Photo © Alan Rimmer, used with permission.

Ken McGinley was born in Johnstone, Scotland, in 1938. He had five brothers and two sisters and attended St Margaret’s Roman Catholic School. After leaving school at 15, McGinley worked as a bank boy and then a van boy. At 18, he joined the Army and was posted first to Ripon, Yorkshire and then Osnabrück in Germany. In 1958 McGinley was posted to Christmas Island, where he witnessed the Operation Grapple testing series. After returning from the island, he suffered from several health conditions which led to his medical discharge from the Army at the age of 21, after which he worked as a bookkeeper and ran a bed and breakfast hotel. He married Alice in 1960 and together they have a daughter, Louise. In 1983 McGinley founded the British Nuclear Test Veterans Association and served as the Association’s chairman until 2000. He died in June 2024 in Johnstone.

Interview extracts

Description

Ken McGinley grew up in Johnstone, Renfrewshire, Scotland. In this clip he reflects on the scale of recruitment in his hometown for National Service on Christmas Island. McGinley, who carried out his service in the Royal Engineers, later began to suspect that these recruitment figures were disproportionate. After writing an article about the subject for the Sunday Post, he was called before the Scottish government in Holyrood to give evidence. McGinley was the founding chair of the British Nuclear Test Veterans Association.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Ken McGinley was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Christopher R Hill. This project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

The thing about living in Johnstone, everybody knew each other. This is the amazing thing. And, you know, it’s like, we were talking about, you know, Celtic football team, about when they won the European Cup, they all lived within twenty mile of each other. When I went to Christmas Island and did research and all my, looking through all my records and one thing and another, I discovered there were twenty or twenty-one lads that were born in Johnstone. Six of us went to the same class, five of us worked for the same company, and yet there was only less than twenty people worked for that company, went to Christmas Island. And I did the article when I read this research and I couldnae believe it, you know, Tony Crampsey, Pat Haggerty, Frank Murney, Jim McGlynn, John Ferns. You know, I looked at them all and I says, my God, big Jim McBride, we all went to church together too, and things like that, you know, and met each other every day down the street, and we all lived within a square mile of each other. I was saying, so what the hell’s going on here. So I’m looking at that and I’m saying, right, so I did a story in The Sunday Post and it was so effective that the Scottish government took it up.

[ends at 0:01:37]

