What is a bestiary?

As the Getty's wonderful Book of Beasts exhibition draws to close, it's an apt moment to reflect on the medieval manuscripts we know as 'bestiaries'.

18 August 2019As the Getty's wonderful Book of Beasts exhibition draws to close, it's an apt moment to reflect on the medieval manuscripts we know as 'bestiaries'.

18 August 2019Blog series Medieval manuscripts blog

Author Julian Harrison, British Library

Elizabeth Morrison, one of the curators of Book of Beasts, has described the bestiary as 'one of the most appealing types of illuminated manuscripts, due to the liveliness and vibrancy of its imagery ... All of us can find something to relate to in the bestiary and its animals' ('Beastly tales from the medieval bestiary').

.jpg?auto=format)

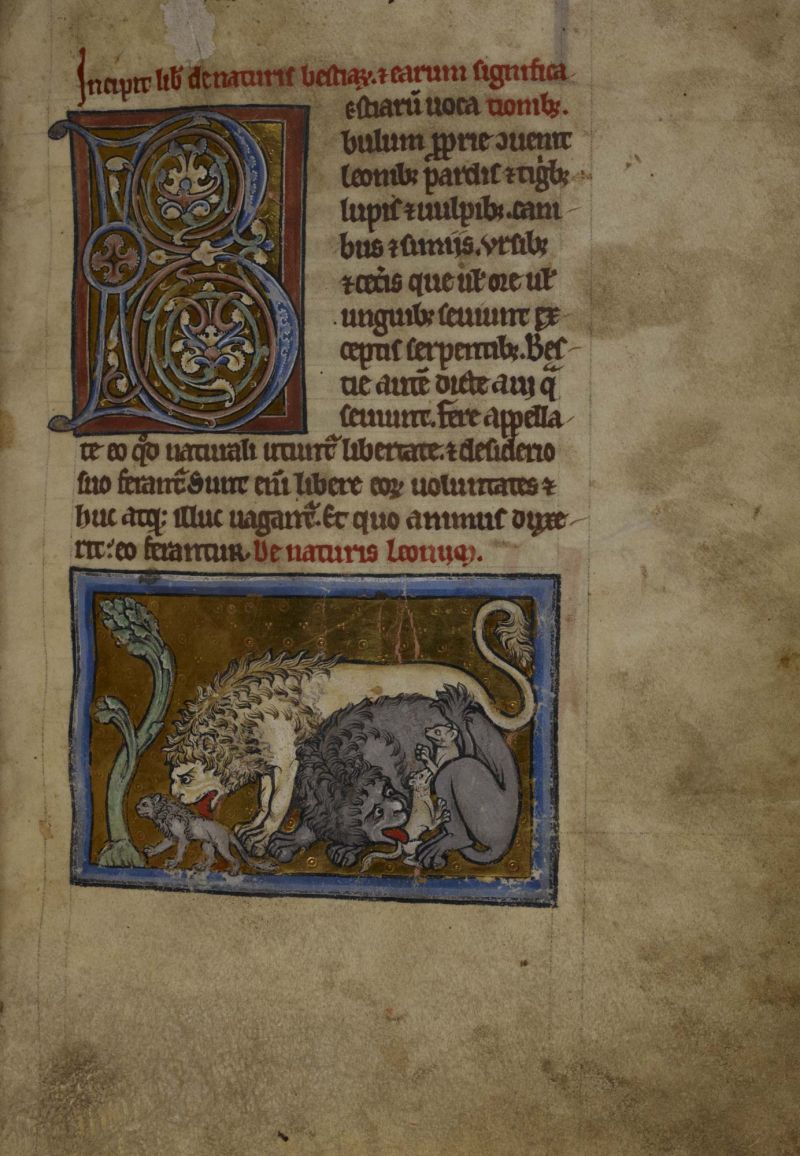

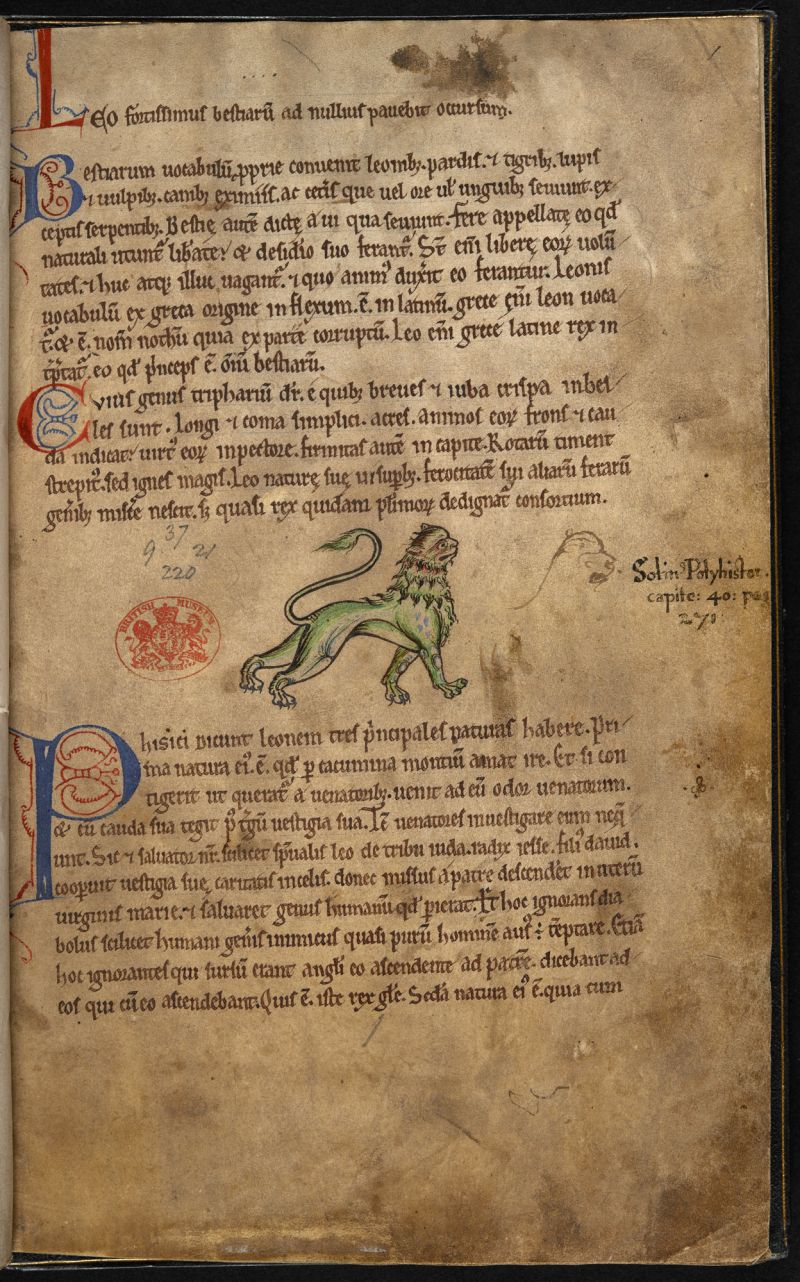

The lion bringing its cubs to life (Royal MS 12 C XIX, f. 6r)

We might regard bestiaries as a kind of medieval encyclopedia relating to natural history, with one notable distinction: each creature was described in terms of its place within the Christian worldview, rather than as a purely scientific phenomenon. The animals were interpreted as evidence of God’s divine plan for the world. This