Meanwhile, Marconi had less scruples. On 12 December 1901, Marconi used Bose’s 1899 improved version of the coherer to receive the first transatlantic wireless signal. Marconi also applied for a British patent on the device that was not his, in which he did not even mention Bose’s name. Marconi deliberately muddied the waters when presenting 'his' invention at a lecture at the Royal Institution on 13 June 1902. As Probir K Bondyopadhyay writes: 'By the time Marconi gave his lecture at the Royal Institution, he was already under attack by his own countryman, and Marconi, through his careful choice of words, caused deliberated confusions and, using clear diversionary tactics, shifted attention to works of Hughes, who was already dead at that time'.

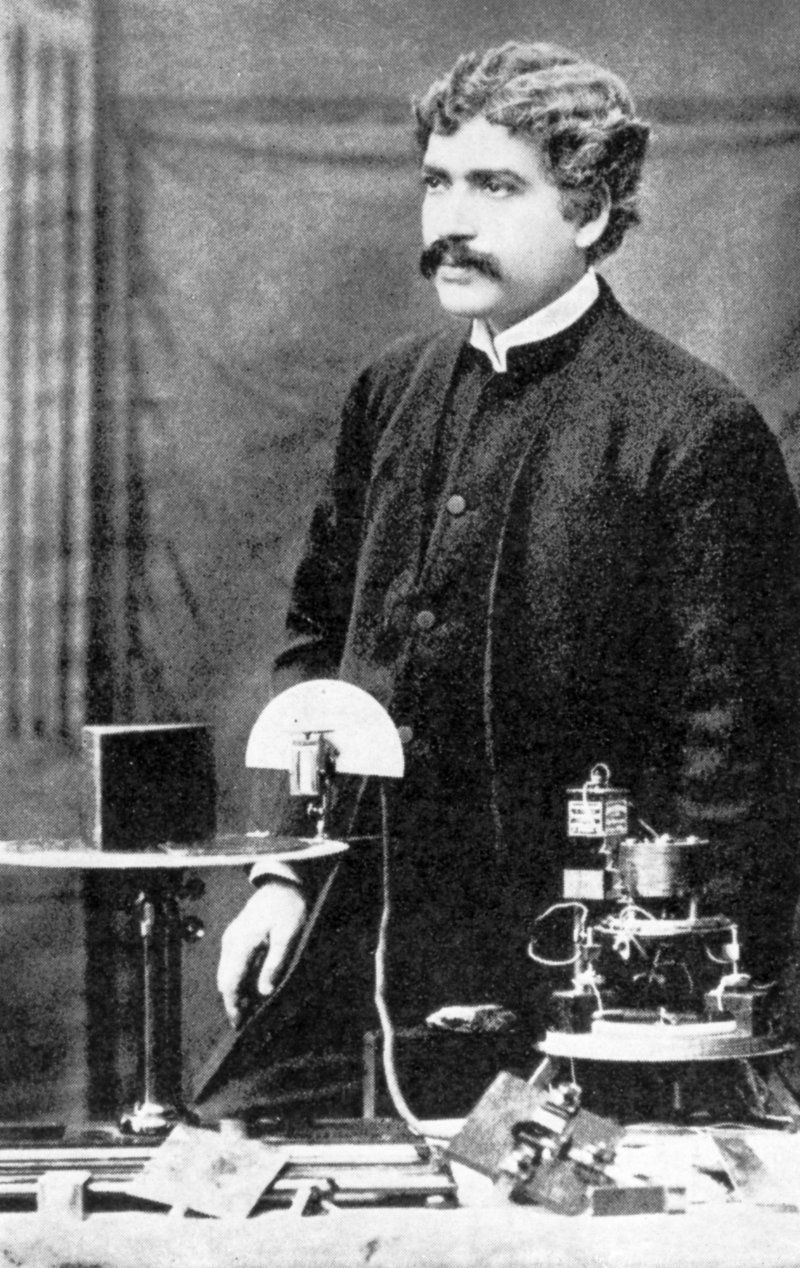

Bondyopadhyay’s article was published in 1998. It took almost a century to unveil the true origins of the device that brought us wireless telegraphy and the radio and to give due credit to Bose. Like the astronomer in The Little Prince, Bose did not play by the rules of Western science, and therefore nobody listened. But also like his fictional counterpart, Bose changed garb. And suddenly, people did listen.

Further reading

Bose's legacy and his contributions to the invention of wireless telegraphy are still a contested issue. For a differing account on the 'Boseian myth', see Subrata Dasgupta's book Jagadis Chandra Bose and the Indian Response to Western science, particularly pages 76-83 and 250-254.