The Nature of Gothic

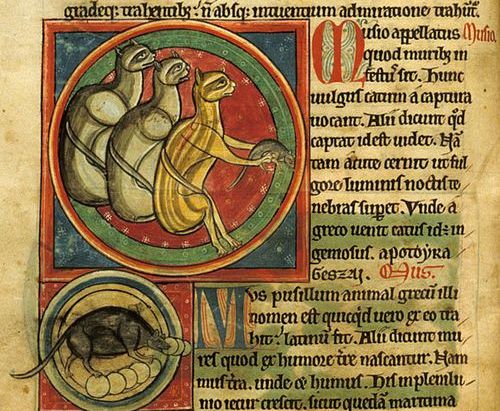

A new exhibition at the Blackburn Museum & Art Gallery explores the origin and significance of decorative flowers in the margins of medieval prayer books.

25 September 2025A new exhibition at the Blackburn Museum & Art Gallery explores the origin and significance of decorative flowers in the margins of medieval prayer books.

25 September 2025Blog series Medieval manuscripts

Author Elena Lichmanova, Curator of Illuminated Manuscripts

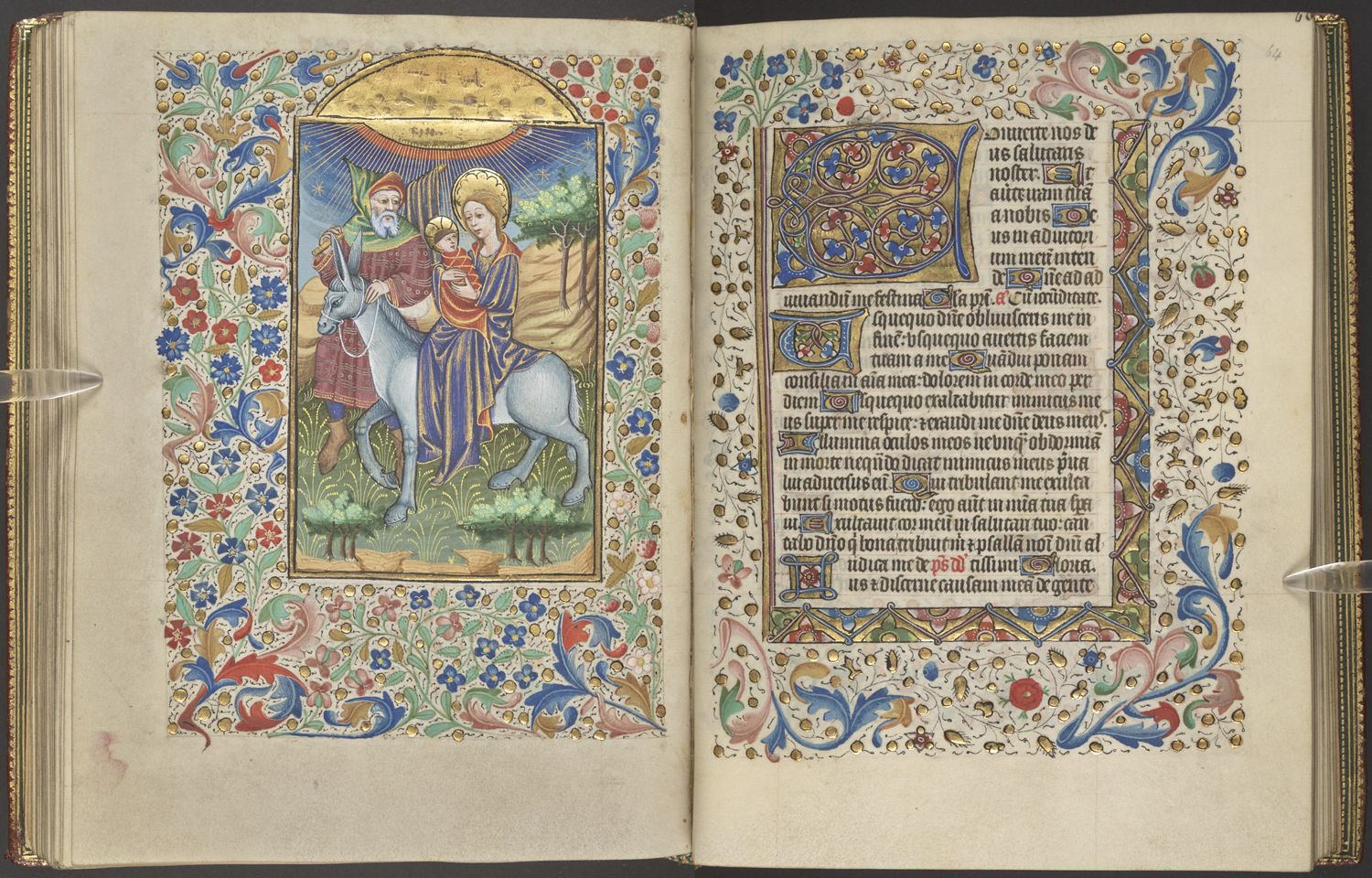

Mary, Joseph and Christ flee to Egypt in the magnificent miniature that opens the night prayer (compline) of the Entwistle Hours, a deluxe 15th-century prayer book. Its medieval beholder would have gazed upon these pages just before going to sleep. At that late hour, not only the Flight to Egypt and the words of compline accompanied the viewer’s devotion, but also the swirling acanthus, the speedwells, roses, strawberries and cornflowers that envelop the pages in a strikingly colourful bouquet. In the 15th century, it was so common to find a flowering meadow in the margins of a Book of Hours that a page without it may have looked strangely bare. How did this flowering border come to be? Did it have any significance in devotional practice?

The Flight into Egypt, in the Entwistle Hours (England and Northern France, c. 1440): Sloane MS 2321, ff. 63v–64r

The Nature of Gothic: Reflecting the Natural World in Historic and Contemporary Artistic Practice, which opened at Blackburn Museum & Art Gallery on 13 September, is a new exhibition that delves into such questions. The British Library is delighted to have loaned several splendid manuscripts to the show. They have travelled to Blackburn to complement the collection of rare books and manuscripts gathered by Robert Edward Hart (d. 1946), a Blackburn rope maker, which shapes the core of the exhibition. Hart’s will ensured that after his death the collection will be divided between his hometown, Blackburn, and his alma mater, the University of Cambridge.

The miniature of Pentecost surrounded by a floriate border with two red and white roses in the Book of Hours (Master of Edward IV, c. 1480–1490): Blackburn Museum & Art Gallery, MS Hart 20884, f. 40v

