Derek Addy was born in Whitley Bay, Tyne and Wear, in 1936. He attended grammar school in the area and left school at 16 to work as a sales assistant in a department store. He was called up to National Service at the age of 18. He joined the Navy as an ordinary seaman. At 19 he was posted to Australia on HMS Diana for Operation Mosaic. Addy was responsible for ship maintenance on Diana. Following Mosaic, Addy spent the remainder of his two years’ National Service serving on the ship before returning to a career in retail. He has a son and two grandchildren and lives with his wife in Tyne and Wear.

Interview extracts

Description

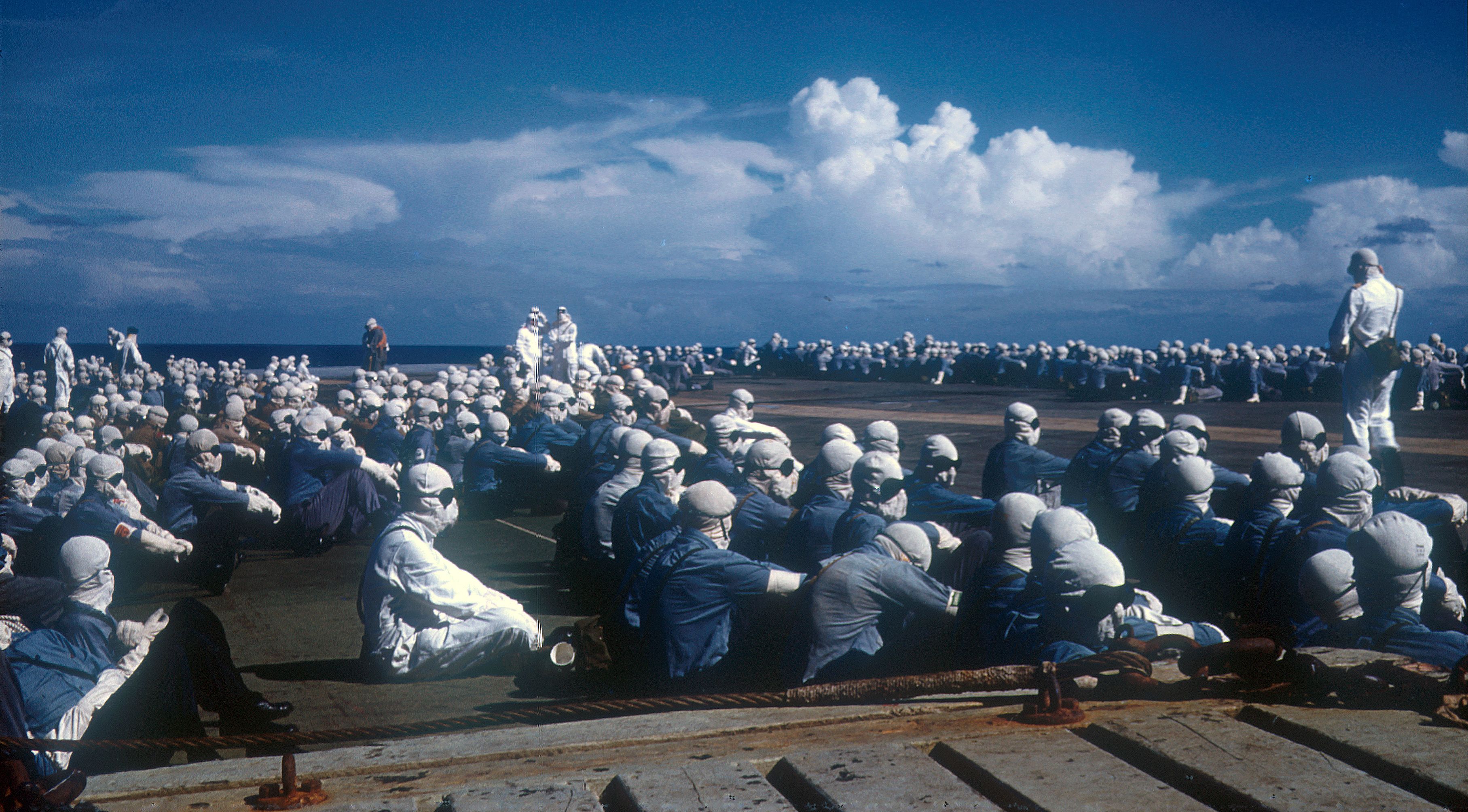

Derek Addy was admitted to a psychiatric ward at a hospital in Gosforth, Newcastle, in the 1980s. In this clip he describes the events that led to his admission, and his wife Anne’s impressions at the time. Addy attributes his psychological problems to his service in Operation Mosaic, where the ship on which he served, HMS Diana, was ordered to sail through radioactive plumes during two separate nuclear detonations. He recalls the experience of trying to mop-up contaminated seawater that had washed onto the deck of the ship.

These traumatic experiences were further underlined when HMS Diana engaged in a firefight with the Egyptian frigate, Domiat, during the Suez crisis. Addy vividly remembers looking through the gunner’s sight as burning men jumped from the Domiat into the water. Addy’s personal struggles in the 1980s may have been triggered by a pension tribunal in which he had to recount his experiences during Operation Mosaic. His appeal was ultimately rejected.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Derek Addy was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Joshua A Bushen. This project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

I was away with it, there’s no doubt about it, and I went into a psychiatric hospital for three days. Salkeld, obviously he was treating me, he was giving me tablets and all this business and everything else, and the guy who ran the psychiatric hospital in Gosforth in Newcastle, he got him to come to the house to see me, it was, you know, a big deal. He was a very, very important man, and Salkeld got him to come to my house to talk to me about it and he agreed I was away with the mixer. And they took me, and I was only in three days, that was all, I was only in three days, and the first day, there was something about the meals. The first day I think you had to have your meals on the ward or something like that, but after that, they said I was okay, I could go to the canteen and everything. I was only in three days, but I was in a psychiatric ward. Well, as I say, I thought I was doing my job alright. Anne said I was really away with it. She said when people used to come to talk to me and everything else they couldn’t believe the stuff I was coming out with. I always put it down to the bomb, I did. It was the bombs and the Domiat and one thing and another. Oh yeah. You know, when you look back at it, I mean the idea of sailing around in the fallout of, as I say, two atom bombs. And that’s all we had, we had sprinklers on deck, we had hoses on deck with holes punched in them, and it was contaminated seawater, was being pumped over the deck. That was what we had to protect us, you know? And then, you know, you read a lot about these things. I mean there were a lot of articles about it later on, the different newspapers and things interviewing people and whatnot, and talking about it and everything else. It had brought it, you know, brought it all back. I went to a tribunal in Middlesbrough, some time in the eighties, because I felt that, you know, that was what had caused my breakdown and everything. And I went to this tribunal, I mean there were a lot of people there, there were a lot of people there, and I got interviewed, you know, I don’t know who the hell they all were, all in civvies, but I had, you know, I had to go up and talk to all these people and everything, describe the experiences and everything else. And at the end of the day I got nothing from it at all. I felt, as I say, I felt that it was the bombs that had got me the way I was.

[ends at 0:02:27]