is particularly true of the first animal typically described in the bestiary, namely the lion. One famous bestiary story is that of the birth of lions. Lion cubs were said to be born dead, until on the third day their father breathed upon them, bringing them to life, a reflection of the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ.

.jpg?auto=format)

The opening page of a medieval bestiary (Add MS 11283, f. 1r).

The origins of the bestiary can be traced to the Physiologus, a Greek text devoted to natural history from late Antiquity. Around the 11th century, material was added from Isidore of Seville's Etymologies, a popular early medieval encyclopedia. Bestiaries themselves became popular in England from the 12th century onwards, but they did not all contain the same descriptions or illustrations, leading to them being divided into different families by modern scholars. As Elizabeth Morrison has pointed out, 'the bestiary was not a single text, but a series of changeable texts that could be reconfigured in numerous ways. The number of animals could vary quite significantly, as well as their order'.

.jpg?auto=format)

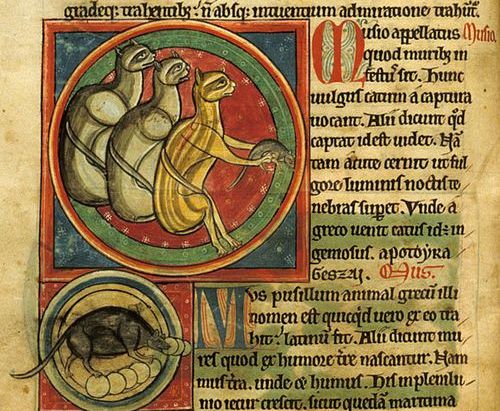

Cats and mice in a bestiary (Royal MS 12 C XIX, f. 36v).

