Tulips: Dutch, Turkish, or Flemish?

Learn about the Flemish botanists and diplomats who first introduced the tulip to Western Europe, sparking a fascination that grew into Tulipmania and endures today.

8 August 2025Learn about the Flemish botanists and diplomats who first introduced the tulip to Western Europe, sparking a fascination that grew into Tulipmania and endures today.

8 August 2025Blog series European Studies

Author Marja Kingma, Curator of Germanic Collections

One of the labels in our previous exhibition, Unearthed: The Power of Gardening mentions the ‘Austrian Ambassador to the Ottoman court’ as the person who brought the tulip to Western Europe. It does not state who this person was, however. In this blog post, I will tell you a bit about him and his closest associates.

In fact, there were three men from Flanders who were instrumental in the cultivation and research of the tulip in the Low Countries. All three were employed as plant experts by three generations of Austrian emperors: Ferdinand I, Maximilian II and Rudolf II.

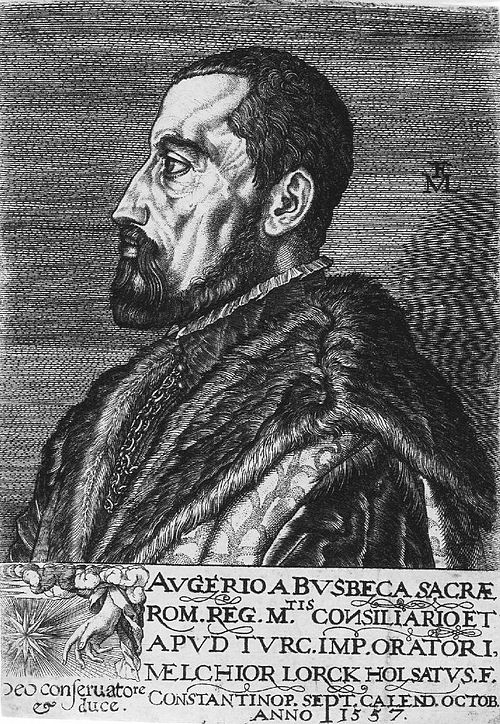

First, Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq. Apart from being a herbalist, he was sent by Emperor Ferdinand I as a diplomat to the Ottoman Court of Süleyman I. He wrote an account of his travels around the Ottoman Empire, mainly the areas of modern-day Turkey, and republished it as ‘Turkish Letters’ in 1595.

Portrait of Ogier Gheselin de Busbecq by Melchior Lorck (1557). Image from Wikipedia

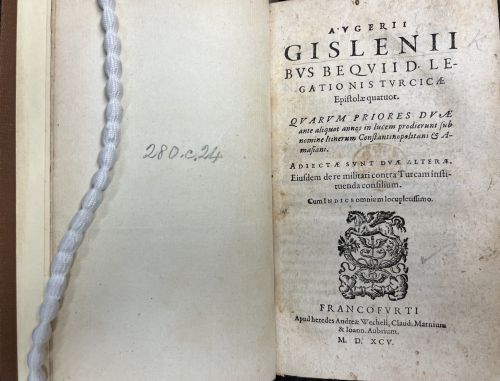

Title page of Avgerii Gislenii Bvs Beqvii Legationis tvrcicae: Epistolae quatuor (Francofvrti, 1595) 280.c.24

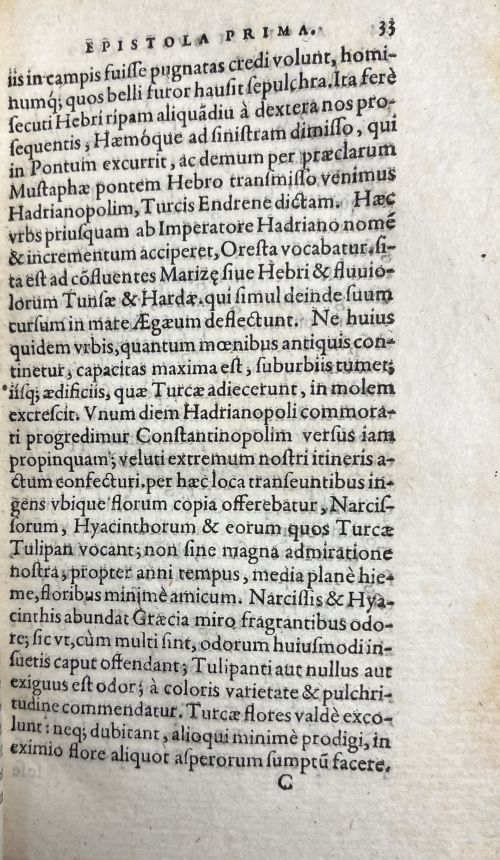

In his first letter, De Busbecq mentions the tulip growing wild (in winter!). He notes that it is not as strong-smelling as the narcissi and hyacinths, which would give one a pounding headache.

