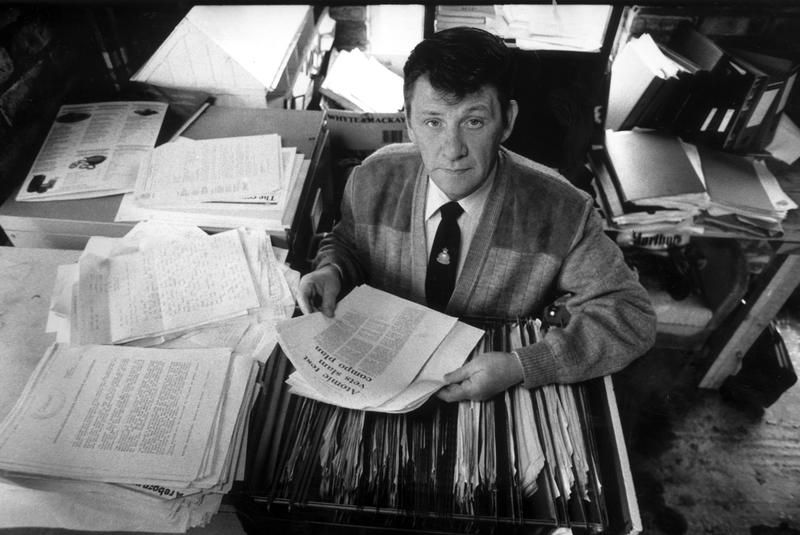

My thoughts on it, my personal – and they are my very personal thoughts – some would agree and some would totally disagree. The fight that we’re having to put up to get recognition, despite – what sort of recognition is irrelevant – but to have to basically crawl on bended knee and beg for a medal, 65 years down the line after the issues, it really… Had they given us a medal and thought, referred to us as heroes, as we are [laughs], of course, you know, within a couple of years or so of all this happening to us, I could have accepted it, I would have been very, very proud, but the fact that we’ve had to beg on bended knees, you know, it, it loses its value to me. And I think one of the reasons for me standing down as vice chair, over and above the medical issues, which were the main reason, was because of those thoughts. And being so involved with the guys that were suffering, as I am, in some cases worse than me, for the British test, and for the American test. It has, I’ve been talking quite a lot about this to my wife and to my doctor, I’m suffering mentally, I think, over all this because I know too much. And the ideas, as I say, of having to wait and have to, you know, beg for a medal. It’s nice to be awarded a medal, but to have to go and beg for it, it loses its value to me.

[ends at 0:01:59]