Oral history at Groundswell 2025

How oral history can help shape agricultural-environmental practices.

How oral history can help shape agricultural-environmental practices.

Blog series Sound and Vision

Author Paul Merchant, Mary Stewart from the National Life Stories, The British Library together with Angela Cassidy and Eleanor Hadley Kershaw from the RENEW Programme, University of Exeter

In July – in a first for the British Library Oral History team – we held a reflective listening session at a major UK agricultural event: Groundswell. Now in its ninth year, Groundswell Regenerative Agriculture Festival takes place each summer at Lannock Farm in Hertfordshire, providing a forum for anyone interested in food production and the environment to learn about the theory and practice of regenerative agriculture.

.jpg?auto=format)

Inside the Workshop Tent. Photo: Angela Cassidy. Photo: Angela Cassidy

In the Workshop Tent, Paul Merchant and Mary Stewart (Oral History, The British Library) and Angela Cassidy (University of Exeter) played audio extracts from two National Life Stories collections: ‘An Oral History of Farming, Land Management and Conservation in Post-War Britain’ (generously supported by Arcadia) and ‘Oral Histories of Environmental Collaboration’ (recorded in partnership with the NERC funded RENEW Programme at the University of Exeter). With some trepidation at the size of the venue for the listening session, we were utterly delighted that 160 farmers, researchers, agricultural advisers, ecologists and others duly pitched up with open ears to listen and respond together to 12 excerpts from the in-depth oral histories.

In one of the audio clips, historical geographer John Sheail reflects on attempts by ecologists and agricultural scientists to bridge the working worlds of farming and environment in the 1980s and 1990s:

And there was this meeting – there were a number of meetings going on and they were valuable in the sense that I think in those meetings for the first time those primarily interested in the science within the agricultural and conservation lobbies felt able to talk to one another and be heard to be talking without possibly incurring censure from one or the other sides. And of course there was common ground, which was no surprise: Mike Way who was a member of the Wildlife and Toxic Chemicals Section when I was there, Mike Way had come from a wholly agricultural-horticultural background. So there was a common language there if only they would use it. And they had begun to use it by the early eighties. And those meetings – there were painful episodes in them; I do remember one when John Jeffers completely lost his temper at the rubbish statistically that was being spouted by someone when he really should have shut up [laughs] and tolerated it. There were those, but yes, there was beginning to be something of a rapport developing; things were improving let us say. And then by the 1990s Terry and I were attending agricultural conferences run by MAFF and saying our piece. It did improve. But it was a struggle initially.

In another, co-founder of Groundswell John Cherry speaks of his joy at seeing farmland birds return to fields under ‘no-till’ (no-ploughing) systems:

I remember coming back from Tony Reynolds’ place so determined that that was it – we went all in, no-till, after visiting that. And it wasn’t just seeing all his crops look so fantastic. It was, you know, he’d drive us around and stop at a field and go in and everywhere we went there were skylarks – just would rise up and would be singing and – I can’t hear that pitch unfortunately but I can see their little beaks opening and shutting. And I said to Tony – because we were experimenting with skylark nesting patches and things; in those days the government was encouraging us to leave, turn the drill off, your seed drill, when you’re planting a field, so you had patches that didn’t have wheat growing or barley or oats or whatever you were planting but just a few weeds and that was considered to be good for skylarks. And we’d been doing this and getting paid a fiver a patch or whatever it was the government were offering – trying to encourage our skylarks. And I said to Tony, ‘I can’t believe the number of skylarks; are you putting your skylark nesting patches in?’ And he said, ‘no, no they just like no till farming’. And I thought, yeah whatever, you know. And then two years later or whatever when we were, everything was no till you know the sky was full of skylarks and I thought, you know, actually they do, you know. But I don’t know, I’m still not really sure why; presumably it’s the more insects, whatever skylarks are eating and the seeds on the ground and they’re less likely to get run over when they’ve made their nest. But we’ve still got skylarks everywhere and it’s just an utter joy to see them – and meadow pipits and corn buntings and all sorts of things which are you know meant to be practically extinct just thrive on a no-till system.

.jpg?auto=format)

John Cherry (right) with Paul Merchant outside the Workshop Tent. Photo: Mary Stewart. Photo: Mary Stewart

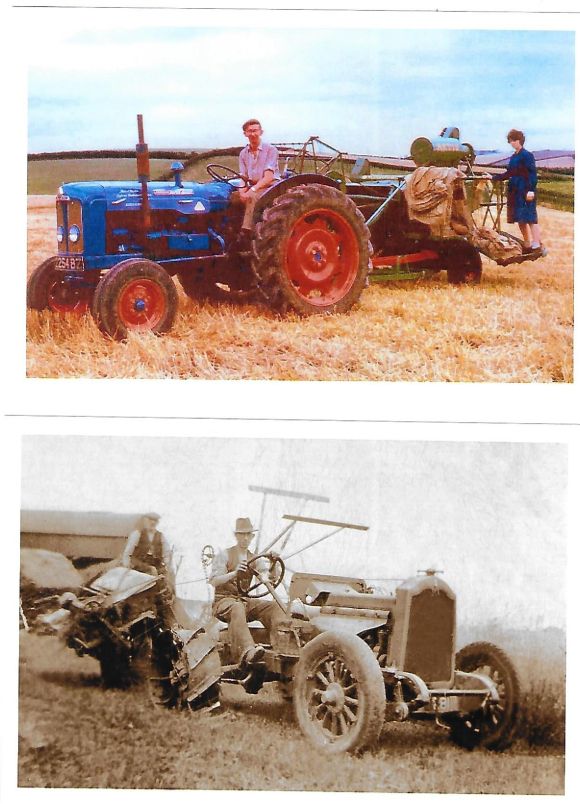

In the session’s final extract, Northern Ireland farmer John Rankin reminds us to listen to earlier generations as we experiment with farming systems fit for the future:

Given this new current situation we’re in about climate change, we are looking at different grasses and not just rye grasses. [...] there are a lot of things that we can learn from how our fathers and grandfathers farmed and I think if we can harness that, I’m a great optimist when it comes to human race.

.jpg?auto=format)

John Rankin and sister in the 1960s (top) and John Rankin’s father and grandfather in 1933 (bottom). Courtesy of Ian Rankin. Courtesy of Ian Rankin

These and other audio clips – many of which you can listen to on a British Library Soundcloud playlist – prompted much thought and discussion. The hubbub of conversation in the Workshop Tent after we played each cluster of clips was amazing to experience and we are convinced of the role of oral history in helping to shape agricultural-environmental practice and policy in the present and future. The session at Groundswell is one in a series of interactive sessions in summer 2025 as part of an AHRC Impact Accelerator Award (University of Exeter Translational Funding). We are currently assessing how NLS can raise further funds for interviewing and outreach in this subject area.

.jpg?auto=format)

Sounds of soil sign. Photo: Paul Merchant. Photo: Paul Merchant

Elsewhere at Groundswell, other kinds of listening experience were on offer. Following the sign in the photograph, we found ourselves listening to subterranean sounds of soil biology recorded by researchers at Rothamsted Research and a number of universities.