Description

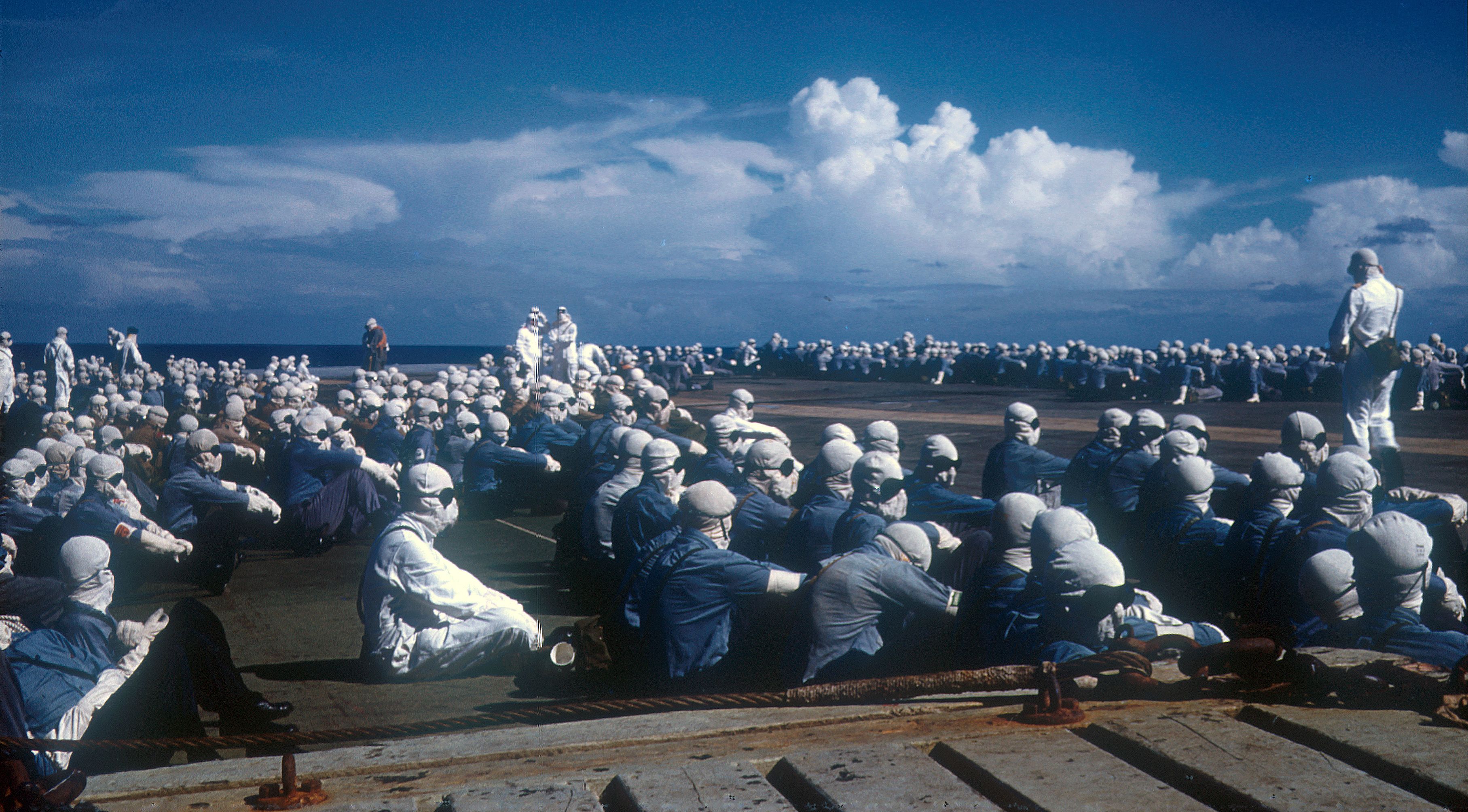

Ken McGinley describes wives and children arriving on Christmas Island in 1958 on HMT Dunera. Having paid £25 for the privilege, they were brought over to the atoll with fresh troops to boost morale following the successful detonation of Grapple X. After a week of sightseeing, the 30 wives and 31 children set sail back to the UK with their fathers, who had completed their duration of service. Not long after returning home, the wives and children began to experience ill-health conditions. One mother reported how her six-month old daughter began to lose her hair. The family doctor could not identify the cause.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Ken McGinley was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Christopher R. Hill. This project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

What shocked me more than anything else was, all of a sudden, coming off the landing crafts, were children and women. White women and white children.

Oh, right. Coming on to Christmas Island?

Aye. From the ship, from the Dunera. Yeah. I says, what the hell’s going on here, I thought, what are they doing on the island, you know? These were the men who were on the island who were being relieved, and they were going back on the ship with their wives and children.

Why?

But, who in their right mind would send children and wives to an island that just had detonated a bomb, a hydrogen bomb, Grapple X, in November 1957.

So, when you’re arriving then, these women and children are getting off the boat, this is, how long did it take for the Dunera to get from the UK to Christmas Island?

Round about four weeks.

Right, so you’re there by the end of January, February?

We never saw these women and children because there were different decks, you see?

Yes, and that’s 1958, so only three bombs as part of the test operation, Operation Grapple, had been conducted so far, and that was one, two and three on Malden Island?

Yeah, the three tests that were conducted in Malden Island were allegedly hydrogen bombs, but they were false bombs, they were false, only largely 880,000-ton atomic bombs, you might say. But this was all done with the Americans, you know.

[ends at 0:01:52]

Description

Ken McGinley discusses the controversy over whether it rained on Christmas Island after Grapple Y, Britain’s largest ever nuclear test. McGinley describes experiencing a rainstorm after the detonation as a relief from the humid conditions. He also refers to a conflicting statement from the Ministry of Defence. McGinley and other veterans believe that exposure to the rain was connected to ill-health in later life, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Several veterans also believe that the air drop detonation may have gone awry, exploding closer to the ocean and the south-east point of the atoll than was planned.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Ken McGinley was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Christopher R Hill. This project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

Yeah. During Grapple?

Aye. Grapple Y, aye.

So, I mean it’s all leading up to that first test, because that was Britain’s biggest ever bomb, wasn’t it, Grapple Y?