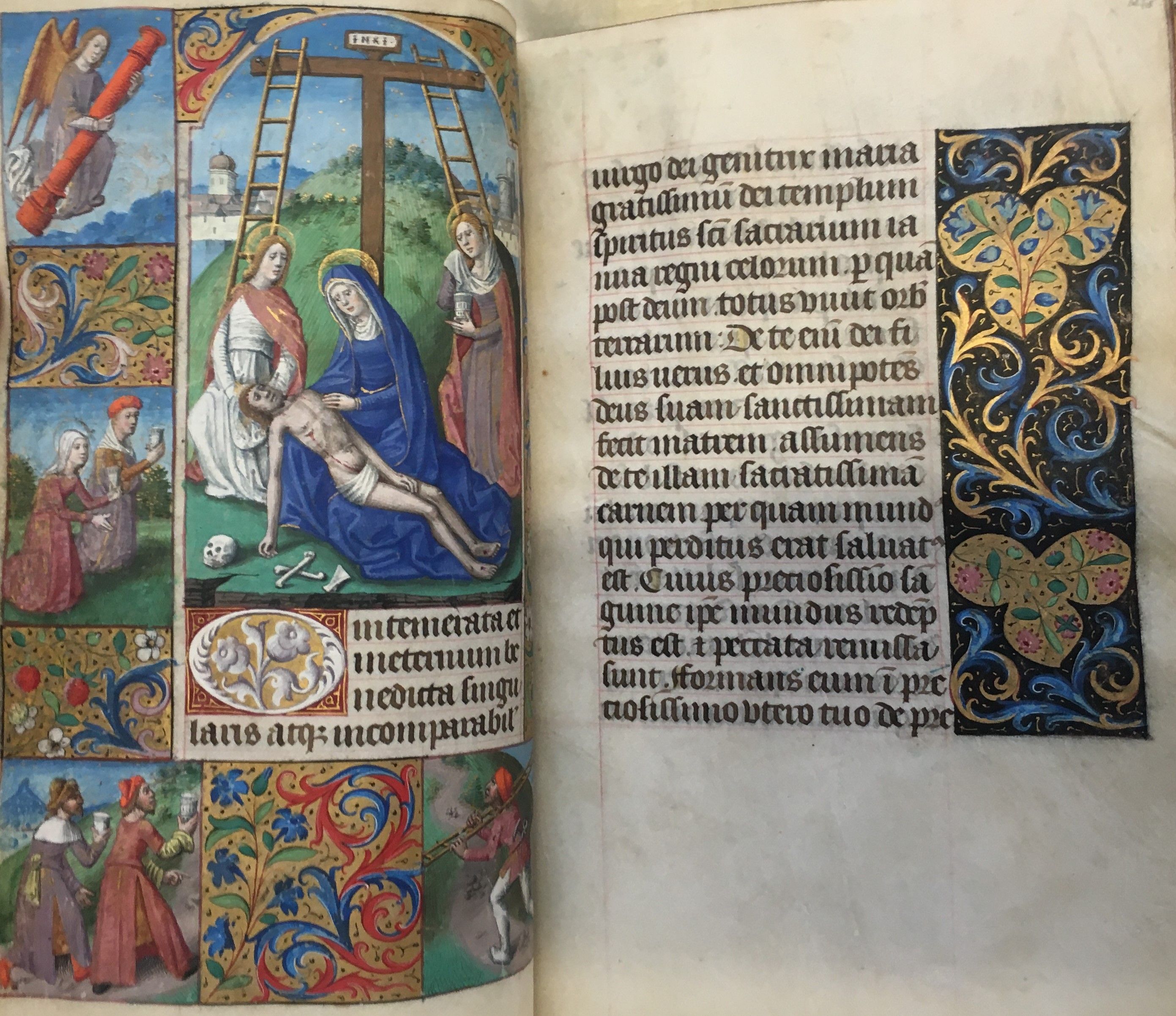

Flowers and plants in art can simply be decorative, but when they appear in medieval devotional manuscripts, their significance may extend beyond mere aesthetics. Psalters and Books of Hours contain daily prayers as well as records of important religious festivals. Flowers were often included in religious ceremonies such as the feasts of saints, being offered to images of saints or the Virgin Mary as expressions of deep veneration. Rituals involving plants and flowers sometimes had specific symbolism. At Pentecost, for instance, petals were scattered in the air to represent the descent of the Holy Spirit upon Christ’s disciples. Like flowers in Christian services, the blossoming illuminations of religious books could take on a special meaning.

