Yeah. During Grapple?

Aye. Grapple Y, aye.

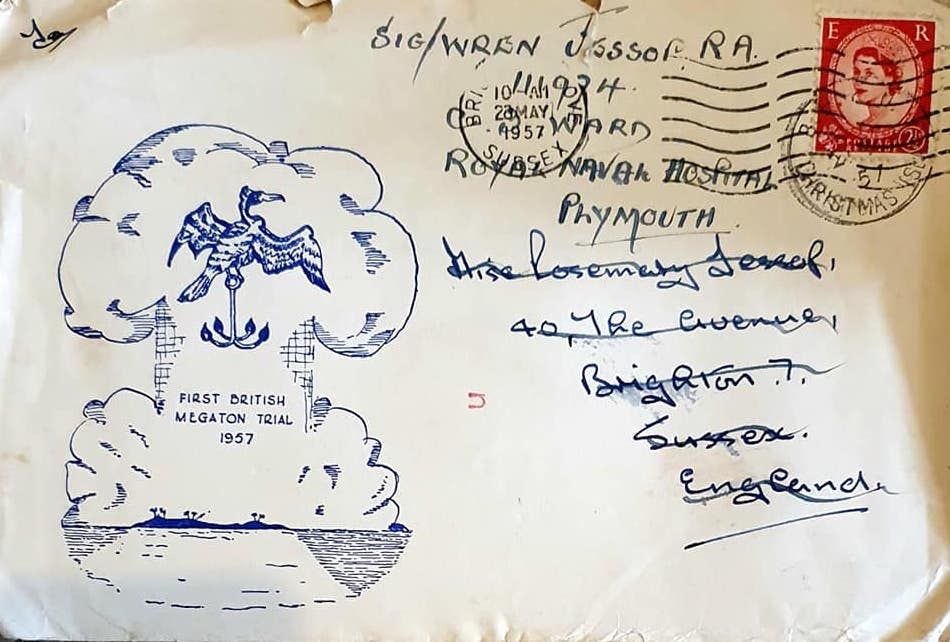

So, I mean it’s all leading up to that first test, because that was Britain’s biggest ever bomb, wasn’t it, Grapple Y?

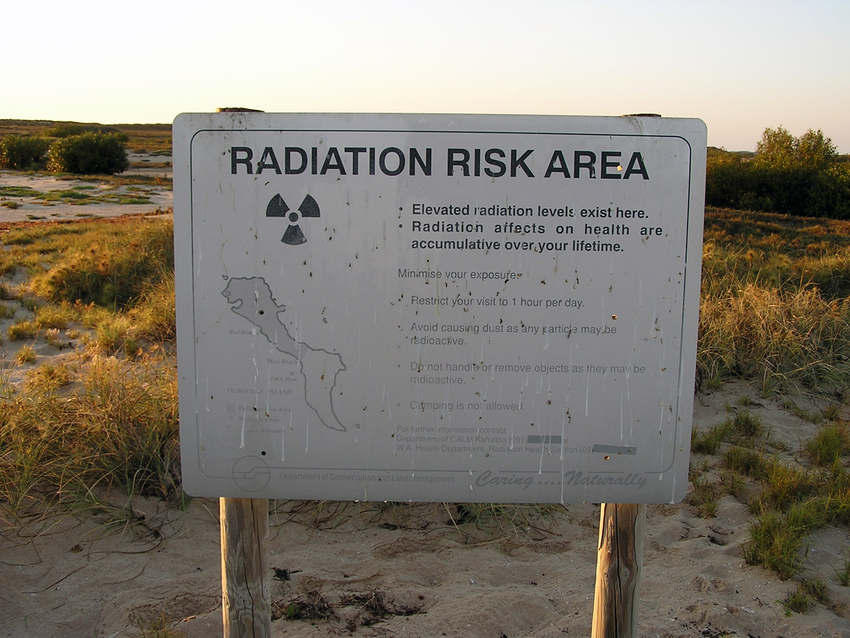

My analysis on it, that I found that the cases of leukaemia, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, were mainly attributable to Port London. It did rain that day, and Alan just sent me a, Alan just brought over new information there about Lord Penney telling you how a nuclear bomb can start a thunderstorm. I’ve got the documents here on it. He just brought me that over yesterday.