My analysis on it, that I found that the cases of leukaemia, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, were mainly attributable to Port London. It did rain that day, and Alan just sent me a, Alan just brought over new information there about Lord Penney telling you how a nuclear bomb can start a thunderstorm. I’ve got the documents here on it. He just brought me that over yesterday.

There are atmospheric physicists at Reading today are looking at weather formations using historical Met data based on rain patterns coinciding with nuclear tests in the fifties and sixties.

That’s right, yeah. Although they say, the Ministry of Defence have always maintained it never rained. But I’m sorry, you’re liars, for the simple reason being, I was there. I walked back – and another thing, which you’ll never hear from a nuclear veteran – when we were walking back to the tent, I told you there was two men standing at the side with their white, all their whites on, with masks on, goggles on, and they shouted ‘Get under cover, get under cover’, that’s when it started to rain. And it was like… and originally, or initially, it was actually like big droplets, and then it just come down, the rain. We were taking off our whites to throw into a big bundle, they told us, put your white gear in that bundle there, so you just took it off and threw it in a bundle. So we took it off, threw it in a bundle, walked back to the tent. These guys were saying, ‘Get under cover, get under cover’. No way, we were standing in that heat for about three hours and that rain was just lovely and cool, you know. Didnae think, radiation or anything like that, or didn’t even know what radiation was. I don’t how we could have spelt it in those days even. But, walking back down to the tent, we were doing… Alan, myself, Billy Pettigrew, I think it was, we got a can of beer each and sat outside the tent drinking it and just, we never spoke, we just kind of looked at each other. What do you think of that, eh? Don’t know.

And you think, looking back on it, that there were more lymphomas for people in Port London as opposed to main camp?

Yes.

Is that because of the rainout from the test?

I would think it was from the rainout, aye. You see, this is what I was leading up to. After we had our beer, it was just about lunchtime, so we went up to the canteen, we were standing in the queue with our mugs, waiting for our – your knife, fork and spoon in your mug – standing in the queue. And this guy’s coming round with a ladle and a bucket. We said, what the hell’s that he’s putting… it was navy rum. Because we served under HMS Resolution, although the camp commander was Major Hubble, lovely big man. So, oh, we’re getting a tot of rum. I’d never tasted rum before, so drank it. Ugh! Drank it all anyway. Then we had our lunch. Says to the guy that was dishing it out, ‘Why are we getting the rum?’ He says, ‘Because it’s traditional in the navy, every time it rains, we issue rum’. So that would have went on HMS Resolution’s manifest, you know. So, you know, so that night, that night it was, oh, the toilet. You couldnae get into the toilet that night. Stomach, and I says, ‘Should never have drunk that rum’. That nausea feeling I had, and diarrhoea. I didn’t know whether to be sick or have diarrhoea. You’re sitting on a pan, making all kind of funny noises. And at the same time, you’re urgh, like that, you know. So, didnae know what to think. [00:04:58] About two days later, I was in a tent, and I woke up, I couldnae open my eyes, God’s sake. I went out of the tent, to the flagpole, and there was a wee mirror there, and I had kind of water blisters under here, down here, on my neck, and just on my chest. And I’m trying to squeeze them out and that, and I couldnae. They weren’t painful either, you know. So I says, I need to go to the doctor, see what’s wrong here. So I went along to the doctor and there was loads of guys there with blisters and, you know, just various types of skin things and that, you know. And he was putting a solution on us and that was it. But it cleared up after a few days. Left me a bit scarred, right enough. And, never thought anything about it at all.

At what point did you think the fact that we were, the fact that it rained after Grapple Y is problematic for us because it could have exposed us to radioactive fallout, when did that occur to you? Presumably once you were back and years later?

Oh aye, years later, you know. Because we always maintained, everybody that took part in the test say that, quite clearly. Oh, it rained that day just after the test, you know. And yet the Ministry of Defence said there was no rain on Christmas Island that day, you know. What? The bloody water was running down the roads. They’ve got it in film, you know.

Yeah. And that’s what the Dispatches programme was about.

Exactly. So, you know, this is what, so there’s lies, you know. At the Ministry of Defence you’ve got, you had good liars and bad liars, you know? That was the problem, you know.

