Robert James was born in Bedford in 1937 and grew up in Portsmouth. He was evacuated to the Isle of Wight during the Second World War. After joining the Royal Air Force (RAF) and receiving further training as a firefighter, he was posted to Maralinga for Operation Antler in 1957. He signed up to stay in the military and his career included postings to the Vietnamese and Cambodian border, as well as to Yemen, Ireland, and Cornwall. He also travelled to work in Saudi Arabia before his retirement. James later became involved in nuclear charities and campaign groups. In 2024, James visited Kazakhstan to take part in a Nuclear Survivors Forum, organised by several groups including the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN).

Interview extracts

Description

After joining the RAF and receiving further training as a firefighter Robert James was posted to Maralinga for Operation Antler in 1957. In this clip he talks about the dangerous work involved in putting out an irradiated airplane. Later in life, James became involved in nuclear charities and campaign groups. In 2024, he visited Kazakhstan to take part in a Nuclear Survivors Forum, organised by a number of groups including the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN).

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Robert James was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Joshua Bushen. This project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

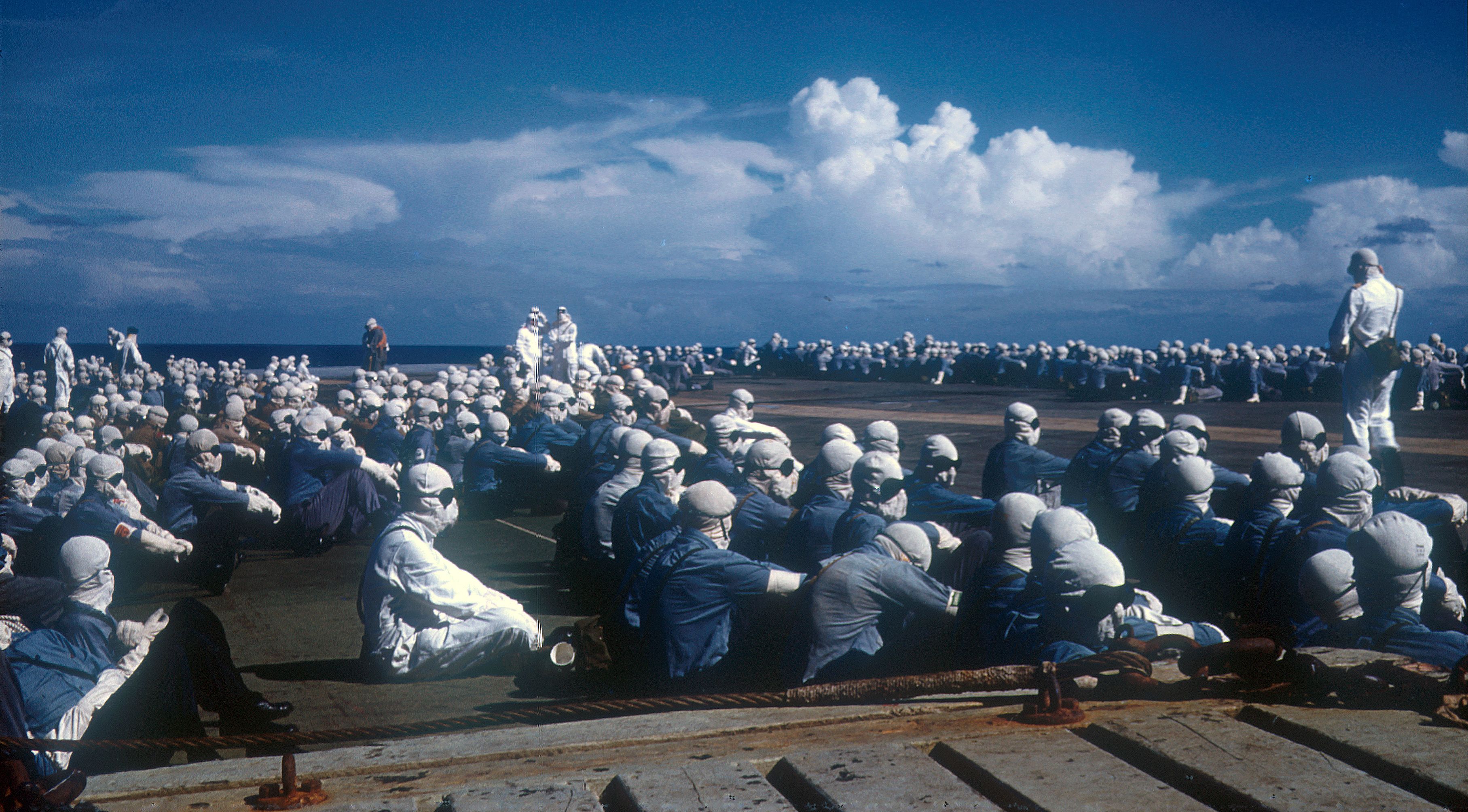

We did have… we had no protective clothing against radiation at all, none of us did. Nobody on the airfield, not even the officers, nobody did. The only people that had protective clothing was the scientists when a few days after each test they would go [inaud 00:14] area with the Geiger counters and what have you. But we did have, quite often when there was a test, aircraft would fly up through the cloud getting samples. And of course, when the aircraft came back, they were full of, giving off radiation, alpha and beta rays. Amongst other things, one thing I remember, we had a V bomber coming in, it was a Valiant, and nearly overshot the runway, and of course he braked hard and all the undercarriage was on fire. And with aircraft undercarriage, a lot of the metals are made with metals that burn and produce their own oxygen, like zinc, magnesium. And of course, putting those fires out is difficult. We had water, foam and carbon, CO2 gas, right? CO2 gas is freezing, it’s good for smothering, but we couldn’t use it, because it would have caused it to disintegrate and explode, because it’s freezing cold on red hot metal, it would just explode. So we had to spray, not foam, but to spray water slowly over the undercarriage. We were right underneath. But of course, while we were doing that, we done that satisfactory, took about half an hour to really cool it down, if not longer, it was giving off radiation.

Yes, so this was a plane that had just flown through the cloud, then land, catch fire, then you’re underneath it putting the fire out.

Yes, yeah.

Yeah.

And so we were absorbing radi… we didn’t know, we didn’t realise that we were. But we did, all of us got issued with a dosimeter for recording the amount of radiation, but in those days, it was a film badge.

Just, yeah.

There was a little holder with a film inside and it recorded the amount of rads or roentgens, the amount of rads your body’s absorbed. But they never told us what the readings were.

[ends at 0:02:12]