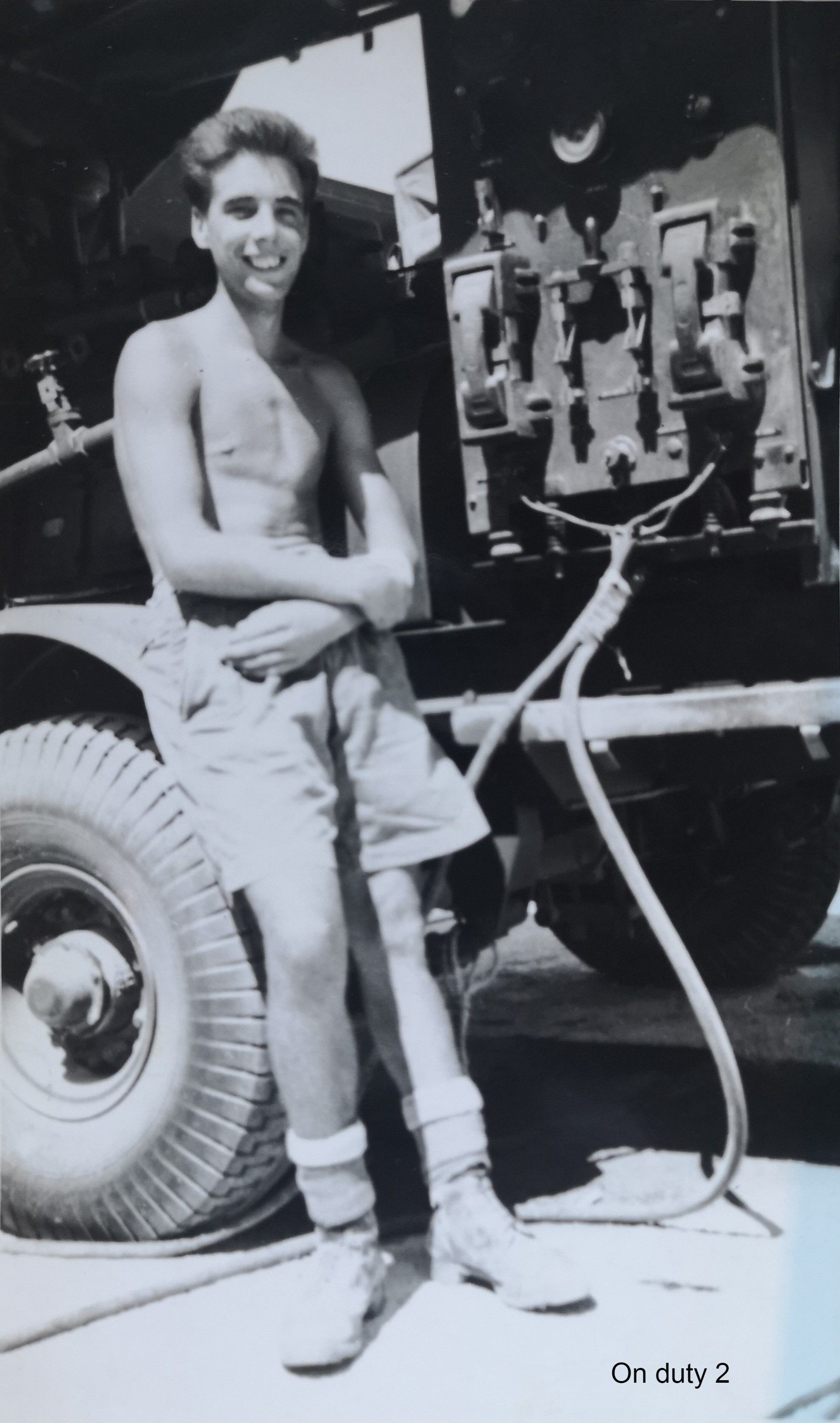

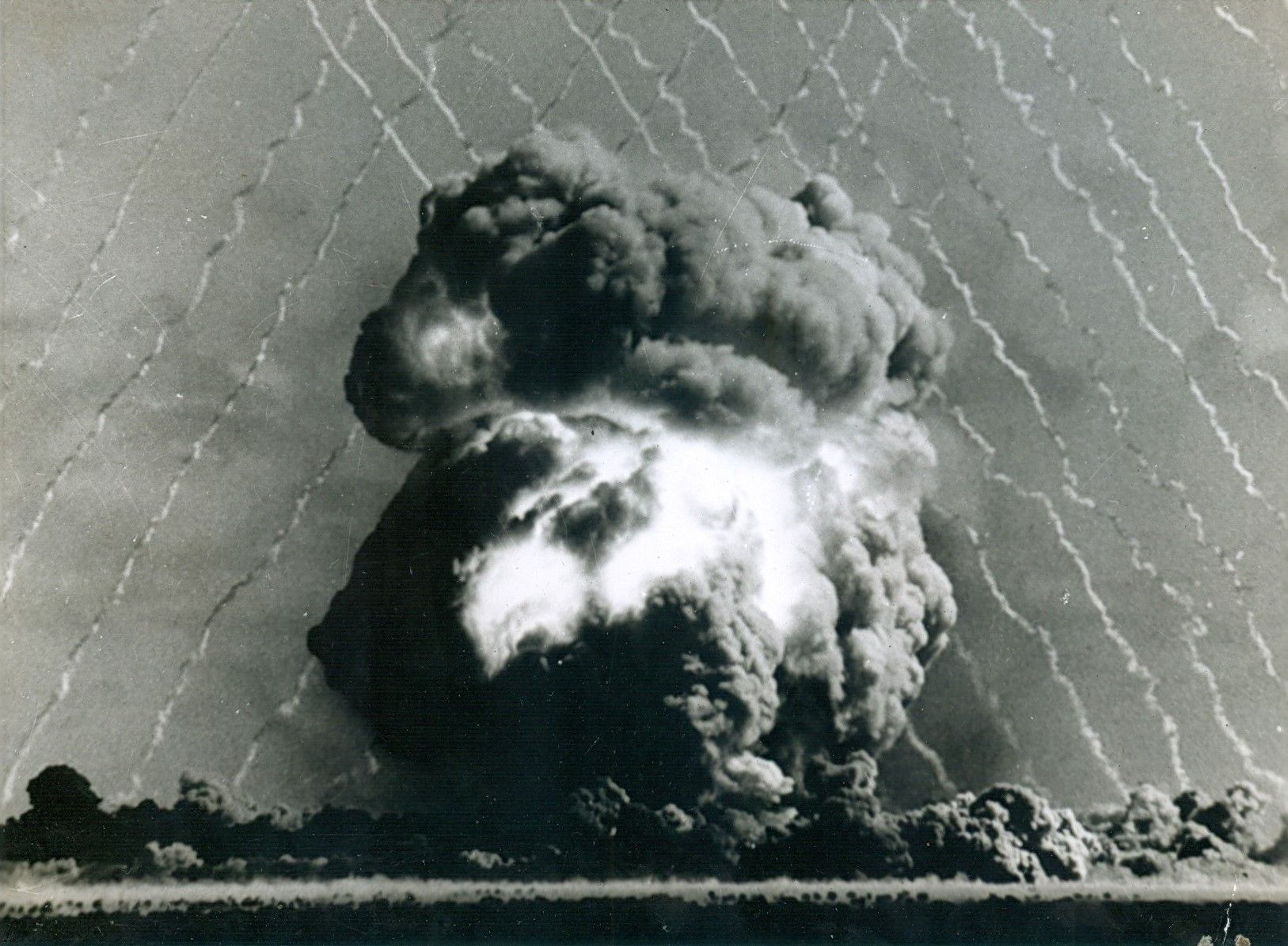

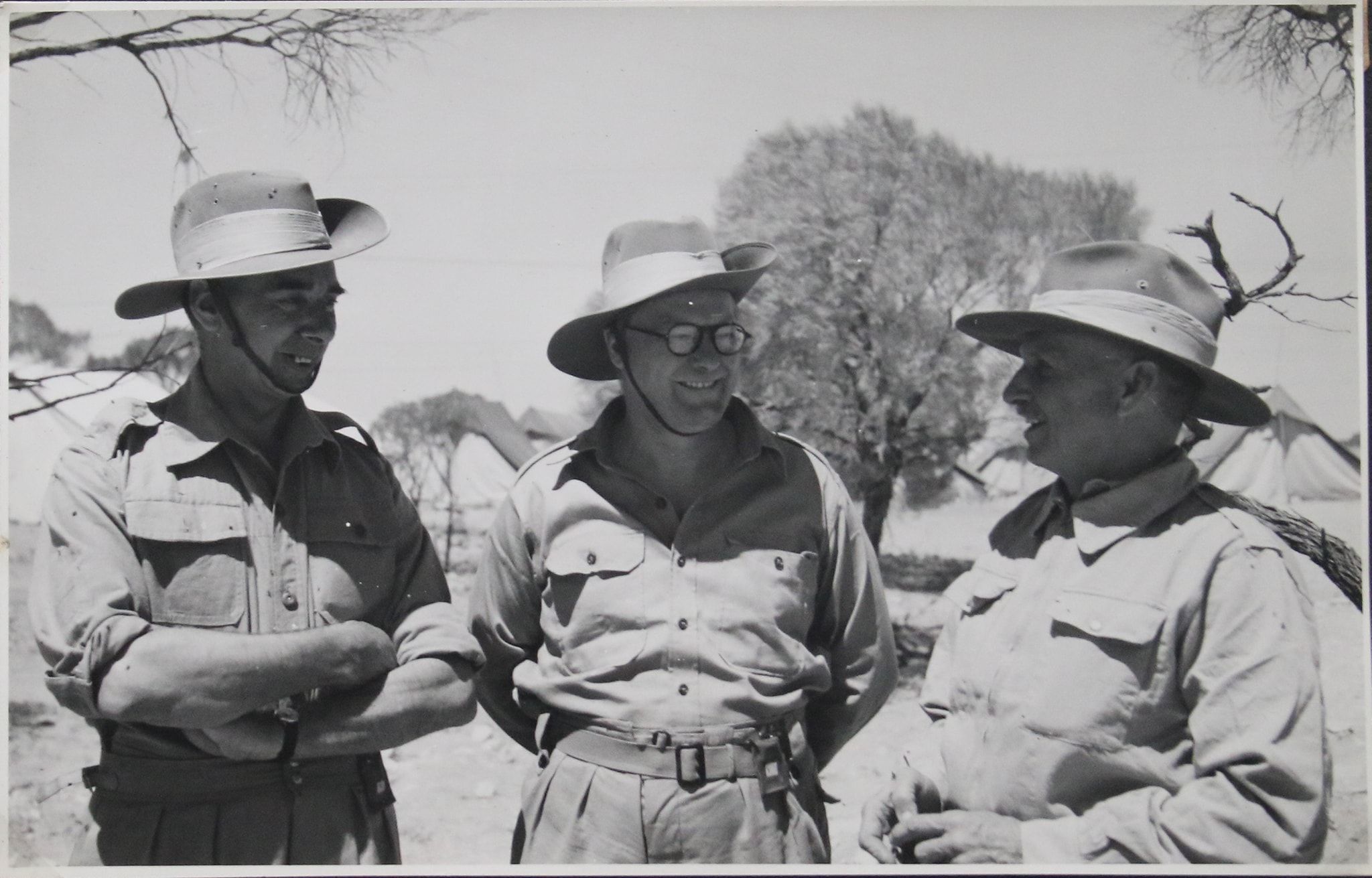

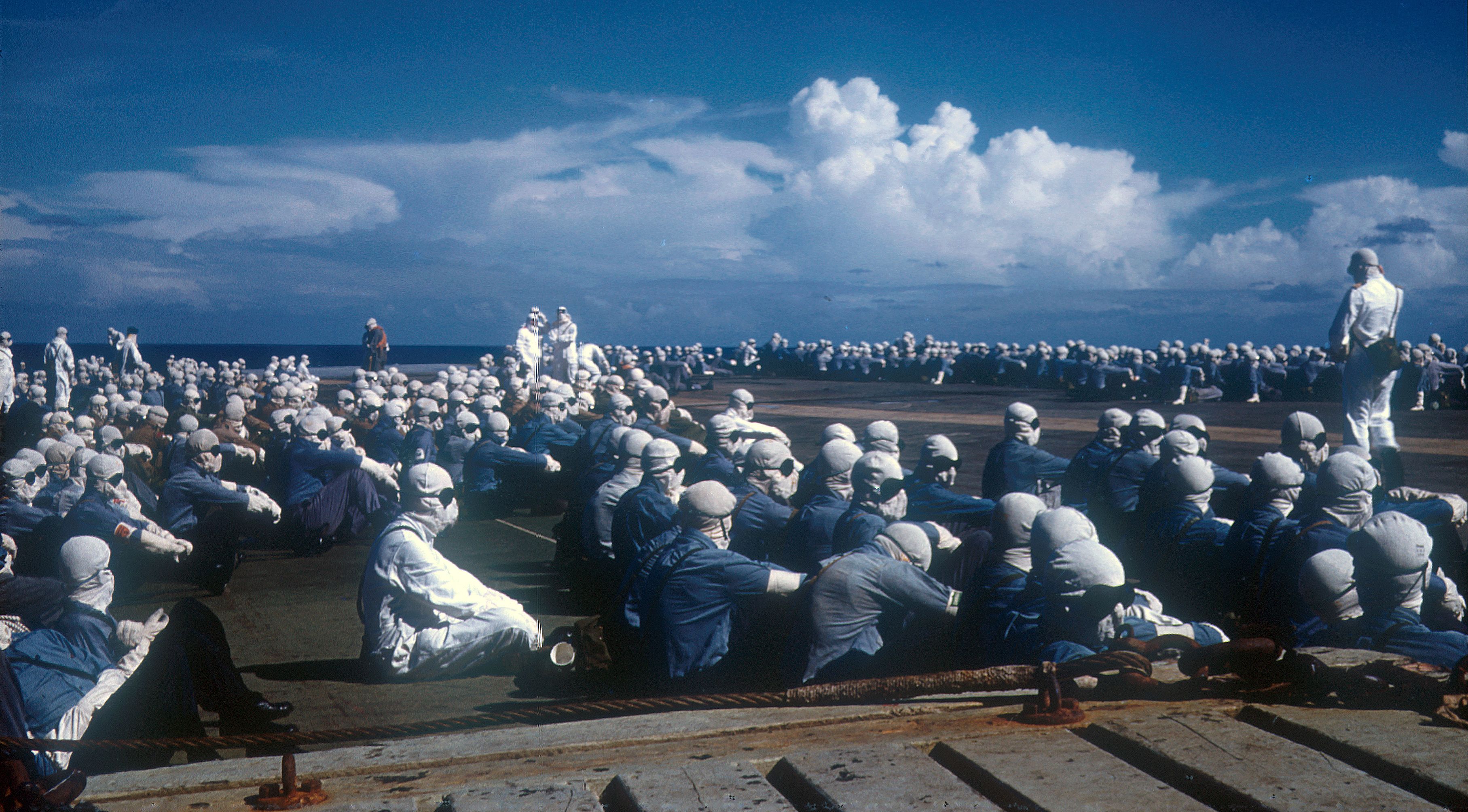

It was an experience that I hadn’t, well, I’ll never, hopefully, never see again really, because it was something new, Britain didn’t really know what the outcome was going to be on the testing of some of these devices, so it was a kind of a, bit of a challenge. I only wish that we had more information about what we had to do, because we weren’t. Someone would say, right, you dig a hole, four foot square, and you dig a hole four foot square, and what’s it for? Oh, some instrument. That’s all we know. And this is what you used to get, just stupid answers. You’re not here to ask questions, you do what we told you to do, and so you can get no further, no one’d commit themselves. The scientists, they didn’t tell you anything. In fact, they hardly ever spoke to you. So, you were doing things by what the army said, or what was really down to whoever was in charge of our lot, to tell us, go and do this, go and do that, and that’s what it happened to be. Every day was the same. You used to get the weekend off, or Sunday, sometimes Saturday, it just depends how they felt. But most of the time, free time, there was nothing to do, I mean they only had the cinema, you couldn’t go there every day, they didn’t want to run a truck all the way down and then run it back for just to, see there, you’d go once or twice a week. But they had a big swimming pool there. But, thinking back, it does come to you now and again, you think back, back of your mind something’s irritating you, and it’s there until you try and get rid of it.

[ends at 0:01:54]