Gordon Coggon was born in Epworth Turbary, Lincolnshire, in 1938. His parents were farmers, and he was the eldest of 11 children. Coggon attended a local state school where he completed his O levels. After leaving school at the age of 15, Coggon worked as a deckhand on a trawler and as a topman on a drilling rig. He joined the Royal Air Force for his National Service. After his training, Coggon was posted to Christmas Island as an administrative orderly, taking on many different jobs on the island. Upon returning to the UK, Coggon signed up for a further 22 years in the RAF and was remustered as a crash rescue fireman, serving at home and abroad. He currently lives in Doncaster, Yorkshire, with his wife. Gordon has three children.

Interview extracts

Description

Gordon Coggon joined the Royal Air Force for his National Service. He worked as an administrative orderly during Operation Grapple in 1958, taking on many different jobs on Christmas Island. Here, he describes some of the hazards involved when fishing for sharks. He was also blinded for two weeks by the second bomb test that he witnessed. Upon returning home, Coggon signed up for a further 22 years in the RAF and worked mainly as a crash rescue fireman.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Gordon Coggon was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Jonathan Hogg. This project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

Yeah, I went fishing there and I caught a shark, me and my mate, and it pulled me into the coral and cut all my chest, before we managed to land it. But [laughs], I went to sick quarters that night because I’d been lacerated, and I got coral poisoning from it, and while I was in there, they were bringing senior NCOs, the old guys, instructors and whatever they were, from the sergeants’ mess into the sickbays. And they were playing hell, they were going to kill the bloke who took that shark to the sergeants’ mess because they’d eaten it and got food poisoning. They were drinking milk all night.

[ends at 0:00:53]

