserved in the Greek magical papyri of the British Library.

13 February 2021Blog series Medeival manuscripts blog

Author Dr Federica Micucci, Cataloguer and researcher of Greek Papyri, British Library

We have collected some ‘charming’ love spells preserved in the Greek magical papyri of the British Library. Such spells were believed to rouse love and passion, but more worryingly they were also intended to bind and attract the loved one to the user. Some spells even went so far as to cause suffering to the victim, which was to end after the lovers were united. Most of the spells presented below are preserved in Papyrus 121, a magical handbook presumably from 4th-century Egypt, originally a roll over two metres long, containing spells for various purposes, from healing and binding to obtaining protection and success.

Love spells often have titles that define their nature in more detail. One of the most frequent types are the love spells ‘that lead’, named agōgē and agōgimon in Ancient Greek (from the verb agō, ‘to lead’). This type of spell had the aim of bringing the victim to the person performing the magic. One of these spells instructs the user to take a seashell, write holy names with the blood of a black donkey, and recite a formula to attract the victim. The user should select the time to perform the ritual very carefully, as the spell had immediate effect.

,-col.-6.jpg?auto=format)

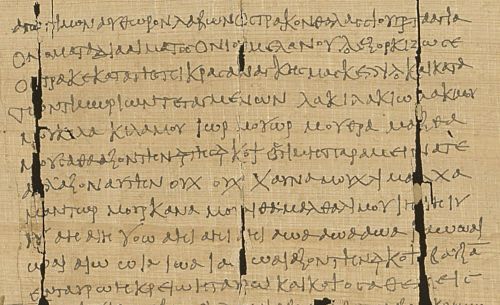

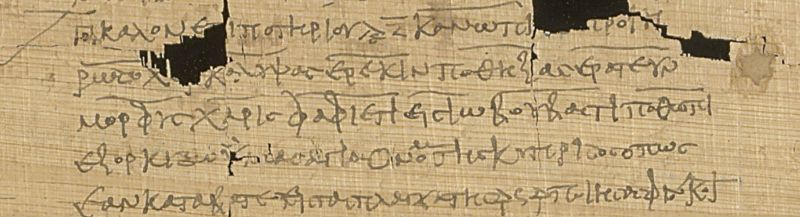

‘Love charm which acts in the same hour’: Papyrus 121(2), col. 6

Magical words (voces magicae) recur constantly in the magical papyri. These are unintelligible sequences of words or syllables thought to have magical power. This spell, believed to obtain the eternal love of a woman on the spot by invoking the god Iabo, displays some magical words at the end.

