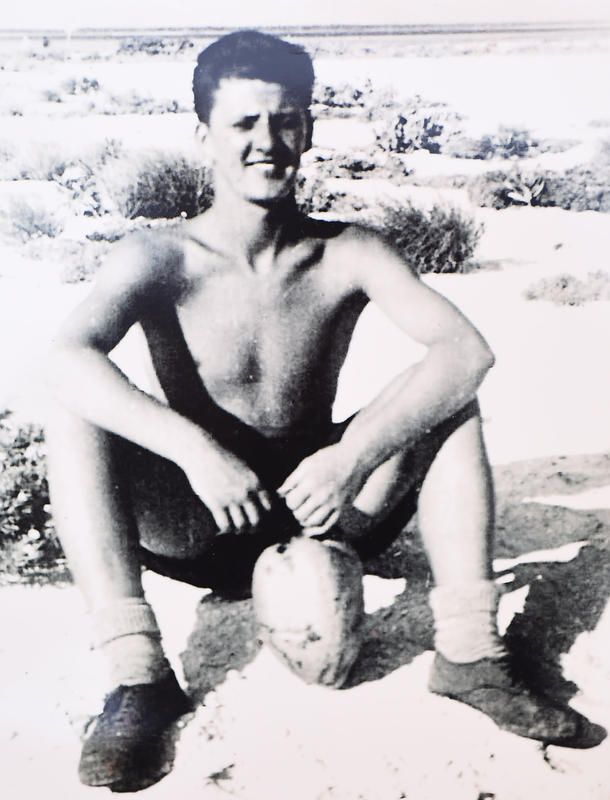

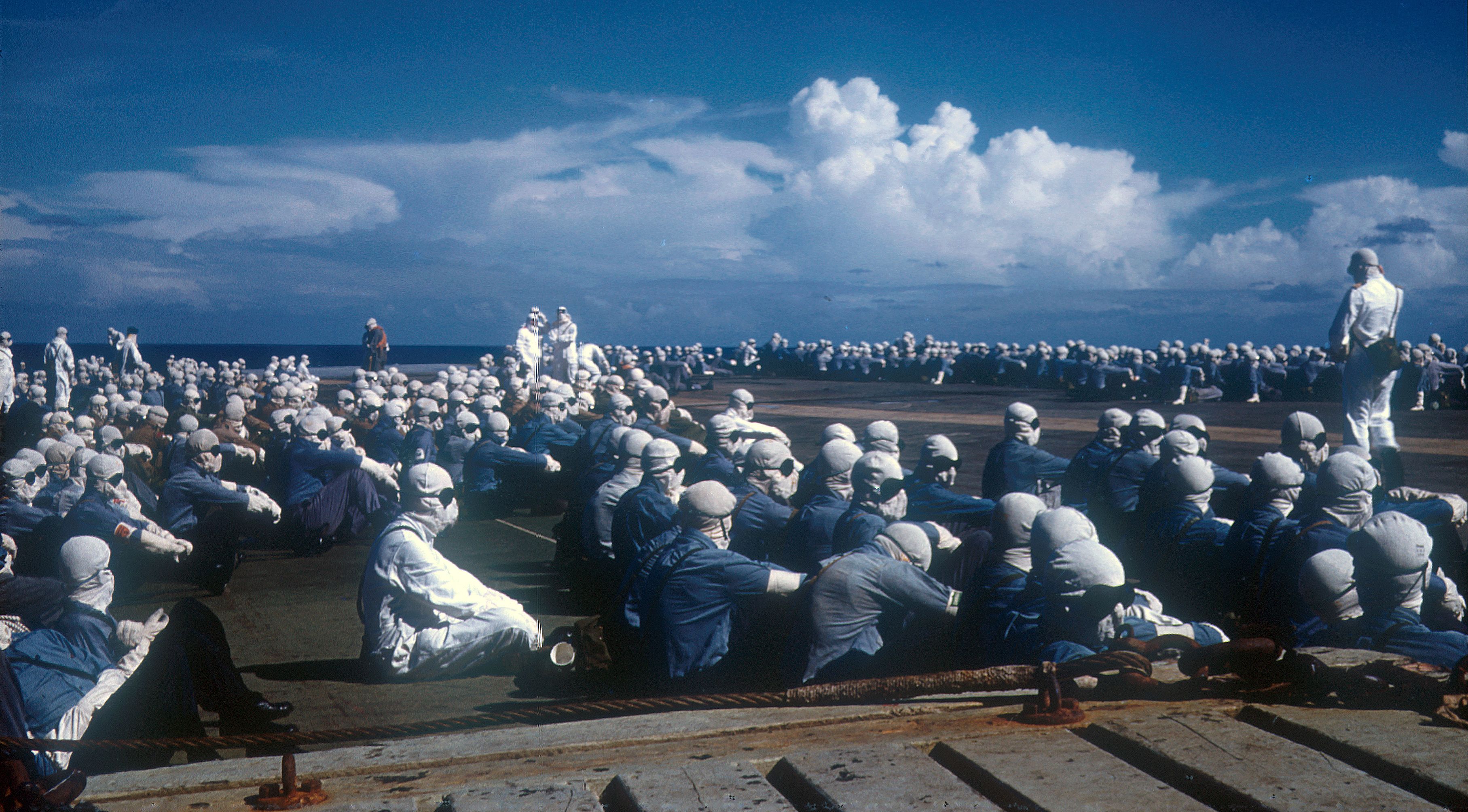

Prior to that, in 1957, I volunteered for Porton Down. It came up on orders when I was at Bicester, volunteers wanted to go to Porton Down for a physiological course. I asked this sergeant, what’s all this about? Didn’t know what physiological meant. So he said, oh, you’re out in the fields, you know, gas capes and all that. I thought, that’s a bit of a change from working in the workshop, I’ll volunteer for that. Well, I got to Porton Down, it was, it was wonderful. It would have been like an officers’ mess, I suppose. Not that I’d know what an officers’ mess was like. And we soon found out, they put us in the gas chambers and they pumped in sarin gas, and there was a big window where the doctors were standing with their white coats and their notes, and I just went, I took a breath of this, I went down, bang. I couldn’t breathe, I was choking, I couldn’t breathe. I thought I was dying, I was nineteen. The Lieutenant Colonel knelt down, put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘This will pass’. Eventually it did. I know my eyes were so – everyone’s – it dilated the pupils, or