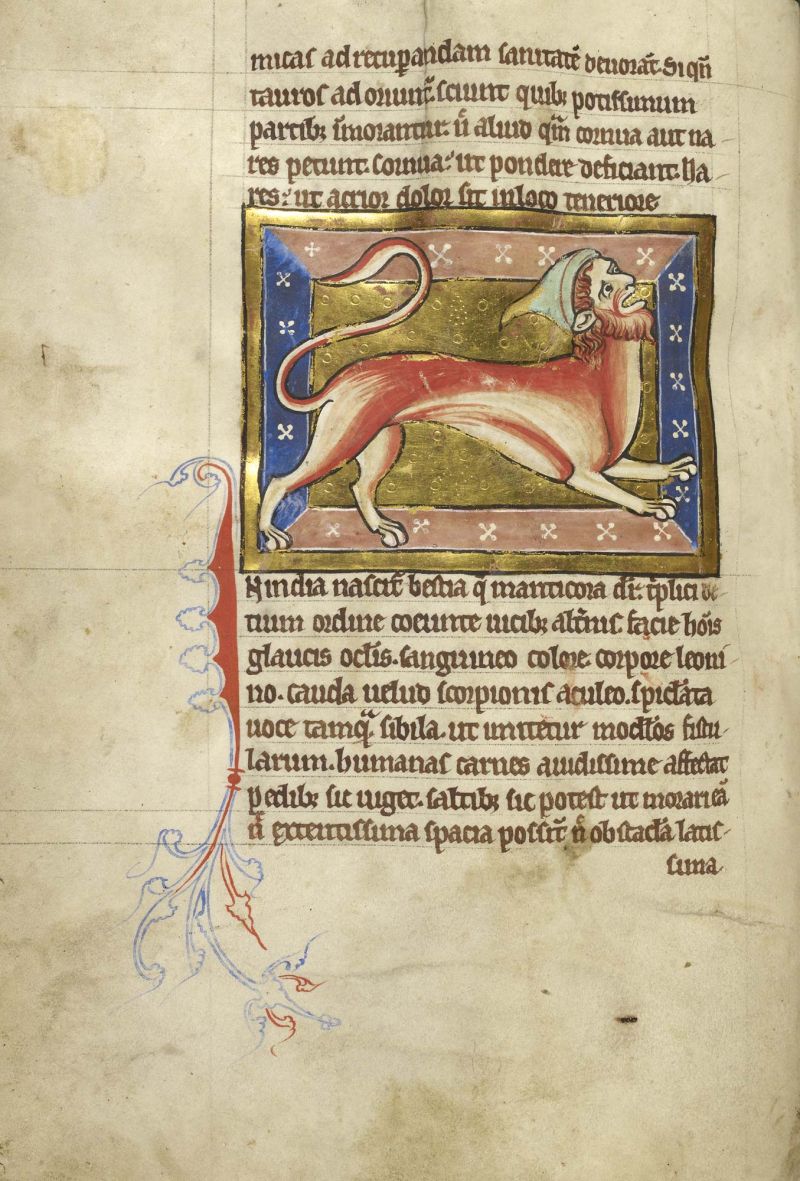

Bestiaries offer an enticing insight into the medieval mind. Some of the creatures they describe would have been very familiar to their original audience, such as cats, donkeys and owls. Others were more exotic, such as crocodiles and elephants, and this is often a source of amusement for modern readers; normally, the artists were relying upon the text and their own imaginations when depicting such beasts, rather than working from first-hand experience.

.jpg?auto=format)

Men mounted on an elephant (Harley MS 3244, f. 39r).