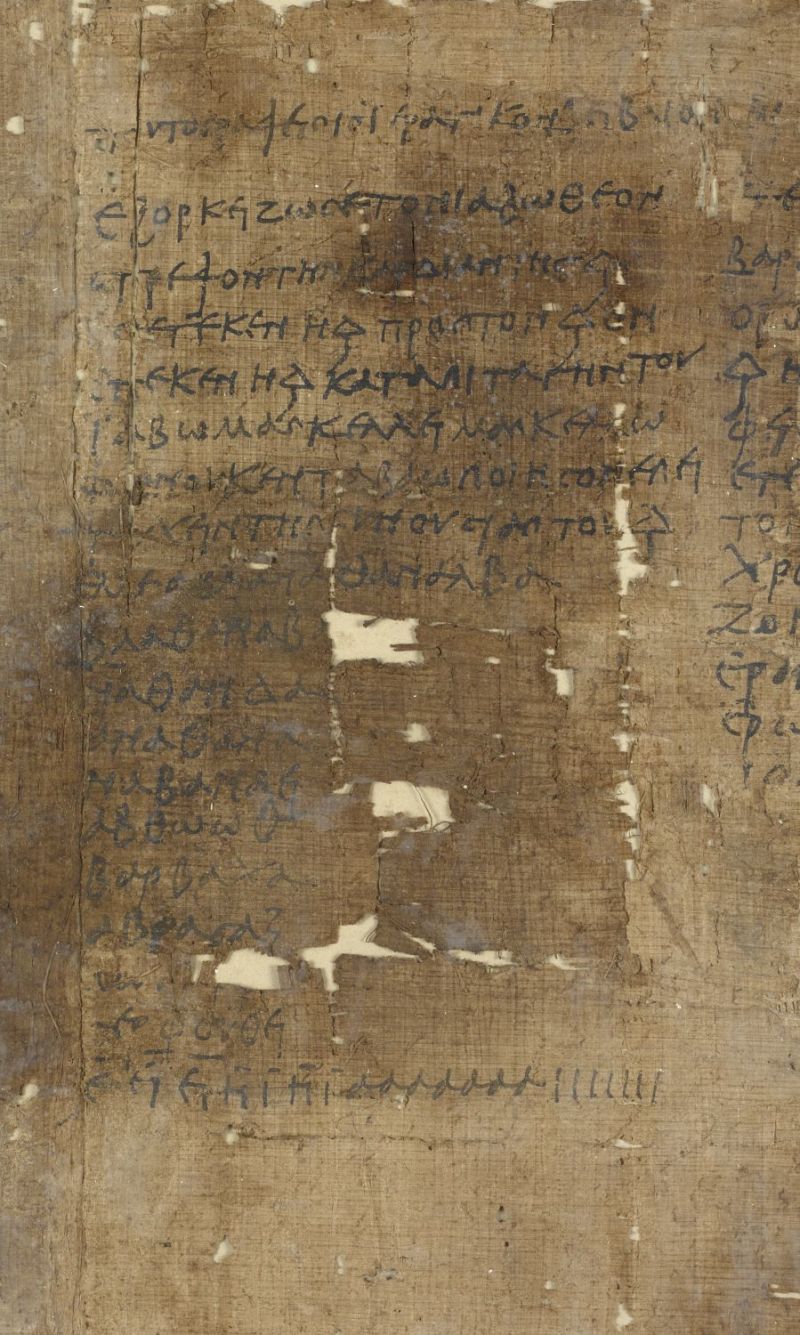

A love spell to secure the eternal love of a woman: Papyrus 148

Magical signs, known as charaktēres, were another powerful tool. These symbols often had the shape of asterisks or lines ending in small circles. The following love spell makes use of such signs. The spell is described as an ‘excellent love charm’, literally ‘potion’ (philtron). It explains that a tin lamella should be engraved with some magical signs and names, rolled up with some magical material (perhaps a lock of hair or a piece of clothing) and thrown into the sea. The practitioner should also remember to use a copper nail from a wrecked ship for writing!

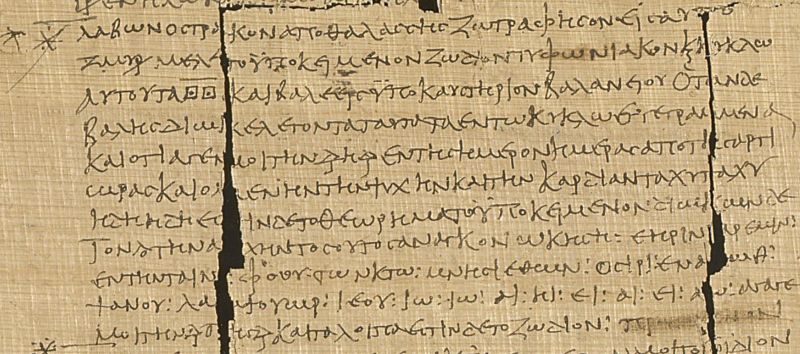

,-column-10.jpg?auto=format)

An ‘excellent love charm’, reminding the user to ‘write with a copper nail from a shipwrecked vessel’: Papyrus 121(2), column 10

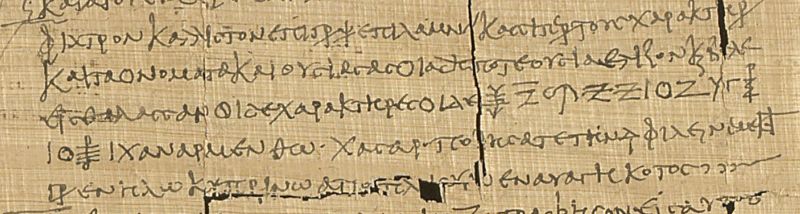

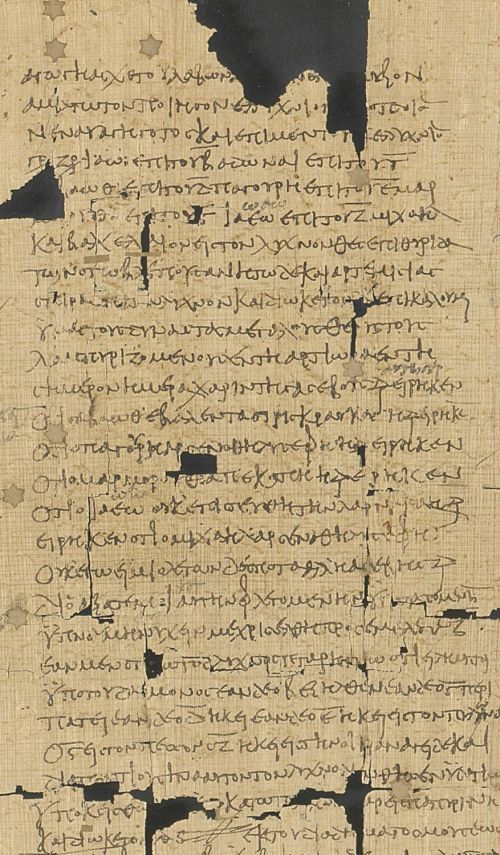

Invoking deities for help is another common feature of love spells. A special invocation to Selene, the Moon, is contained in the following spell. Addressing Selene as the ‘mistress of the entire world’, the user was instructed to make offerings to her by moulding a mixture of clay, sulphur, and blood of a dappled goat into a figurine of the goddess, and by consecrating a shrine made of olive wood, which should never face the sun. As a result, Selene would send a holy angel, who would drag the victim by their feet and hair to the user. The victims would be fearful and sleepless because of their love for the individual performing the magic. Success is guaranteed, as the ‘power of the spell is strong’, according to the papyrus.

