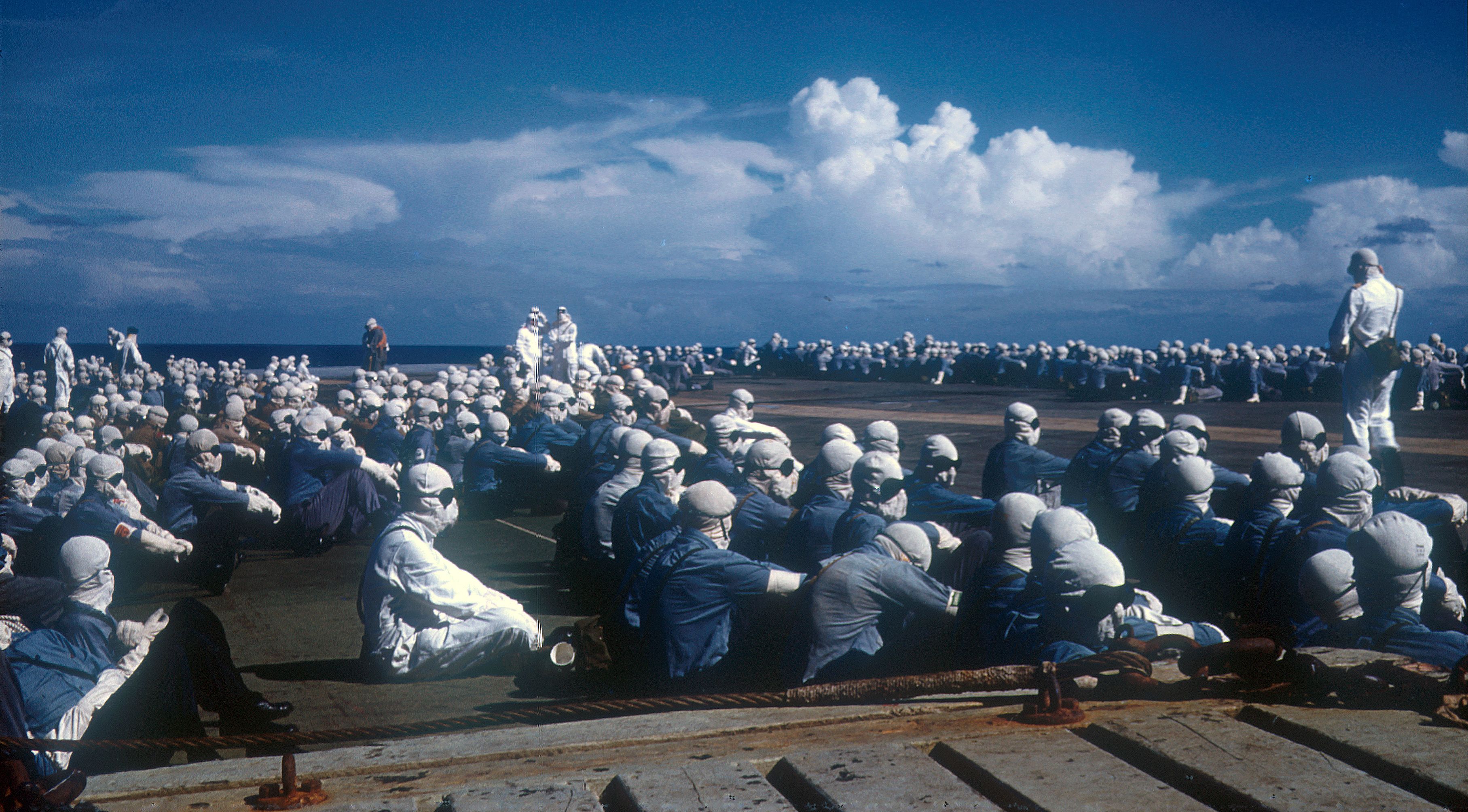

John Morris was born in Liverpool in 1937. His father was a labourer and his mother worked as a crane driver. Morris grew up in the village of Little Lever, in Bolton, where he attended school. Upon leaving at the age of 15, he worked as a paper maker before being called up for National Service at the age of 18. He joined the Army and was posted to Christmas Island for Operation Grapple. On the island Morris worked in the laundry and served there for a total of 16 months. After completing his National Service he worked for Prudential plc. He has three children and currently lives in Rochdale.