[ends at 0:07:07]

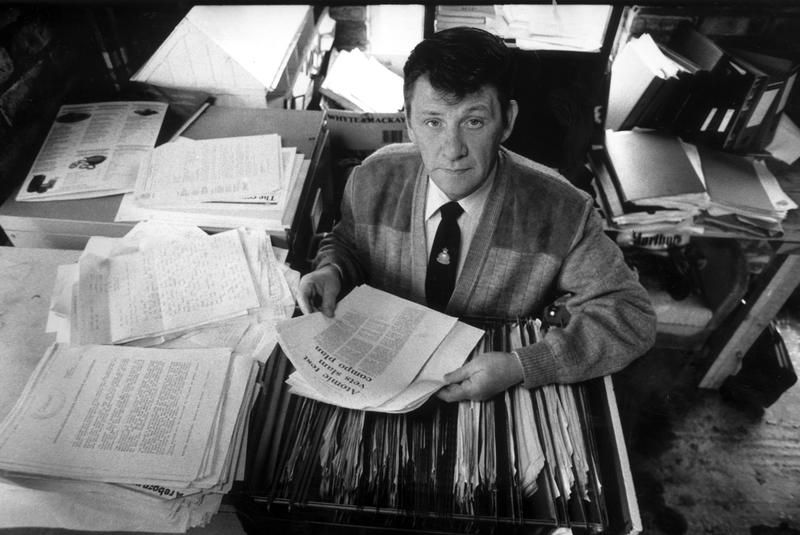

Description

Ken McGinley discusses the public impact of his article in the Daily Record, which led to further local, national and international news coverage on the ill-health of British nuclear test veterans. Ultimately, this publicity created the conditions in which a national organisation could be formed. McGinley reflects on his role in the founding and naming of this organisation, which became known as the British Nuclear Test Veterans Association (BNTVA). McGinley became the first chair of the BNTVA in 1983, a post he held for over 15 years. He was prolific in collating evidence about British nuclear test veterans’ health conditions and was a constant thorn in the side of the Ministry of Defence.

The photograph shows McGinley speaking at a press conference in Japan. As BNTVA chair, he supported campaigns for nuclear justice worldwide, including in the Ukraine and Russia after the Chernobyl disaster of 1986. In Japan, he achieved minor celebrity as the face of a Japanese brand of Scottish porridge oats. In his interview, he recalled a photograph of himself being accompanied by a caption to the following effect: ‘If the oats are good enough for Scottish hibakusha [bomb-affected people], then they should be good enough for us in Japan’.

At the end of his oral history interview, McGinley wryly pondered how much money he had been able to extract from the UK government on behalf of veterans and their families. Having granted the interview whilst living with stage 4 cancer, McGinley sadly passed away only months after the interview was conducted. His courage, humour and lucidity during the recordings are indicative of the great character he demonstrated throughout his leadership of the BNTVA.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Ken McGinley was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Christopher R Hill. The project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

You’ve got to remember that in November 1982, after I did that article in The Daily Record, what happened was it went from local to national, to international. It went worldwide actually, you know. And before we knew where we were, there were interviews with radio, television. At that time Nationwide had taken it up, BBC had taken it up, STV had taken it up, and I had a great relationship with everybody, especially with Nationwide, because I was in touch with Dr Alice Stewart at Birmingham University because she was doing a lot of research at the time, people were sending in information to her, into Nationwide, and it was all going very, very well.

Alice Stewart was a leading radiobiologist?

Yeah.

Right.

She was a fantastic person. So we decided, when it was all coming to fruition, you might say we were getting things all together, everything was going well, and we decided to hold a meeting down with this other guy who – Tom Armstrong – who was another one who made a claim. So we had a meeting in – this is how the BNTVA were formed – we had a meeting on 5th May 1983 at Birmingham University. People present were Philip Mun, Ken McGinley, Dr Alice Stewart, Dr Tom Sorahan and Tom Armstrong. So there was only five people at that meeting when the Association was founded and named that day. We agreed on, some were saying the British Atomic Veterans, and I says this is going to be a long name, but I would just say British Nuclear Test Veterans Association. That’s the one we’ll have.

[ends at 0:02:19]

Image at the top of the page: Ken McGinley surrounded by documents in his fight for justice on behalf of British nuclear test veterans. Photo © Alan Rimmer, used with permission.