Terrence ‘Terry’ Hilliard was born in Newport, Monmouthshire, in 1932. One of seven siblings, he grew up in Portsmouth before being evacuated at the start of the Second World War. He attended a grammar school in Waterlooville in Hampshire and then joined the Royal Air Force as an aircraft apprentice aged 16. In 1952 he began his pilot training and joined No. 9 Squadron. Hilliard was posted to No. 76 Squadron in 1957 and shortly thereafter arrived in Australia for Operation Grapple, where he served as squadron pilot and acting flight commander. During the Operation Grapple Z3 detonation, Hilliard was the primary sample sniffer. For this role he flew his Canberra through the mushroom cloud to collect scientific samples. Hilliard stayed in the RAF until 1969, after which he and his family ran a small family hotel and Hilliard worked in insurance. The family moved to Australia in the 1980s where Hilliard worked in training, and later returned to Portsmouth where he still lives today. Hilliard and his wife Sally were married for 60 years before Sally’s death in 2018. He has three children, four grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren.

Interview extracts

Description

Terry Hilliard joined the RAF as an apprentice in 1947. During Operation Grapple he piloted a plane through a mushroom cloud to collect radioactive samples. In this clip he outlines the different stages of the cloud and the height it reached, as well as the black rain he witnessed at 55,000 feet. Cloud samplers like Hilliard have reported increased rates of cancer and other diseases, thought to be due to their exposure to radiation immediately after bomb detonations. Hilliard retired from the RAF aged 37.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Terry Hilliard was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Fiona Bowler. This project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

It goes up and you get a stem and the fireball, like a great big fireball, rises fairly fast. It’s through the troposphere, through the ionosphere and it aims up into the stratosphere, but I’m not sure how high it eventually goes, I think it stays in the stratosphere probably.

Yeah.

And the reactions are going on in the fireball.

Yeah.

What’s in the stem is history, that was what was happening minutes ago, of course. So that wasn’t what they wanted, they wanted what’s going now on the filters. So they wanted you as high as possible, if you could be, on the top of the fireball. I never got to the top of a fireball, I was at the bottom of a fireball. But that was enough. And of course, the turbulence, you can see in the photos on the films, all the clouds turning over, turmoil and so on. And trying to fly into that above your recognised speed and keep the crew pacified and then saying… and they had to open and do the shutters with a switch they had, because they used the electrics which ran the pumps in the tip tanks, the extra fuel tanks, which we took off, and the electrics which were out there, they rewired into the filters. So they had switches to open and close the filter things, and they had to open them at the right time and so on.

Yeah.

And the aim was, to get into the densest cloud you could find, because that was more active. But the densest cloud was also the most turbulent. And I came out of one and said, ‘Ooh, there’s a very black cloud just down there’, and I said it on the RT, ‘There’s a very black cloud just down below…’ ‘Don’t descend! Don’t descend! Climb! Climb!’ ‘Yes, yes, I’m climbing, I’m climbing.’ And they just shouted, ‘That’s probably just cirrus, forget it’. Because with all this reactivity going on, it’s forming its own cloud, its own weather, its own rain. One of the problems, they had pouring rain, purple rain, and then black rain. It was filthy, the black rain, at 55,000 feet. I mean it’s unheard of, the meteorologists would have a nightmare.

[ends at 0:02:25]

Description

Terry Hilliard, an RAF pilot who collected nuclear cloud samples during Operation Grapple, gives his views on the refusal of the UK government to compensate its nuclear test veterans. He refers to the case of Squadron Leader Terry Gledhill, who during Operation Grapple would assess the nuclear clouds before being the first to fly into them to gather samples. It was not until after Gledhill’s death in 2015 that his family started to get full access to his medical records, which have proven a turning point in the legal campaign against the UK government. The so-called ‘Gledhill memo’ has been particularly influential, as it suggests that the authorities may have hidden the results of blood tests carried out on British troops before and after tests. These results could have provided the data needed by veterans to understand their radiation exposure.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Terry Hilliard was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Fiona Bowler. The project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