Instead, the tulip barely has a scent but makes up for this with its vibrant colours. This is why the Turks loved it so much and, from a very early time, used elegant tulip designs as decorations on tiles and ceramics.

Page from Avgerii Gislenii Bvs Beqvii, Legationis tvrcicae: Epistolae quatuor (Francofvrti, 1595) 280.c.24.

Detail from a 16th-century Turkish tile. Image from Museum With No Frontiers

The second key figure was Carolus Clusius, a botanist and associate of De Busbecq, who helped Clusius secure a post at the Austrian court. When Rudolf II came to power, he was dismissed from the court. Following this, he was appointed a professor in Leiden and became the first Director of the Hortus Botanicus of Leiden University.

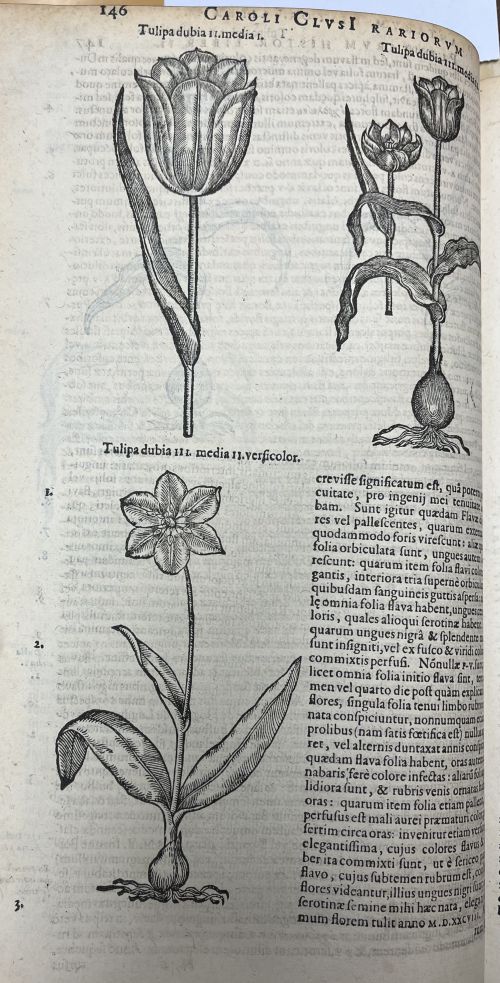

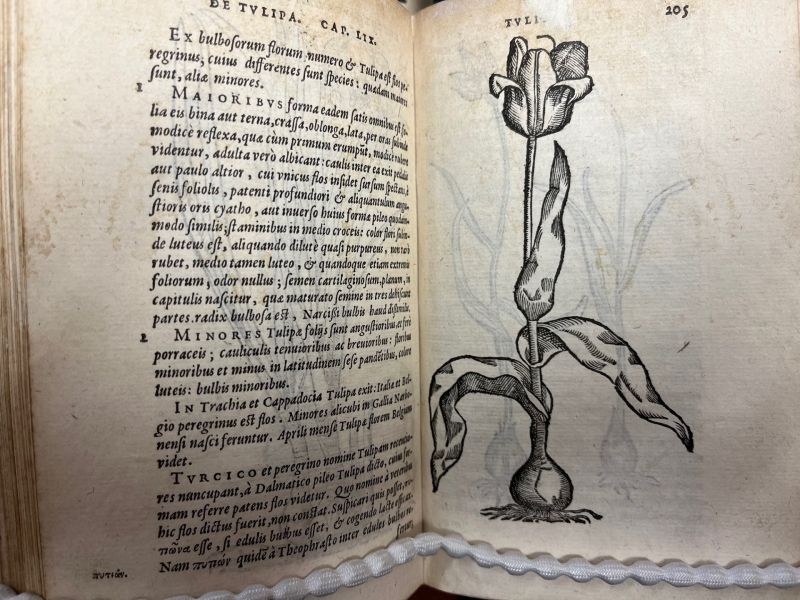

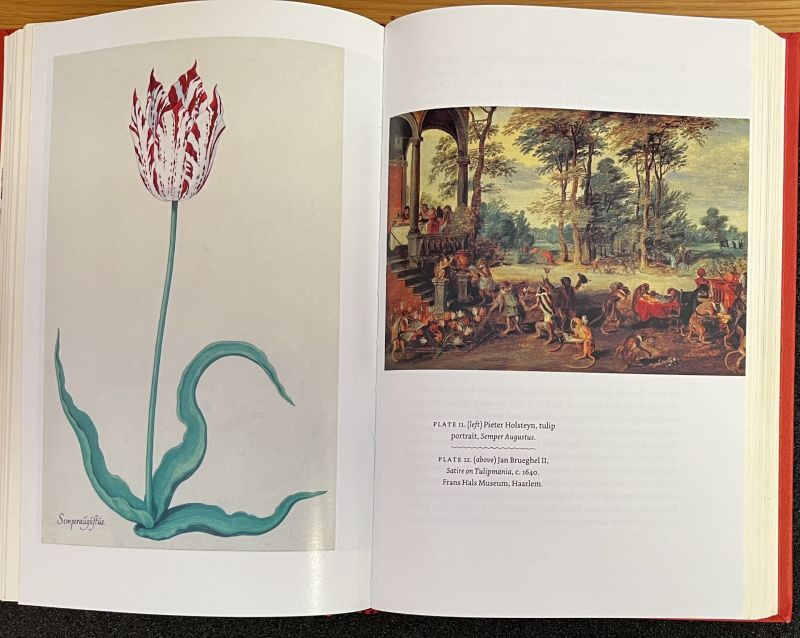