There are atmospheric physicists at Reading today are looking at weather formations using historical Met data based on rain patterns coinciding with nuclear tests in the fifties and sixties.

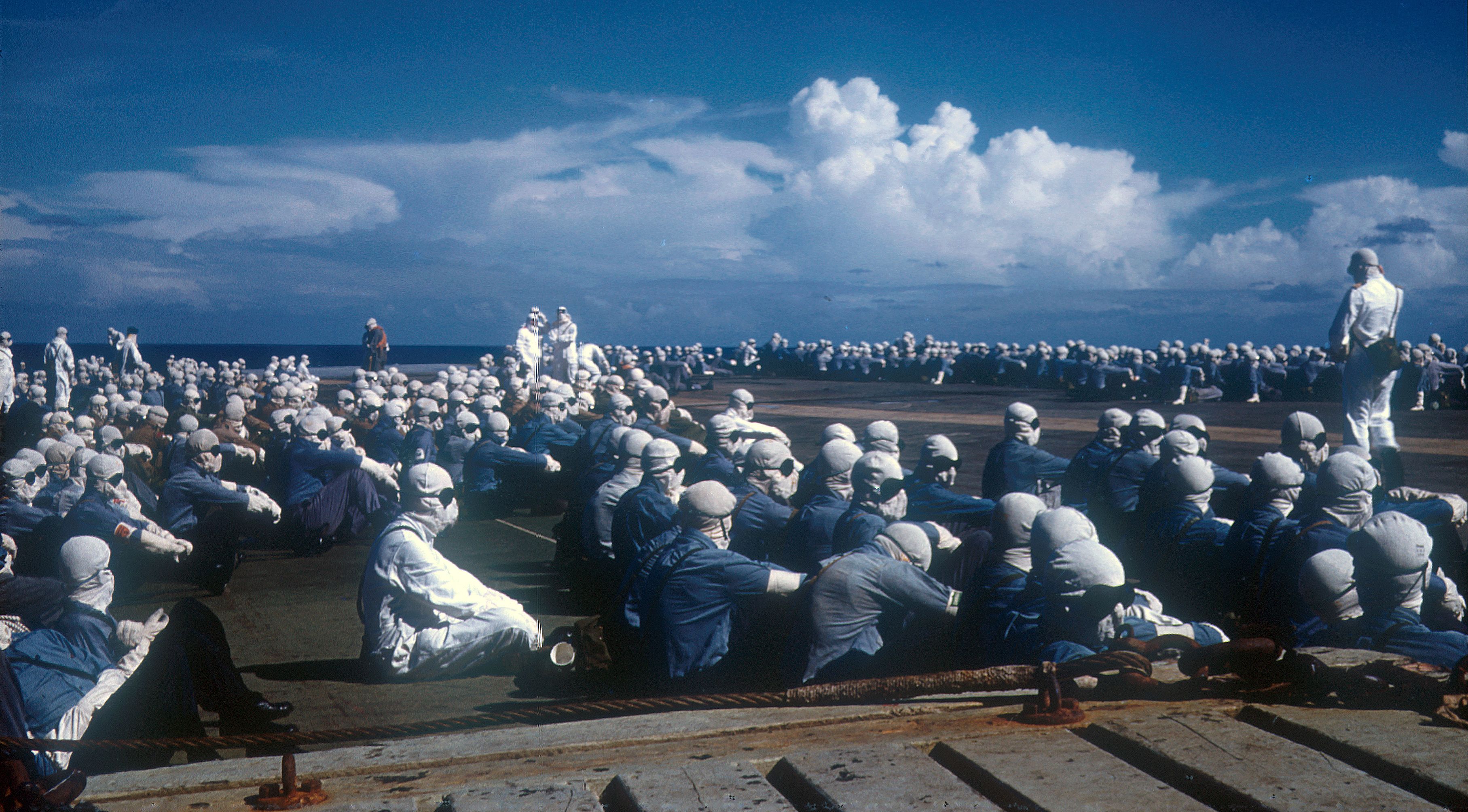

That’s right, yeah. Although they say, the Ministry of Defence have always maintained it never rained. But I’m sorry, you’re liars, for the simple reason being, I was there. I walked back – and another thing, which you’ll never hear from a nuclear veteran – when we were walking back to the tent, I told you there was two men standing at the side with their white, all their whites on, with masks on, goggles on, and they shouted ‘Get under cover, get under cover’, that’s when it started to rain. And it was like… and originally, or initially, it was actually like big droplets, and then it just come down, the rain. We were taking off our whites to throw into a big bundle, they told us, put your white gear in that bundle there, so you just took it off and threw it in a bundle. So we took it off, threw it in a bundle, walked back to the tent. These guys were saying, ‘Get under cover, get under cover’. No way, we were standing in that heat for about three hours and that rain was just lovely and cool, you know. Didnae think, radiation or anything like that, or didn’t even know what radiation was. I don’t how we could have spelt it in those days even. But, walking back down to the tent, we were doing… Alan, myself, Billy Pettigrew, I think it was, we got a can of beer each and sat outside the tent drinking it and just, we never spoke, we just kind of looked at each other. What do you think of that, eh? Don’t know.

And you think, looking back on it, that there were more lymphomas for people in Port London as opposed to main camp?

Yes.

Is that because of the rainout from the test?

I would think it was from the rainout, aye. You see, this is what I was leading up to. After we had our beer, it was just about lunchtime, so we went up to the canteen, we were standing in the queue with our mugs, waiting for our – your knife, fork and spoon in your mug – standing in the queue. And this guy’s coming round with a ladle and a bucket. We said, what the hell’s that he’s putting… it was navy rum. Because we served under HMS Resolution, although the camp commander was Major Hubble, lovely big man. So, oh, we’re getting a tot of rum. I’d never tasted rum before, so drank it. Ugh! Drank it all anyway. Then we had our lunch. Says to the guy that was dishing it out, ‘Why are we getting the rum?’ He says, ‘Because it’s traditional in the navy, every time it rains, we issue rum’. So that would have went on HMS Resolution’s manifest, you know. So, you know, so that night, that night it was, oh, the toilet. You couldnae get into the toilet that night. Stomach, and I says, ‘Should never have drunk that rum’. That nausea feeling I had, and diarrhoea. I didn’t know whether to be sick or have diarrhoea. You’re sitting on a pan, making all kind of funny noises. And at the same time, you’re urgh, like that, you know. So, didnae know what to think. [00:04:58] About two days later, I was in a tent, and I woke up, I couldnae open my eyes, God’s sake. I went out of the tent, to the flagpole, and there was a wee mirror there, and I had kind of water blisters under here, down here, on my neck, and just on my chest. And I’m trying to squeeze them out and that, and I couldnae. They weren’t painful either, you know. So I says, I need to go to the doctor, see what’s wrong here. So I went along to the doctor and there was loads of guys there with blisters and, you know, just various types of skin things and that, you know. And he was putting a solution on us and that was it. But it cleared up after a few days. Left me a bit scarred, right enough. And, never thought anything about it at all.

At what point did you think the fact that we were, the fact that it rained after Grapple Y is problematic for us because it could have exposed us to radioactive fallout, when did that occur to you? Presumably once you were back and years later?

Oh aye, years later, you know. Because we always maintained, everybody that took part in the test say that, quite clearly. Oh, it rained that day just after the test, you know. And yet the Ministry of Defence said there was no rain on Christmas Island that day, you know. What? The bloody water was running down the roads. They’ve got it in film, you know.

Yeah. And that’s what the Dispatches programme was about.

Exactly. So, you know, this is what, so there’s lies, you know. At the Ministry of Defence you’ve got, you had good liars and bad liars, you know? That was the problem, you know.

[ends at 0:07:07]