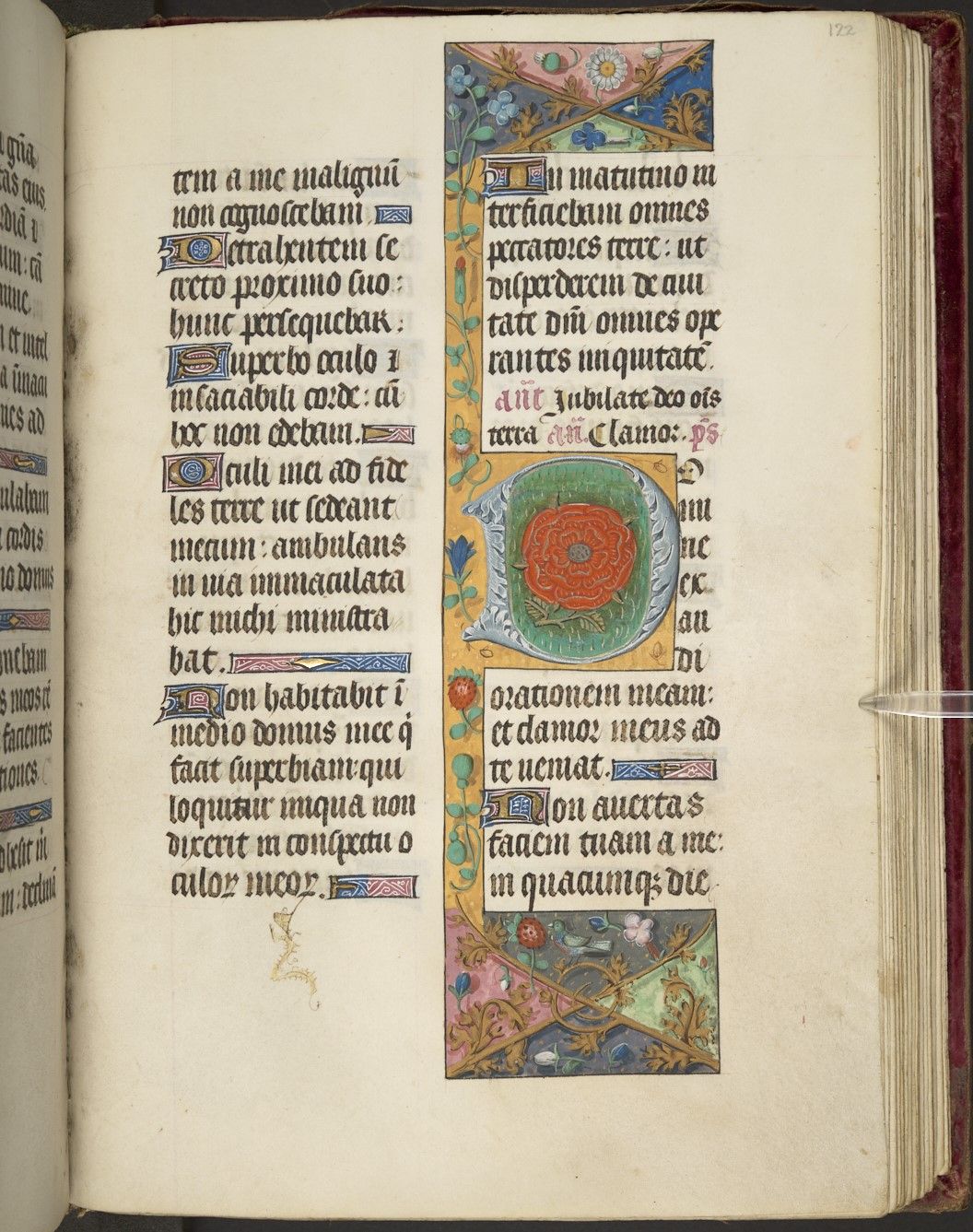

A rose in the initial ‘D’[omine], in the Lucas Psalter (Master of Edward IV, c. 1480–1490): Add MS 89428, f. 122r

One manuscript loaned by the British Library to Blackburn is the Lucas Psalter, made in Bruges for an English patron in the late 15th century. In this Psalter, a large naturalistic rose reigns over the initial ‘D’[omine] at the beginning of the supplication, ‘Lord, hear my prayer’. The symbolic association between Domine ‘Lord’ and this flower was justified by the rose’s privileged status in medieval thought. According to John of Gaddesden, a 14th-century physician, the rose surpasses all flowers. Such exceptional attitude to roses made them a perfect metaphor of Christ as well as a versatile symbol of power. Here, in the Lucas Psalter, grand red roses punctuating the Psalms may serve as reminders of Christ’s sacrifice while also referring to the possibility that the manuscript was commissioned by someone from Lancashire (denoted by the red rose of Lancaster).