Clusius maintained a large network of academics and plant collectors and sent them tulip seeds and bulbs, thus initiating the trade in tulip bulbs. He published his Rariorum Plantarum Historia, where he documented 22 tulip varieties. He also described the phenomenon of the ‘breaking’ of tulip petals, which resulted in wonderful patterns and fringed petal edges. Clusius noted that a plant that displayed these characteristics would die soon after. He couldn't have known that the 'breaking' was caused by a virus. Nonetheless, tulips with these patterns became so popular that they led to the infamous Tulipmania of 1633 –1637.

Images of tulips in Rariorum plantarum historia by Caroli Clusii (Antverpiæ, 1601) 441.i.8.(1.)

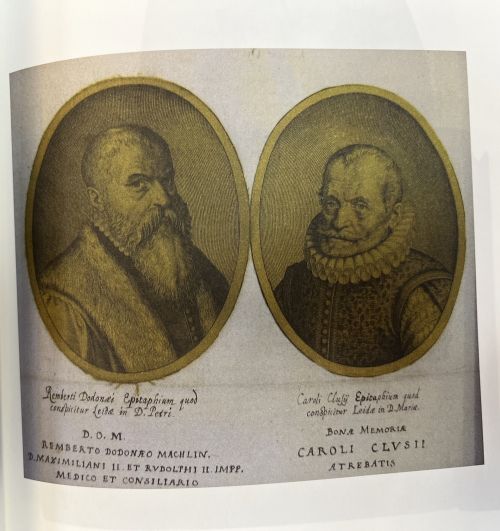

Portraits of Rembert Dodoens and Carolus Clusius on yellow silk (after 1609), from Sylvia van Zanen, Planten op papier (Zutphen, 2019) YF.2020.a.4313