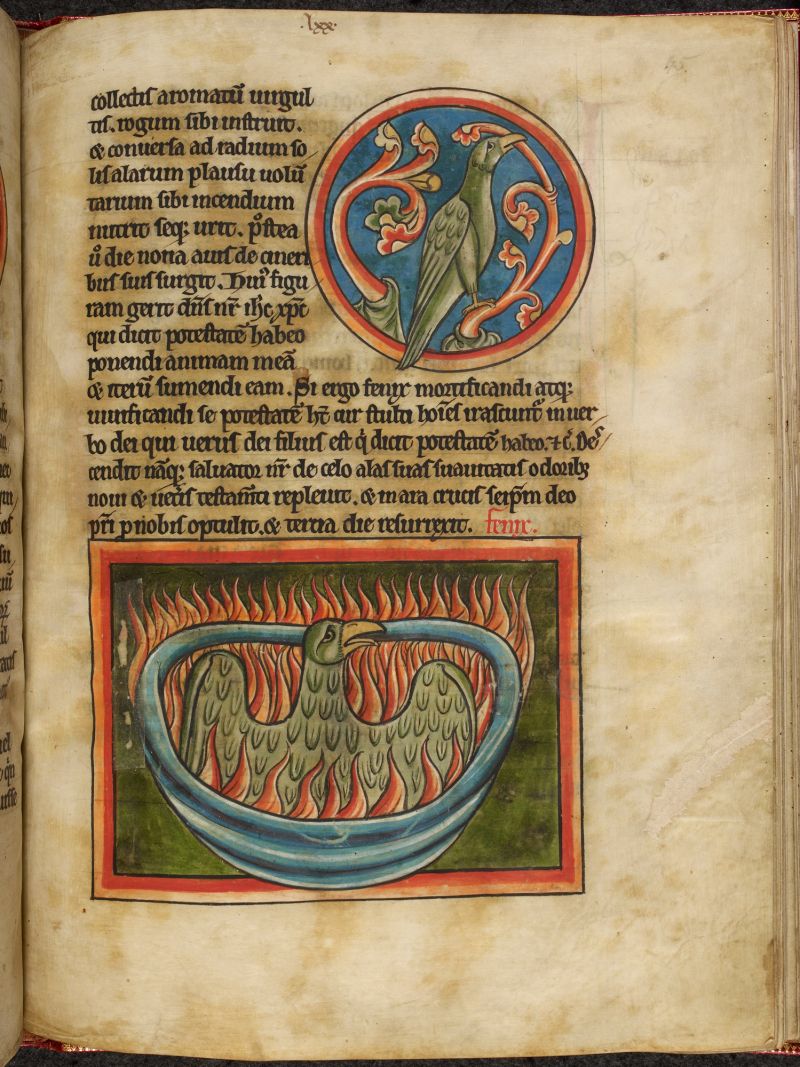

Likewise, bestiaries contain accounts of animals that we would now identify as mythical, such as phoenixes and unicorns. These fantastic beasts inhabited a special place in the medieval imagination, and beyond. You may recognise the illustration of the phoenix, below, from an English bestiary, as one of the stars of the British Library exhibition Harry Potter: A History of Magic.

.jpg?auto=format)

A phoenix in a medieval bestiary (Harley MS 4751, f. 45r)

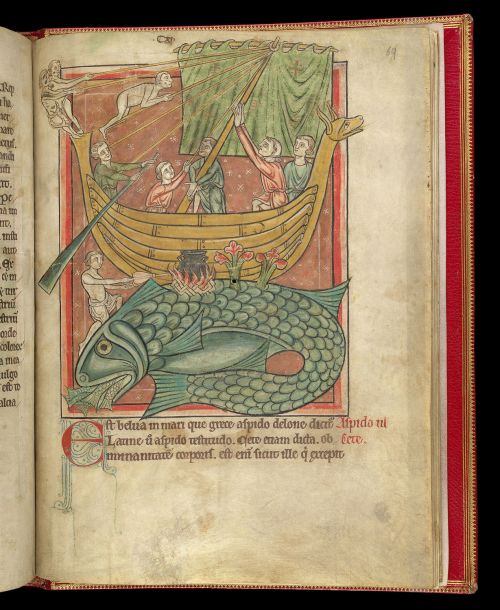

Bestiaries abound with tales of fantastic and fabulous proportions. The story of the whale is a case in point. In bestiary tradition, the whale was so large that it could rest on the surface of the water until greenery grew on its back. Passing sailors, mistaking the animal for an island, would set camp on its back and unsuspectingly light a fire. The whale would then dive back into the ocean, dragging its victims with it.

.jpg?auto=format)

Sailors making camp on the back of a whale (Harley MS 4751, f. 69r)

We have reproduced the tale of the whale in this animation, created as part of The Polonsky Foundation England and France Project: Manuscripts from the British Library and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 700–1200. You could say, we 'had a whale of a time'.

Illuminated Latin bestiaries survive in significant numbers. The Getty's exhibition catalogue lists a total of 62 examples, now dispersed across collections in the United Kingdom, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Russia and the USA. No fewer than 8 are held at the British Library (and we loaned 6 manuscripts in total to Book of Beasts).