Interview extracts

Description

John Morris was born in 1937. As part of his National Service, he was assigned to the Royal Army Ordinance Corps and contributed to the Operation Grapple nuclear test series on Christmas Island. In this clip he compares his memories of witnessing a nuclear detonation with the depiction of the atomic explosion in Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer (2023). He also mentions the scale of the explosion he witnessed in relation to Hiroshima. In recent years Morris has been at the forefront of many campaigns organised by LABRATS (Legacy of the Atomic Bomb, Recognition for Atomic Test Survivors). At a recent reunion, veterans were invited to watch Oppenheimer together.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. John Morris was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Jonathan Hogg. This project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

An atomic bomb was like a firework, because it, the devastation of an atomic bomb is something that, like I’ve earlier said, it’s almost impossible to describe. Anybody that’s watched the film, Oppenheimer, that film, I went to see that film, and I, it took me back to being eighteen. I often wondered, when I tell the tale about the atomic explosion, were I embroidering it, were I making it bigger than life, was I making it, were I making it up? Is it too, too, too unreal? But trust me, what I saw, and veterans like me, saw and felt was as dreadful as that explosion was in Oppenheimer. And mine, I said earlier, I was twenty miles away from the last explosion, and that was a hundred times greater than Hiroshima, but I was twenty miles away. I had a pair of shorts on, a shirt, and a pair of sunglasses. Now, if anybody said today, I’d like you to go and sit twenty miles from the centre of the sun, you’d soon tell me where to go. I was ordered. I’d no choice, I had to do what I was told.

[ends at 0:01:40]

Description

John Morris describes his feelings on playing a part in the creation of the British nuclear deterrent. After participating in Operation Grapple, Morris and his family have suffered significant health complications. Due to this, he has become a strong advocate for compensation of veterans and nuclear disarmament.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. John Morris was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Jonathan Hogg. The project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

My desire over sixty-three years to get recognition for the veteran, for what we did for this country, we made this country a nuclear power. I regret many times being involved in it. I created or helped to create a monster, and it does weigh heavily, what the monster that I’ve helped make. And it’s, it makes me sad sometimes that somebody could throw one of those bombs, and trust me, you haven’t got a cat in hell’s chance. You might as well give up, because it’ll completely destroy you. And it’s had a profound effect on some of my thoughts. And you do get flashbacks, you do, you do get… you look at your grandchildren, you think, I hope some bugger doesn’t start throwing one of these about, because they’ve no chance.

[ends at 0:01:14]

Description

John Morris describes the tragic circumstances in which he and his wife Betty lost their baby son, Steven, and the conflicting statements they received regarding the cause of death. The parents were only granted full access to the autopsy report 50 years later. The report stated that Steven’s lungs had not properly formed. Morris and his family believe that Steven’s death and the deaths of other veterans’ children were linked to their involvement in British nuclear weapons tests. Morris has been a leading figure in LABRATS (Legacy of the Atomic Bomb, Recognition for Atomic Test Survivors). In June 2022, he met with Prime Minister Boris Johnson and demanded a medal on behalf of the organisation during its ‘look me in the eye’ campaign.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. John Morris was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Jonathan Hogg. This project was in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

As I said earlier, I did a seminar in Manchester. There were twelve men, and all of us, I’d lost, I lost a son, a cot death. I was arrested, me and my wife were arrested, saying that we’d possibly killed him. We put him to bed at night, we got up in the morning and he were dead in his cot. Got to hospital, the police came and, okay, they’ve got to do that, they’d no option, you know. Then, three days later, they said oh, we’re not pursuing any charges, it’s a cot death. When we got the death certificate it was bronchial pneumonia, so it started murder, then a cot death, then bronchial pneumonia. And it took me fifty years to get an autopsy report. They wouldn’t release the autopsy report. The autopsy report says that his lungs hadn’t formed correctly. Was that part of the atomic bomb? There are hundreds – and researchers can look it up – there are hundreds of us gone the same way. Lost children, had children with huge problems, some a lot worse than me. I had three children after, all of them are okay, apart from my two daughters. My other daughter had two miscarriages, and the last one they said, we would advise you, Kay, not to have any more children. They wouldn’t tell her why, other than the baby wasn’t, it wasn’t growing as it should, but they wouldn’t go into any detail. Now, is that part of the inheritance that we’ve given? That much I don’t know. But again, when you talk to the veterans, there are hundreds of us gone through the same routine.

[ends at 0:02:08]

Description

While discussing remembrance, John Morris describes wanting the same recognition for nuclear test veterans that war veterans receive. Morris was significantly impacted by his experiences on Christmas Island. Both he and his family have suffered numerous health complications that he attributes to his service during Operation Grapple. He has been an active campaigner for the nuclear test veteran community and appeared in the BBC documentary Britain’s Nuclear Bomb Scandal.

British nuclear test veterans are not the only cohort of ex-servicemen who have had to wait decades for medallic recognition. Servicemen who participated in the Arctic Convoys during the Second World War were not permitted to apply for their medal, the Arctic Star, until 2012. The ‘Bevin Boys’, young men conscripted to work in the coal mines between 1943 and 1948, also had to wait before being recognised with an official badge.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. John Morris was interviewed for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Jonathan Hogg. The project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

I felt very, very strongly that I deserved recognition for what I’d done for this country, similar to what the soldiers in the First and Second World War had done. They were recognised for their valour and what they’d done for this country. I believe that the atomic veterans deserve the same recognition. And finally, we won. Finally. But it took a lot of time, a lot of money – it’s all self-funded. Not that it bothered me, because I have principles, and that principle was very, very strong in me for people that are no longer here to fight for themselves, or are not capable of fighting for themselves. And that’s why I think this sort of history needs to be out there. And people, in time to come, as they often do, to look back in that history and to learn from it.

[ends at 0:01:17]