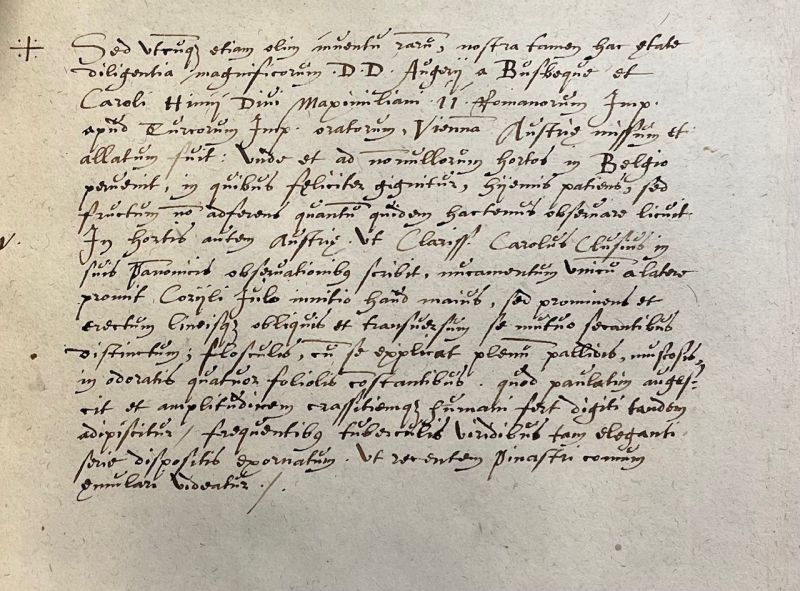

The third person connected to both De Busbecq and Clusius was Rembert Dodoens, who served the Austrian Emperor Maximilian II in the 1580s. Whilst editing the second Latin edition of his herbal using a copy of the first edition of 1583 (442.i.6), he made a note about De Busbecq, Clusius and Maximilian II. Dodoens had included the tulip with an illustration in his other plant book Frvmentorvm Legvminvm... etc. (1569). He does not play a central role in this story, but if you would like to learn more about his work, please check my previous blog post.

Leaf with manuscript notes in R. Dodoens Stirpium historiae pemptades sex, ... (Antwerp, 1583) 442.i.6

Pages from Frvmentorvm Legvminvm (Antverpiae, 1569) 968.g.11(2)

There are many different estimates regarding the cost of a single tulip bulb at the height of Tulipmania. Best estimates range from fl. 3,000 to fl. 4,200 —a very substantial sum and about ten times the annual earnings of a skilled craftsman. However, it is not true that one tulip bulb could buy you multiple properties.

Tulipmania still captures the imagination of many, and understandably so. It is a great story, first spread by the Scottish journalist Charles Mackay in his Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds published in 1841. Several later editions have been released, with some as recent as the 21st century. We now know that he based most of his observations on contemporary parodies rather than hard facts. It was not until the 1980s that historians and economists debunked most of his account. By then, the received wisdom was that large parts of the Dutch population had collectively gone mad and were involved in the trade and speculation in futures—a tool apparently invented during the Tulipmania.

Scholars such as Anne Goldgar delved into the archives and studied the original contracts between tulip bulb traders, including futures on bulbs yet to be grown. Goldgar argues that only a small group of traders were involved and that most contracts were not fulfilled, so no money had actually changed hands. At its height, from 1636 to early February 1637, tulip bulbs reached prices that were simply too high for anyone to afford. On 5 February 1637, a trader tried to sell a bulb for fl. 1,250, but had to lower his price to fl. 1,000, one of the events that would lead to the collapse of the market.

Semper August tulip with ‘breaking’ and a satire on tulipmania by Jan Brueghel II, from Anne Goldgar, Tulipmania (Chicago, London, 2007) YC.2008.a.8160

Since then, more booms and busts have occurred in the flower bulb trade. In recent years, the flower and bulb trade has faced some challenges. This is partly because of changing weather, with droughts affecting the bulb harvest.

However, earnings have remained strong.

In 2024, Royal-Flora Holland, the world’s largest co-operative based in Aalsmeer, auctioned 2.8 billion roses, 1.8 billion chrysanthemums and 1.8 billion tulips, with a turnover of €4.7 billion. The Centraal Bureau voor Statistiek reports that the 1.8 billion tulip bulbs were produced by approximately 896 growers across an area of 15,120 ha, from a total of 1,600 flower growers cultivating 27,000 hectares in total.

The tulip has become a national symbol of the Netherlands, serving as an economic asset and a tourist attraction. The tulip is a subject in art, literature, and culture. It is also sold as a cut flower all over the world. This is all thanks to the Turks, the Flemish... and the Dutch who ran with it, cultivating the flower into a worldwide phenomenon.

Area used to grow flower bulbs has increased in 10 years, decreased in 2024 | CBS 28-3-2025

Tulip Festival Amsterdam - Flower Events in Holland

Frans Willemse and Marja Smolenaars (transl.), The Mystery of the Tulip Painter (Hilversum,1994) YD.2006.b.1048

Arie Dwarswaard and Maarten Timmer, Van Windhandel tot Wereldhandel (Houten, 2010) YF.2012.b.560

This blog is part of our European Studies blog series, promoting the work of our curators, recent acquisitions, digitisation projects, and collaborative projects outside the Library.

Our blogs explore the British Library's extraordinarily diverse collections of material from all over the continent – from Greece to Finland and from France to Georgia, and everywhere in between.

You can access millions of collection items for free. Including books, newspapers, maps, sound recordings, photographs, patents and stamps.