Description

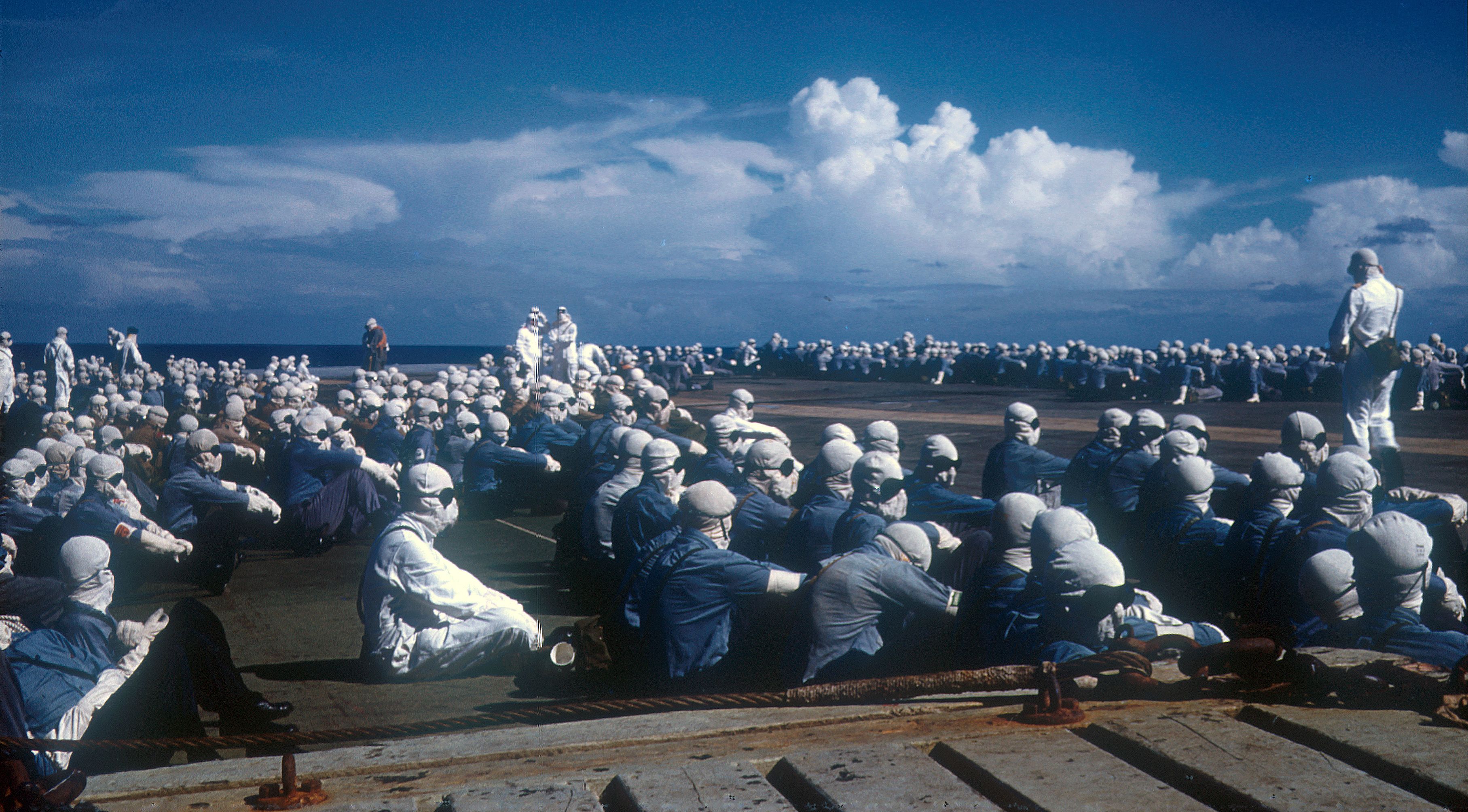

Gordon Coggon was posted to Christmas Island as an administrative orderly. He was present for a nuclear detonation as part of the Operation Grapple test series and describes the devastating effects of the bomb on local wildlife. He also talks about how the servicemen responded to this event, and the clothing that they wore to clean the area.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Gordon Coggon was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Jonathan Hogg. This project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

Later on, we noticed loads of birds had fell out of the sky and they’d been blinded. There was fish, the following morning, not the same day, the following morning, literally thousands of fish on the tideline. We had to pick all them up.

Before the test, you said you were quite worried about what could happen. So how did you feel then when you saw all the fish and the birds that had been injured like that?

Oh, I was upset. I was upset. I thought, well, if they’ve been killed, we could have easily been killed, you know. I was upset more from the fact of the unknown more than anything else. I didn’t know they was irradiated at the time. The fish was. The birds were just blinded, they couldn’t see and they fell t’ground, you know. It was terrible, oh. When we reported it, they said, stay away from them. And then they got, the officer had got several of us, I remember, to go out. There was more than several – half the camp – but I was in a party of several with an officer and the officers were in their white suits and we were in shorts and shirts. They give us gloves. That was it.

[ends at 0:01:46]

Description

Gordon Coggon discusses how his experiences at nuclear test sites have stuck with him and the nightmares he has had. While on Christmas Island, he suffered with heart problems and since returning home has faced other issues. His family have also possibly been affected, and these experiences have left Coggon with significant anxiety around his health.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Gordon Coggon was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Jonathan Hogg. The project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

It’s something you’re never ever going to forget, no matter how long you live, I’d never want to see it again, ever. It frightens me just thinking about it. In fact, sometimes I wake up, my wife, it frightens her, because when I wake up in the half-stupor, I’m screaming and saying ‘I’m lost, I’m lost, I’m lost’. And she’s saying, ‘Where are you lost?’ and I’m saying, ‘I’m lost in the fog, I’m lost in the fog’. And I can’t get it out of my head that I’m lost in this fiery fog. Still, to this day I have the odd dream. Not so often now, but it was at one stage quite often.

[ends at 0:00:53]

Description

Gordon Coggon was blinded for two weeks by the second bomb test that he witnessed. In this clip, he argues for the importance of educating young people about the legacies of nuclear weapons testing. He mentions LABRATS (Legacy of the Atomic Bomb, Recognition for Atomic Test Survivors), a nuclear test veteran support group.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Gordon Coggon was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Jonathan Hogg. The project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

I’d like to see in history in black and white and for the MoD to admit what they did, or to be forced to tell the true story behind what they did. You know, for it all to come out like you’re doing now, all to come out in the open and show people that we was used as guinea pigs, and we were. That’s what I want. I’m not interested in the bloody money, they can keep it as far as I’m concerned, I’m more interested in the kids’ future health. That’s why I’ve done things like the book, I’ve donated it to LABRATS so they can help other bomb victims, specially children, now. I mean I’m not well off, but I’m not downcast either, I’m quite happy, financial situation, it’s a bit hard sometimes, but apart from that, I’m okay.

[ends at 0:01:10]