Arthur Matthews was born in 1937 near Portsmouth. He was recruited and trained by the Royal Air Force (RAF) as a radar mechanic at the age of 14. After his training Matthews became part of 76 Squadron and was stationed on Christmas Island for the Grapple Z series in 1958. He was later stationed in Malta where he was involved in monitoring French nuclear testing in 1960. He married in 1965 and has a son and a daughter. Matthews has undertaken a variety of work since leaving the military, including renovating houses and engineering work. He currently lives near Montrose, Scotland.

Interview extracts

Description

Arthur Matthews was part of 76 Squadron during Grapple Z and was stationed on Christmas Island in 1958. He had been trained as a radar mechanic from the age of 14 since being recruited by the RAF. He is still friends with pilot Terry Hilliard, who is also featured in our collection, and in their interviews they both talked about the inconsistent safety precautions taken during the test series. In this clip Matthews describes in vivid detail the process of cleaning ‘sniffer planes’ – aircraft that had flown through radioactive mushroom clouds to collect samples – including the clothing he wore for the job.

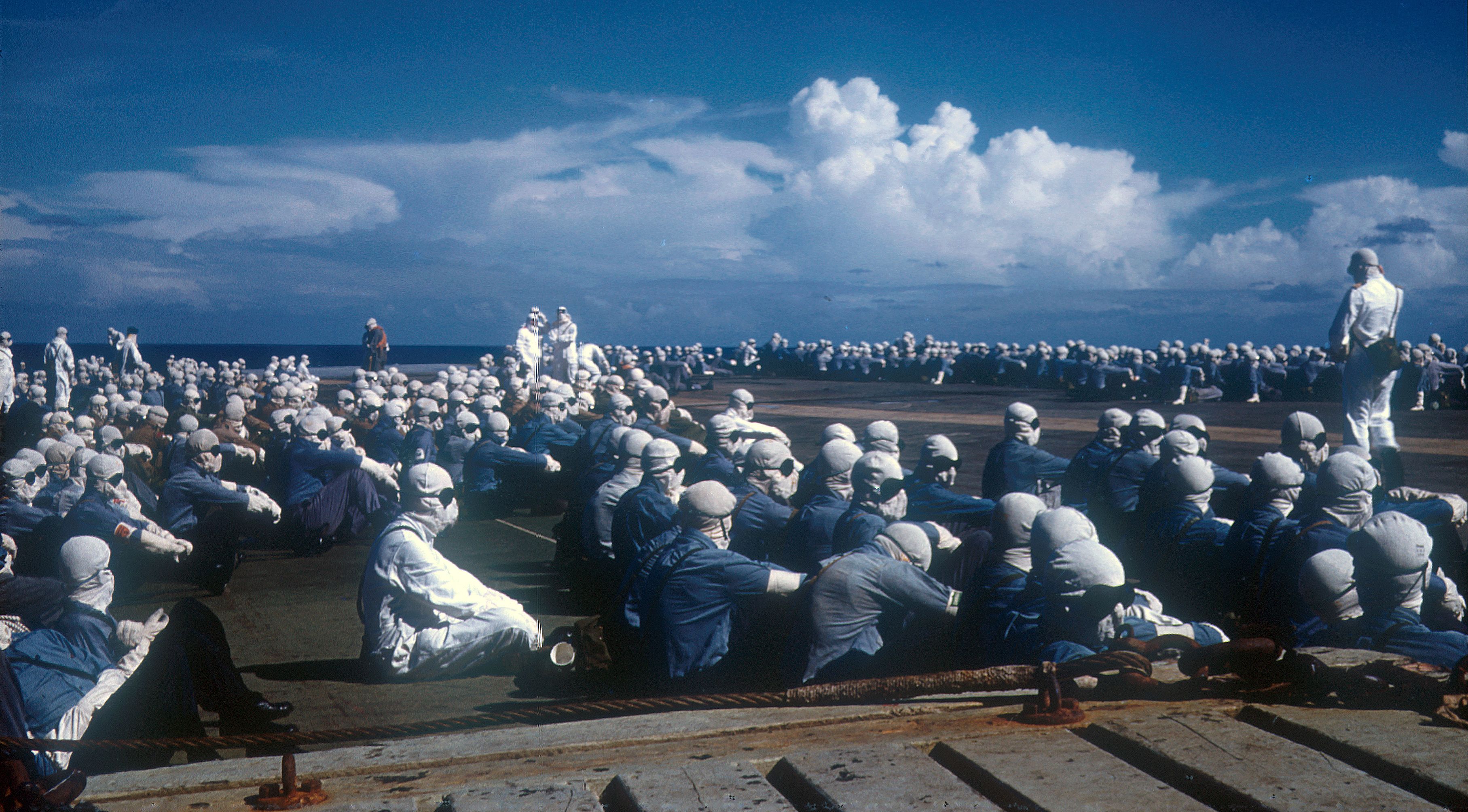

The photograph shows the runway on Christmas Island. During Operations Grapple and Dominic, the British and Americans buried high-grade radioactive waste under the runway, where it remains to this day.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Arthur Matthews was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Jonathan Hogg. This project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

When the aircraft came down and we got the crew out and got the samples out the wingtip into lead containers and that, then in turn we were stripped down and the aircraft was closed up and left for twenty-four or forty-eight hours, the half-life and that they left in the compound at the end of the runway. After a couple of days we’d go back in and put on all the gear again – and we were two degrees north of the equator and we had woollen underwear, the white suits, zip and double flap, we had surgical gloves, taped, thicker gloves over the top, taped, full mask, and you had to go out and wash them down, and with brushes remove all the emulsion. So we’re doing that and they’d time it. You were given twenty minutes at a time. That was considered, you were then… that was a bloody long time. You’d sweat and your boots, your wellington boots were taped, you had special socks and wellington boots taped to the thing, and you’re just filling up with your own sweat.

Yeah.

And then you come off, they strip you off, and somebody else will take your place and go out, until you got the aircraft washed down. After that they’d come back on the line, they’re back in use, no protective clothing, nothing, not even gloves. Nothing. Now, you might have washed off what was on the skin, but aircraft like that is a compressor continually working to pressurise aircraft up to a certain level, and the aircrew, their nitrogen in their suits, and they’re on a hundred per cent oxygen, so they’re not breathing any of this, so they’re okay, up to that point. But the inside of the aircraft, the hatches where we’d got our equipment and all that on the inside, that hasn’t been washed, that hasn’t been decontaminated. And on the apron, when we’re back in service, we used to go out. We had, all we had in the tent was a stand and a hand- you could put your hands in and get a reading. And we used to go out to the hatch, I remember seeing if the airframe mechanic, under the undercarriage, see what reading he’d get on his hand, and I’d go up in the hatch on top, see what I get. I was getting a huge reading, huge readings. And the aircraft were generally, they were dirty and that was it.

[ends at 0:02:51]