I’ve got no aggro about the whole programme, but they should have, they did, they say they did do medical checks, but they won’t show us, they’re still secret. And Terry Gledhill’s daughter has been to court to get his documents, and they’ve approved, and the court have ordered, the thing, to send all his medical documents to his daughter. That came in yesterday. So that’s a huge step forward. So, some of us can probably get our medical records. But I must say, I’m getting to the stage, look, it’s seventy years ago, it won’t change my health now if I know or not, why cause all the angst, you know, do I really want to start fighting court battles at my age, you know? I’m not at all blaming the Air Force, they have their limitations, they did what they could within the limits, they just didn’t publicise it because… and it was top secret atomic, UK eyes only, they didn’t want the Russians to know what our bombs were like, they didn’t want to know whether we got doses because we didn’t want them to know, and the Chinese hadn’t yet done their bomb, or the French, or anyone else. Or the North Koreans, or the Indians, or the Pakistanis, who’ve all done it now. As I’m sure you know, we’re the only country that hasn’t given financial compensation, all the other countries have given compensation, even to people who just came and watched ours, from other countries like Australia and Canada, they got good compensation just for being there and watching it.

[ends at 0:01:45]

Description

Terry Hilliard was born in 1932 and applied to join the RAF at the age of 15. He was promoted to flying officer after his service during the Suez Crisis in 1956 and then participated in Operation Grapple in 1958 with 76 Squadron. He was assigned to fly through radioactive clouds to collect samples after the bomb detonation. In this remarkable clip he relives the experience of witnessing the blast from the cockpit – trying to keep the plane steady while covering his face with one arm.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Terry Hilliard was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Fiona Bowler. This project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

You can’t describe the flash. It was absolutely incredible, and mine wasn’t the most powerful bomb. But you could literally see the bones in your hand, it was just like looking at an X-ray, it was momentarily. But when it had gone and your arm’s down, your eyes were still seeing these bones, it was retentivity on the retina, and it was, you know, you’re looking into a blackness with this bone in there.

And you’re trying to fly this plane!

And with your arm there, with one hand, at your maximum height where the plane tended to stall or get compressibility, and you were trying to hold, because in those days there was no machinery, no autopilots, no computers, it was all push, pull and rudder and wires going to the elevators and you had to pull them physically and so on. So a bit of electric for little motors, but… And you were trying to hold this thing level and talking to the crew: ‘Are you alright in the back there?’ [laughs] And listen to the radio. And then when they said, you know, the turning point, you had to turn the plane.

[ends at 0:01:15]

Description

Terry Hilliard talks about films of the test sites created by the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE) and how they showed a lack of safety precautions. Hilliard discusses the laidback approach to safety procedures more in other parts of his life story interview. He has a unique perspective as someone who flew planes through radioactive clouds shortly after weapon detonations.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Terry Hilliard was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Fiona Bowler. The project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

In the AWRE film, they show them building the runway and doing this and that, and they mention, we built sixteen radiation-proof dwellings for protection. Who went into those? The Head of Bomber Command, the head officer commanding the base, and the AWRE.

Yeah.