.jpg?auto=format)

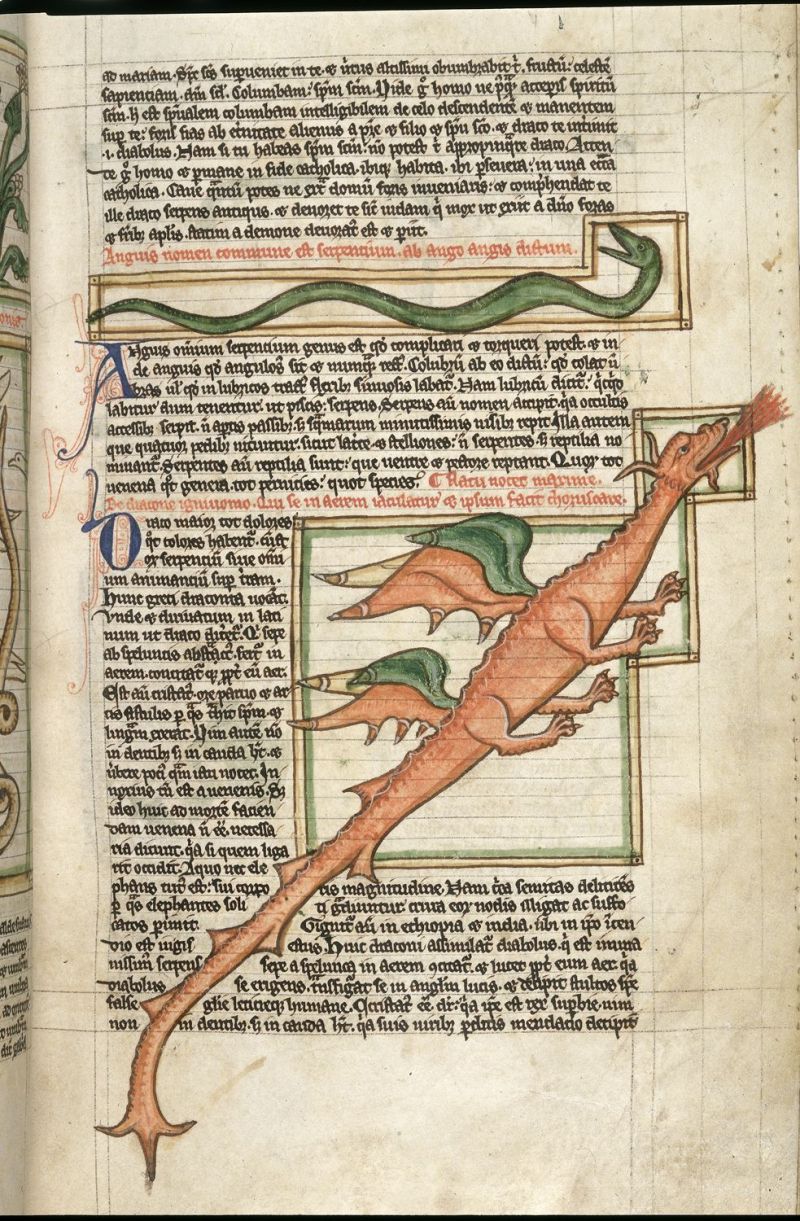

A dragon from an English bestiary (Harley MS 3244, f. 59r).

Here is a list of the illuminated Latin bestiaries in the British Library's collections:

Add MS 11283: England, 4th quarter of the 12th century

Cotton MS Vitellius D I: England, 2nd half of the 13th century

Harley MS 3244: England, after 1236

Harley MS 4751: England, early 13th century

Royal MS 12 C XIX: England, early 13th century

Royal MS 12 F XIII: Rochester, c. 1230

Sloane MS 3544: England, mid-13th century

Stowe MS 1067: England, 1st half of the 12th century

.jpg?auto=format)

Sheep in a bestiary (Sloane MS 3544, f. 16r)

.jpg?auto=format)

A manticore (Royal MS 12 C XIX, f. 29v).

This blog is part of our Medieval manuscripts series, exploring the British Library's world-class collections of manuscripts – including papyri, medieval illuminated manuscripts and early modern state papers.

Our Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts series promotes the work of our curators, who are responsible for these items and thousands more.

Discover medieval historical and literary manuscripts, charters and seals, and early modern manuscripts, from Homer to the Codex Sinaiticus, from Beowulf to Chaucer, and from Magna Carta to the papers of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I.

You can access millions of collection items for free. Including books, newspapers, maps, sound recordings, photographs, patents and stamps.