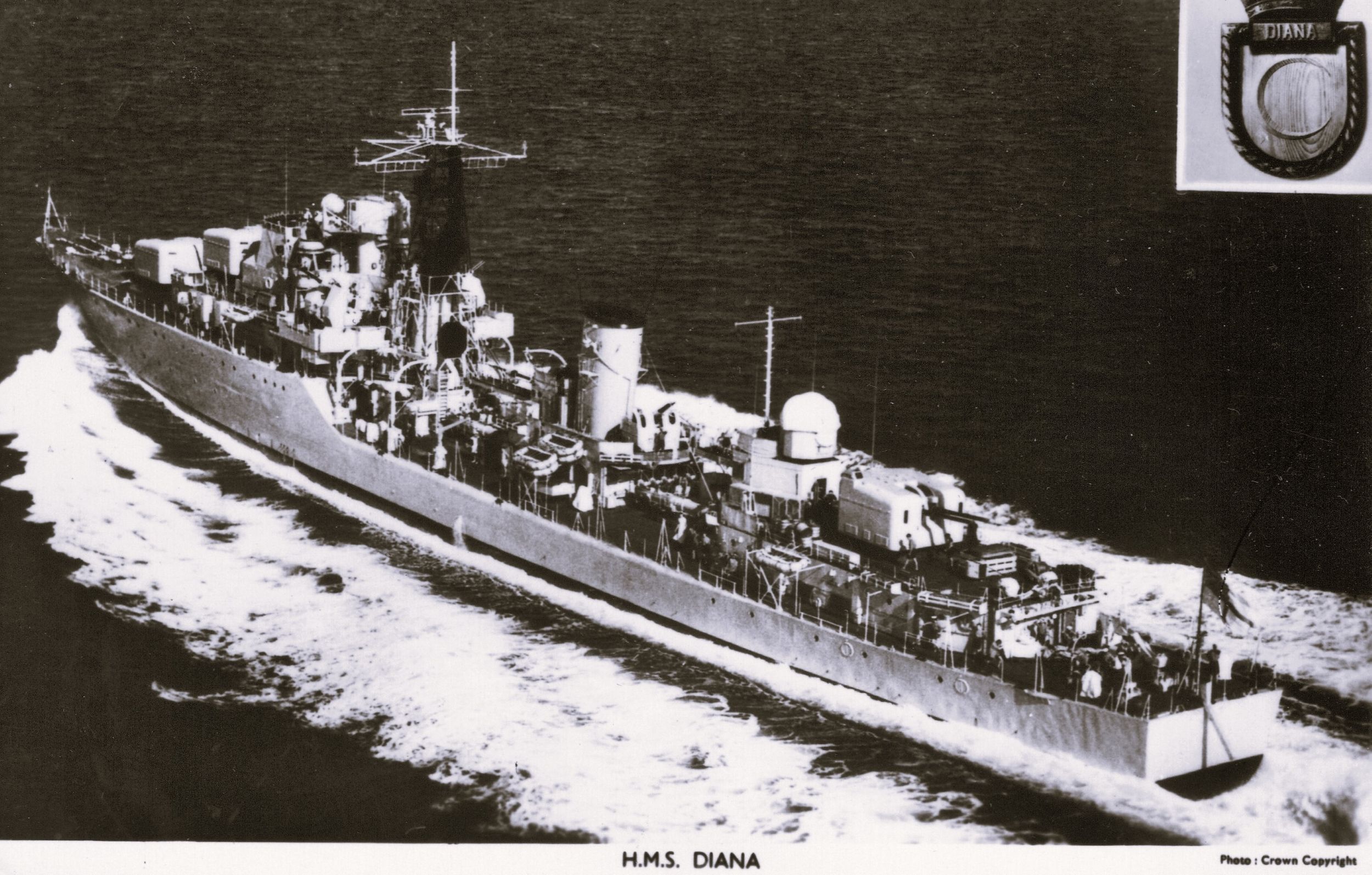

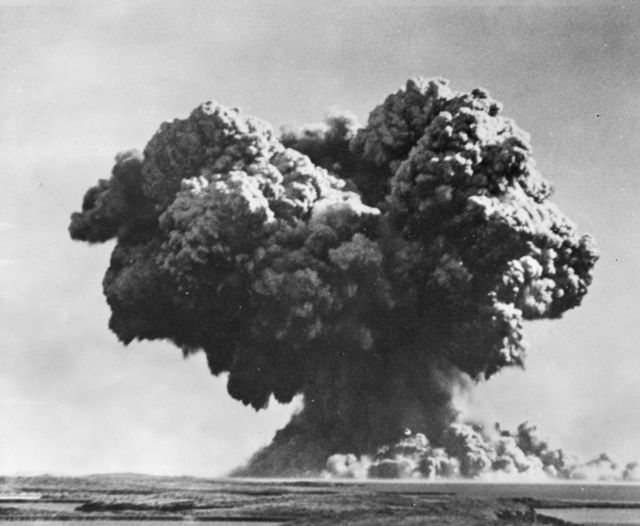

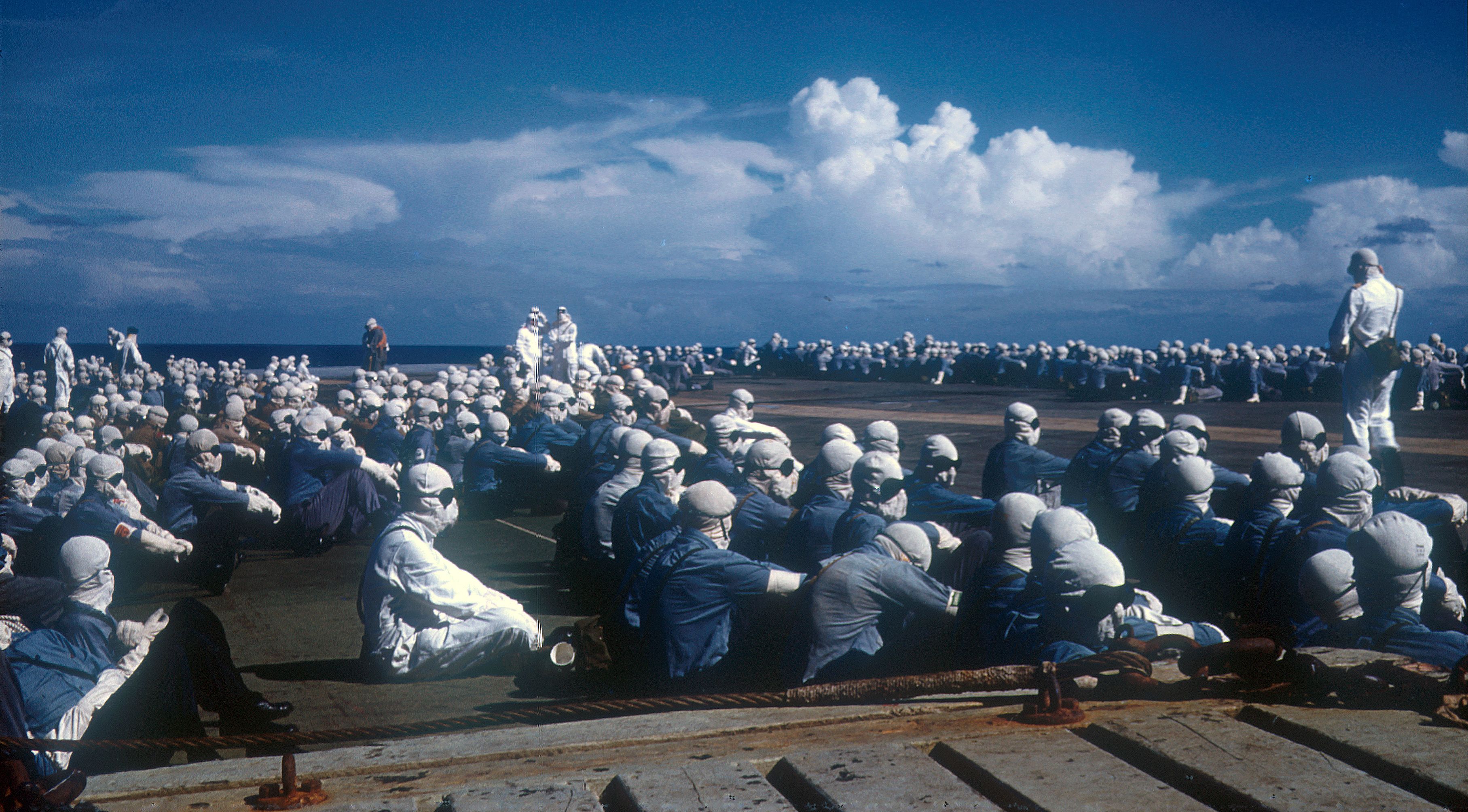

We wandered our way through the Panama, across the Pacific, and that’s when we found out we were going to Christmas Island. But in those days the Ministry of Defence had always sent the navy ships to Hawaii where they did the bombs. This time they decided to keep everybody there. And when we got there, we had what we call, they called them white crews in those days, they were British crews, they were tough nuts, they really were, and when they got there and found out they were doing the H-bomb we nearly had a mutiny on board. And the resident naval officer had to come out and chat to everybody saying it’s quite safe, nothing will happen, blah, blah, and all this sort of thing. Although we’re RFA and under the blue ensign, and flying by the MoD, we were primarily mostly navy civilians, that’s what we are. But the thinking at the time, they did this in Japan, why are they doing it now? You know. But the resident naval officer seemed to think, you know, try and encourage us to be trustworthy, and nothing will happen. And he gave us all these measurement metres, dosimeters I think they call them, which we put in our pockets, and we were all allocated certain jobs. And my job, I was sent down below at the time, to look after crew in case anything happened down there. I think it was by the engine room, I seem to remember. And we were all scattered around the ship doing our various jobs, and we had a countdown for this bomb, it was five, four, three, two, one, and I remember seeing a bit of a flash in the skylights, and I remember the bang, it was like standing next to a four-inch gun, actually, without earplugs.

Wow.

And like a miniature hurricane come rushing through, you heard it. The door, we had to keep the doors open, but you could feel this wind coming through. And afterwards you were allowed up on deck to see this mushroom cloud type cloud. We had, we weren’t allowed to take photographs, all the cameras were taken off us.

[ends at 0:01:48]