the pupils got bigger, and anyway, eventually, I know I was playing cards for money and losing and thought it was funny. I never gambled in the army, never gambled anyway. And it so affected our eyes you couldn’t stand bright lights. And, you know, you weren’t allowed to smoke in there, but afterwards, I was I think there for about a week or ten days, they did all sorts of things with us, gave us injections, mustard gas, the gas here.

A scar?

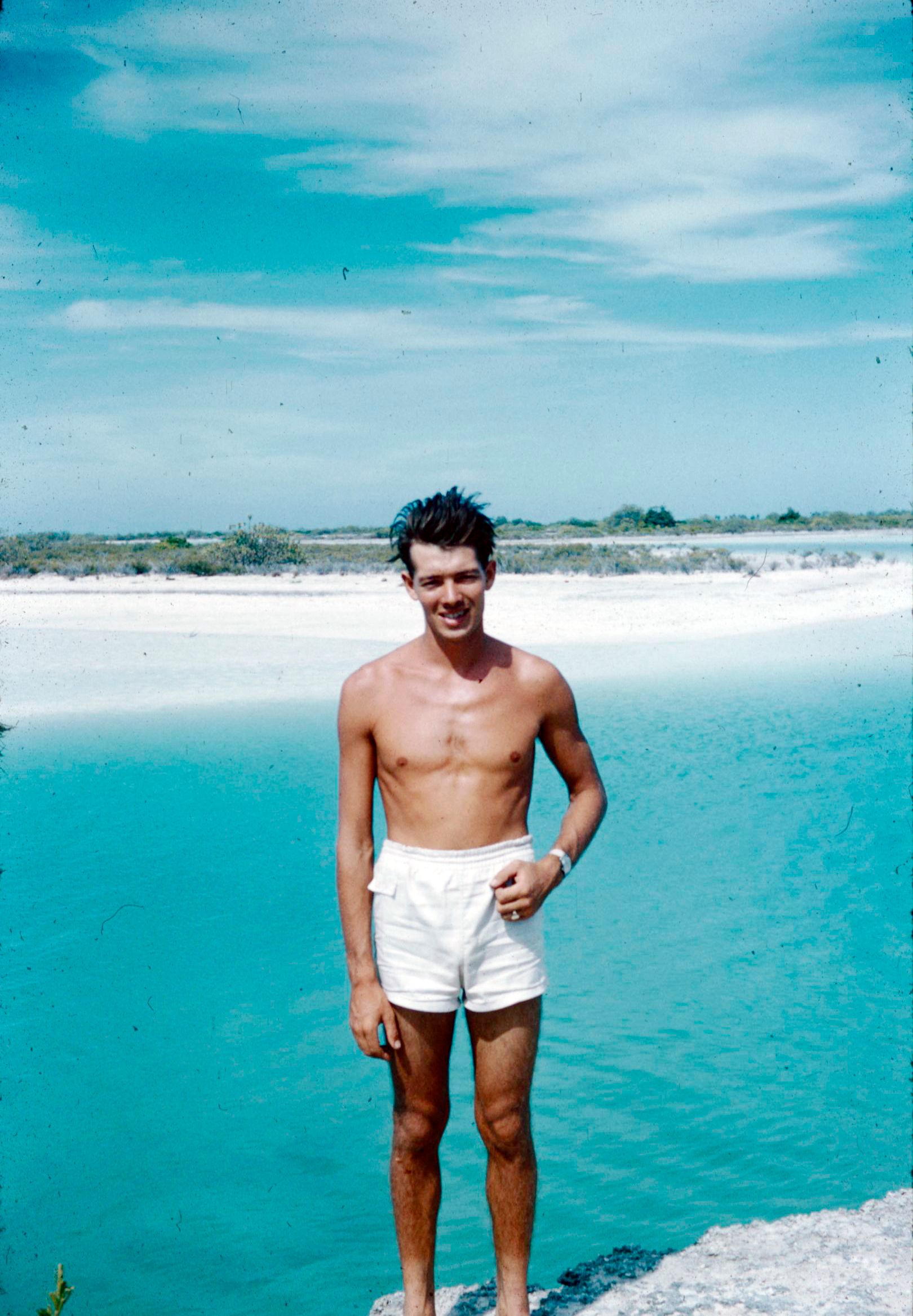

A scar, the round scar. Anyway, I think they… yeah, it is, and you’ll see it now. There, on each arm. And other things they did. And you’d strike a match, you couldn’t even stand the brightness of a match, and you’d, you know, and you’d, you know, like pff pff pff, try and light your fag. [sighs] And it was then, when I used to lay down at night – uh! I couldn’t breathe. And on Christmas Island, that got really, really worse. So I laid down on my back – oh! They call it sleep apnoea now, don’t they?

Yeah.

But I didn’t know that then. I kept reporting sick. Oh, it’s him again, Bonas again. Two codeine and duty. I asked to see a psychiatrist. We haven’t got one on the island.

[ends at 0:03:11]