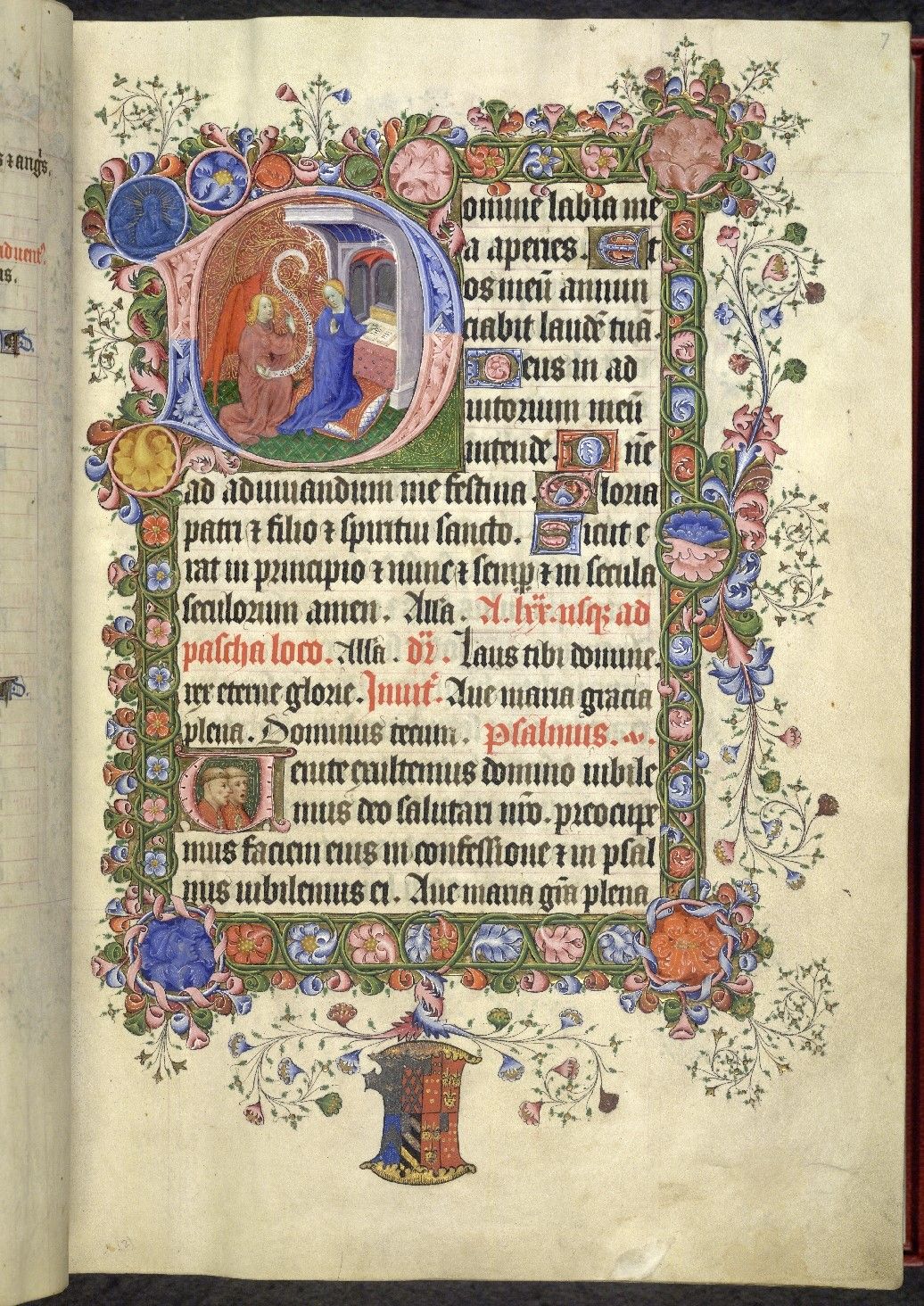

A historiated initial ‘D’ with the Annunciation, surrounded by a floriate border of ivy and acanthus, in the Bedford Psalter and Hours (England, 1414–1422): Add MS 42131, f. 7r

Perhaps the most persistent motifs in the border decoration of illuminated manuscripts are the grape vine, ivy and acanthus. All three share the same irresistibly fluid movement, so convenient in creating varied patterns and universally loved by medieval illuminators. The grape vine provided a suitable accompaniment to the religious texts. It bore deep associations with the communion wine and the sacrificial blood of Christ, but its significance went beyond religious symbolism: such was its persistence in book decoration that it eventually gave its name to the ornamental foliage design: vignette. Ivy and acanthus proved as popular as the grape vine. Exquisite examples fill the margins of the Bedford Psalter and Hours made for John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford (d. 1435), and in the Book of Hours from the Hart collection that may have been produced by (or with the influence of) the same workshop. The flawlessly refined acanthus in the Book of Hours made by the workshop of Maître François gives away that it is a polished Parisian production.

Borders filled with acanthus in the Book of Hours by the workshop of Maître François (Paris, c. 1480): Blackburn Museum, MS Hart 20932, ff. 23v–24r