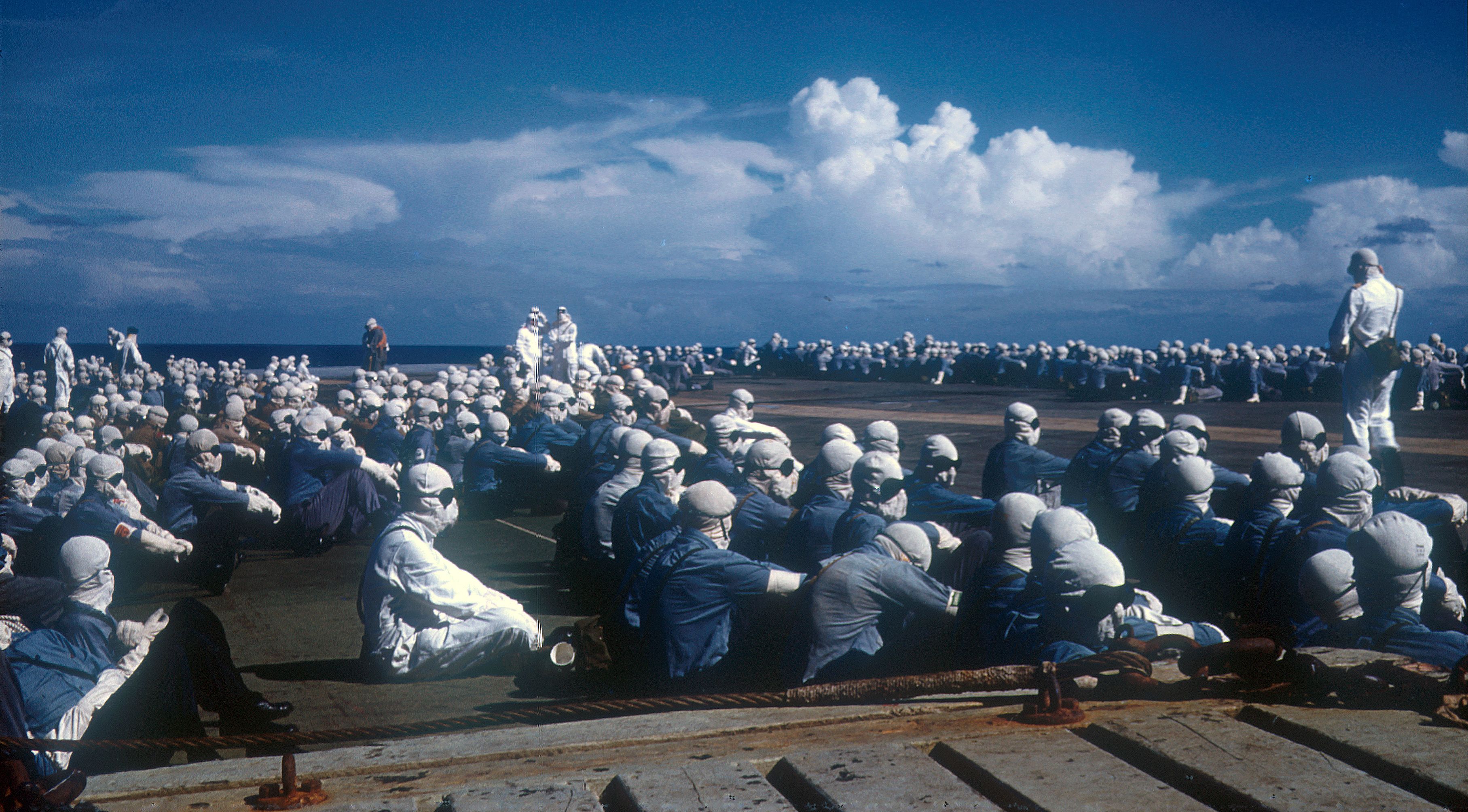

Then they show an airman working eight miles from the explosion picking up the bits with his hand, collecting the debris. Straight after the explosion, just in shorts.

Yeah. Just in shorts.

And that’s in the film.

Yeah, yeah.

And they don’t make anything of it, they didn’t say, ooh dear, you know, he hasn’t got any protection on. They just ignore it. But it’s in the fifties, you know, health and safety wasn’t invented.

[ends at 0:00:58]

Description

Terry Hilliard reflects on the possible health effects of being involved in the nuclear testing programme. Because the test programme was top secret, many veterans remain uncertain about the levels of radiation servicemen were exposed to.

This is a short extract from an in-depth interview. Terry Hilliard was recorded for the Oral History of British Nuclear Test Veterans project in 2024. The interviewer was Fiona Bowler. The project was run in partnership with National Life Stories and the full interview can be accessed at the British Library.

Transcript

Several of the other Grapple people have also, their descendants have given birth to disformed children. So for what it’s worth, I’m not saying it was us, I don’t think it was us, but it could just be another coincidence, I don’t know. But these are the sort of after things you find out now, and we’re talking about, what, sixty, seventy years ago? It’s all been kept, and still it’s secret.

[ends at 0:00:28]