verso,-columns-8-9-(numbered-25-6).jpg?auto=format)

Portions of a lunar spell to bind and attract the victim and obtain their eternal love: Papyrus 121(2)verso, columns 8-9 (numbered 25-6)

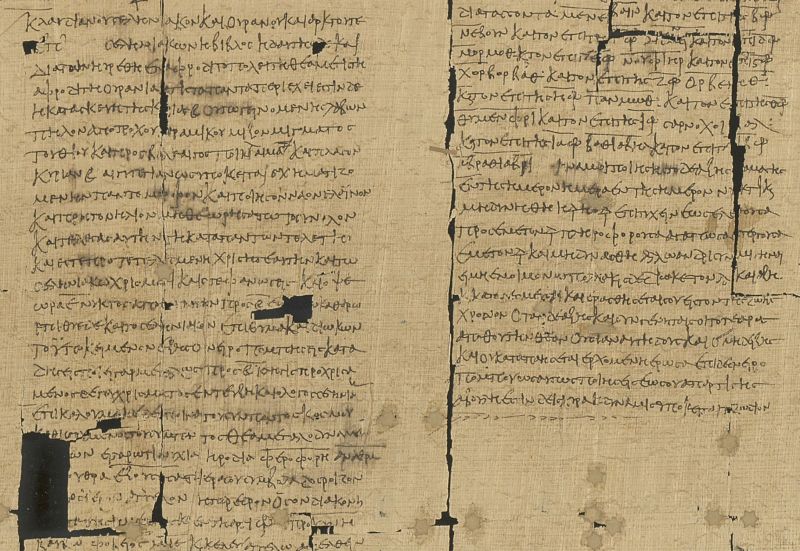

Among the objects featuring in magical rituals are also those of daily use. The following spell is ‘a good drinking cup’ spell: over a cup, the user ought to repeat magical words seven times. These were believed to be ‘holy names of Cypris’, that is, Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Users of the spell hoped that the loved ones’ heart could be reached, and their love would be returned.

,-column-8.jpg?auto=format)

A good cup spell, with a formula to be recited over a cup: Papyrus 121(2), column 8.

Spells may have been accompanied by drawings to serve as a model for performing the ritual. For example, a picture is mentioned in the following spell, although the papyrus itself does not preserve it:

‘Take a shell from the sea and draw on it with myrrh ink the figure of Typhon given below, and in a circle write his names, and throw it into the heating of a bath. But when you throw it, keep reciting these words engraved in a circle and attract to me her, NN, whom NN bore, on this very day from this very hour on, with her soul and heart aflame, quickly, quickly; immediately, immediately’.

-column-10.jpg?auto=format)

Instructions for attracting the victim straightaway: Papyrus 121(2) column 10.

This ‘fetching’ spell (agōgē) was believed to work with ‘unmanageable’ targets. The names of seven ‘great gods’ should be written with myrrh on seven wicks of a lamp, which ought not to be red. The lamp was lit and had wormwood seeds on top. A formula should then be recited. The victim would be sleepless until they reached the practitioner’s house: this would happen by the time the seventh wick flickered.

-verso,-column-1-(numbered-18).jpg?auto=format)

Love spell that could fetch someone even from across the sea: Papyrus 121(2) verso, column 1 (numbered 18).

After reading these ancient love spells, we definitely prefer our Valentine's Day celebrations to be ‘charmless’.

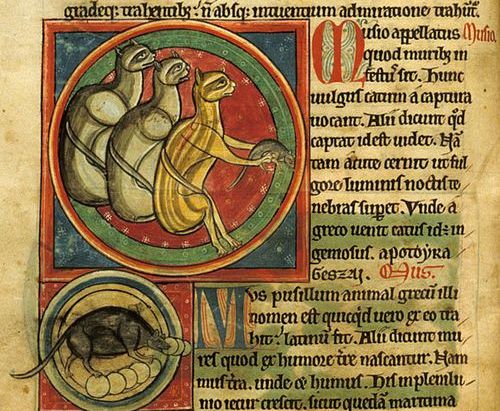

The development of erotic magic continued in the following centuries: you can discover more in our previous blogpost on medieval love spells.

This blog is part of our Medieval manuscripts series, exploring the British Library's world-class collections of manuscripts – including papyri, medieval illuminated manuscripts and early modern state papers.

Our Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts series promotes the work of our curators, who are responsible for these items and thousands more.

Discover medieval historical and literary manuscripts, charters and seals, and early modern manuscripts, from Homer to the Codex Sinaiticus, from Beowulf to Chaucer, and from Magna Carta to the papers of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I.

You can access millions of collection items for free. Including books, newspapers, maps, sound recordings, photographs, patents and stamps.