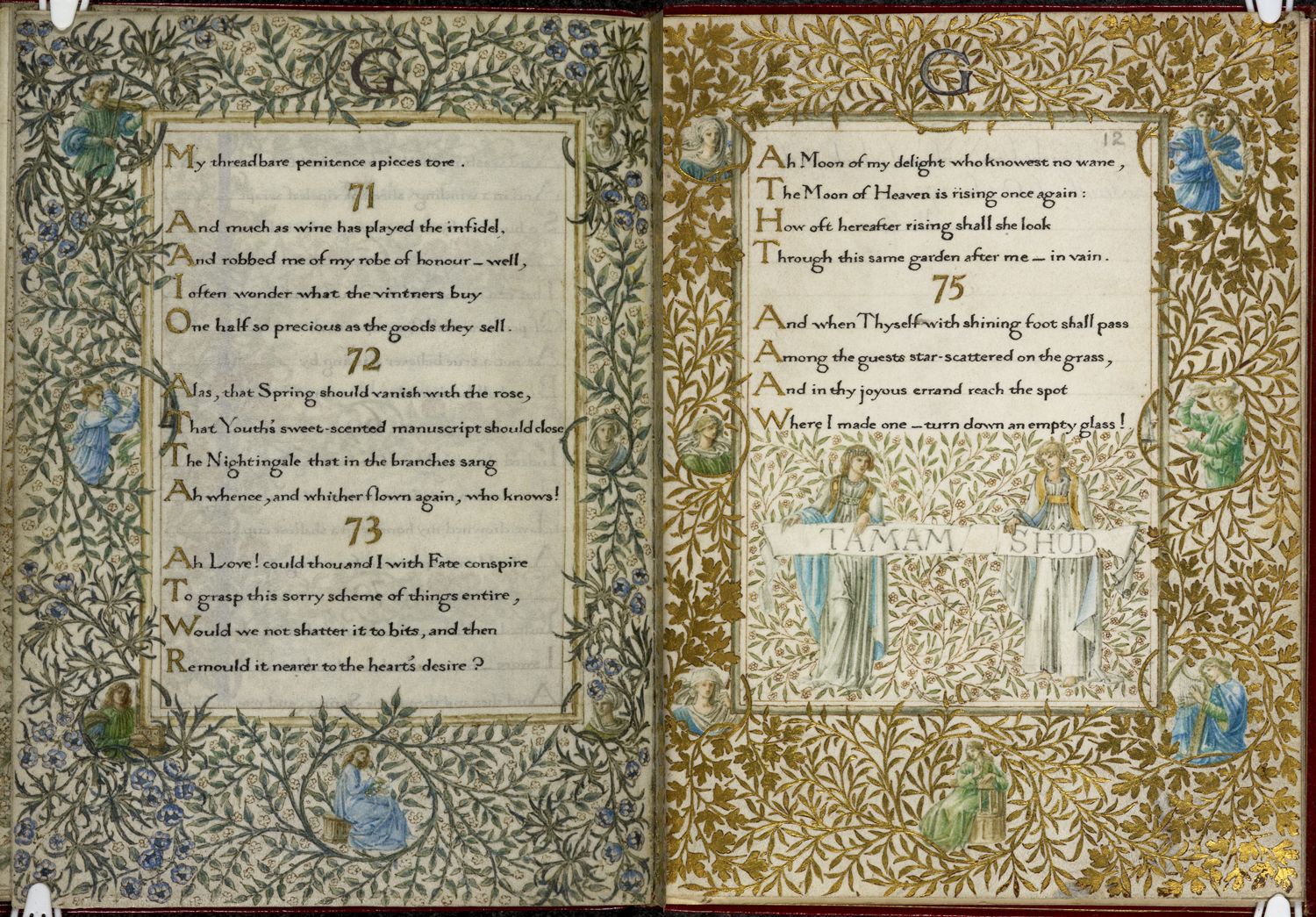

The medieval margin is only a starting point for ‘The Nature of Gothic’. An imaginative metamorphosis of the foliage design in the Arts and Crafts movement is showcased in the works of William Morris (d. 1896), who gave new life to medieval decoration. An eye-catching example is the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam that Morris copied by hand as a birthday present for Georgiana Burne-Jones (d. 1920), the artist and wife of Edward Burne-Jones (d. 1898). The text is written in English, the Rubaiyat having been translated from Persian by Edward FitzGerald in 1849. Morris painted willows and grape vines, in watercolour and gold, in the margins of the book, while Edward Burne-Jones designed the cameos entwined in the deluxe foliage. On every page a letter ‘G’ for Georgiana is hidden in the floriate bushes. This reference to the medieval floriate border reveals something that is not medieval: the Victorian fascination with distant cultures and the pursuit of the national past.

Rybaiyat of Omar Khayyam, with calligraphy and ornamentation by William Morris, and illustrations after Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones by Charles Fairfax Murray (England, 1872): Add MS 37832 ff. 11v–12r

Case with seven British Library manuscripts paired with manuscripts from the Hart collection, at the exhibition ‘The Nature of Gothic’

This blog is part of our Medieval manuscripts series, exploring the British Library's world-class collections of manuscripts – including papyri, medieval illuminated manuscripts and early modern state papers.

Our Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts series promotes the work of our curators, who are responsible for these items and thousands more.

Discover medieval historical and literary manuscripts, charters and seals, and early modern manuscripts, from Homer to the Codex Sinaiticus, from Beowulf to Chaucer, and from Magna Carta to the papers of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I.

You can access millions of collection items for free. Including books, newspapers, maps, sound recordings, photographs, patents and stamps.